Matt Haworth, meteorologist for StormGeo, presented research connecting Gulf of Mexico sea surface temperatures to severe weather potential along the Gulf Coast.

“Basically I expanded on a study done by Roger Edwards and Steven Weiss out of the Storm Prediction Center done in 1996,” Haworth said. “I expanded the study to include the areas within 100 miles of the Gulf Coast.”

Haworth found that there was an increase in severe weather when the Gulf of Mexico sea surface temperature was higher.

“During the warm cases, we had over 110 out of the 202 cases (of severe weather) I found,” Holworth said.

The idea is that an small increase in sea surface temperature could mean extra moisture available in the atmosphere. And, as echoed by Holworth’s colleagues in other presentations, an increase in dewpoint means more CAPE (instability) – regardless of the amount of instability available from daytime heating.

Math says: An increase in moisture can increase CAPE. Don’t just need sunshine! #NWAS17 pic.twitter.com/9p61Ew78e2

— Nick Lilja (@NickLilja) September 20, 2017

Holworth looked at an area within 100 miles of the Gulf Coast along the I-10 corridor from San Antonio to the Florida panhandle. He limited his study to between the years of 2000 to 2016.

The verdict: The warmer the water, the better the chance for tornadoes and wind in the data collected. The colder the water, the better the chance for hail in the data collected.

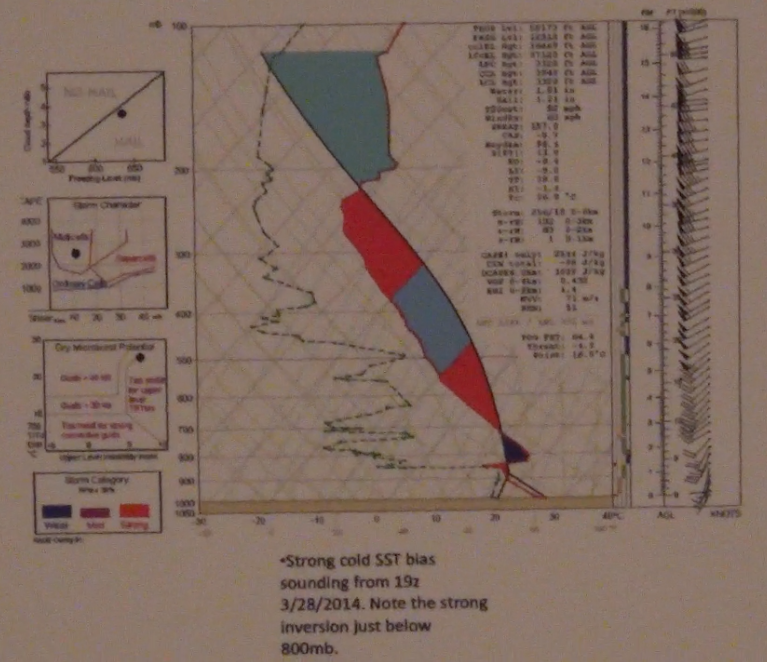

Holworth hypothesized that the difference between warmer and colder events’ severe weather may be linked to the interaction with the mid-levels of the atmosphere.

“In the hail growth zone, there is quite a substantial amount of CAPE there,” Haworth said. “That pops out as an initial observation.”

Haworth did mention this was going to be an area of further study, citing steeper mid-level lapse rates and dry air as other possible reasons for more hail when the Gulf of Mexico waters were cooler.

“Or this might just be an anomaly,” Haworth said. “There may not be a correlation at all.”

Haworth mentioned that the sea surface temperature doesn’t need to be established in order to effect the weather.

“We don’t need a very long term period,” he said. “We just need a week to three-to-four days leading up to the event.”