As we get toward the end of a long – and I mean LONG – Atlantic Hurricane Season, I wanted to pause for a moment and reflect on the trend we are seeing in the Tropics and how was we experienced this year is becoming, in a way, more likely.

How likely is “more likely” in this case?

Well, the chances are still low, but they aren’t zero. And they are higher in 2020 than the chances were in 2000. And much higher than the chances were in 1970.

The global climate is changing

I know some people are still skeptical that our climate is changing. Others are skeptical that humans are causing that change. I totally get that. But it is worth noting that something like 99-percent of the people who look at this stuff for a living think it is happening. And more than 95-percent think humans are the cause.

Imagine talking to 95 doctors and they all look at you and say, “you’re going bald.” but then five other doctors just say, “Actually, this is a normal pattern, and your hair will grow back.”

Who are you going to trust? The 95 doctors that agree you are balding. Or the five who say, no worries?

And while balding may not kill you or harm you directly, it may cost you money to fix or cover up. Or you may just say, I’m balding big deal. And wear it as a badge of honor. No reason to change your ways, if this is how it is supposed to be, this is how it is supposed to be, you say!

While that works for hair on your head, for the global climate such a pioneer approach isn’t advantageous to human survival.

The quick and simple physics and chemistry of a changing climate

We’ve all walked out into a parking lot to our car, in the dead of Summer, and opened up the door to get blasted with a ‘whoosh’ of much hotter air. This is because the air inside of the car is getting heated up with nowhere to go. In science we call this a “Closed System” since air can’t get in or out – but the Sun’s energy can. But not all of the energy. Because the windows are on the side of the car, but not the top, the energy gets in and then gets trapped by the roof. It is the reason so many advocacy groups say to “check the back seat” and “never leave kids alone in a car” in the Summer. That kind of heat can be deadly.

On a 85-degree day, the inside of a car can reach over 110 degrees in as little as 20 minutes.

A very similar thing is happening to our planet. The vast majority of all of the mass on our planet is stuck on the surface or in the atmosphere, while the Sun’s energy is allowed to penetrate that system. It can come and go as it pleases. As the world turns – no, not the Soap Opera – each spot collects or dismisses energy from the Sun. When your spot on the Earth is toward the Sun, you collect energy. And when your spot on Earth is facing away from the Sun, you dismiss energy.

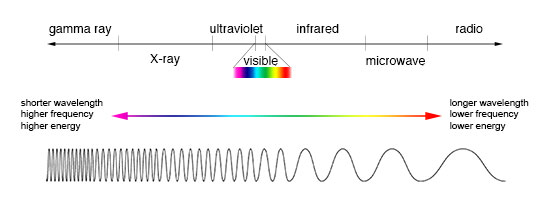

Often the energy collected is “shortwave” energy from the Sun and the energy dismissed is “longwave” energy that is radiated out by objects releaseing heat at night.

The distinction between the two is where the energy falls along the electromagnetic spectrum. short-wave wavelengths carry more energy than long-wave wavelengths. This is why, for example, gamma rays are dangerous and radio waves are not.

And over billions and billions of years the Earth came to a nice equilibrium. Sure there were ups and downs, but those ups and downs occurred gradually over thousands and millions of years.

That equilibrium – and all of the slow ups and downs – was largely dependent on the different masses in the atmosphere.

I know a lot of times we don’t think of the atmosphere as having “mass” since we see clouds floating around, planes flying, and birds gliding. But the mass, and thus the chemistry, of the atmosphere has been very important over time.

This is because different molecules have different chemical and physical properties – including how each reacts differently to different kinds of energy.

It turns out that things molecules like, as a for instance, Carbon Dioxide, absorb longwave energy (longwave radiation). So the more CO2 there is in the atmosphere, the more longwave energy gets trapped in the atmosphere. And that is energy that, in years past, would be escaping out into outer space. But instead it is trapped.

Sound familiar?

It sounds a bit like our Car Example above. The Sun’s energy gets in, but it can’t get back out.

The consequences

Warmer overnight temperatures is a ‘low hanging fruit’ when looking for an example of this absorption of longwave energy (longwave radiation). But there is another consequence. This one is a bit more dire, but not the End of the World: There ends up being more energy in the atmosphere.

And you might say, “So what?” and that is fair.

Other examples of energy floating around would be TV and radio waves. Those are moving through the atmosphere all the times. That is energy, too. But the difference is that the energy of TV and radio waves just passes right through the atmosphere. None of it is absorbed. The longwave energy we are talking about it absorbed.

An astrophysicist, Charles Liu, recently said that “adding a degree to the atmosphere was like adding the energy of 100 million nuclear bombs.”

And that energy is just sitting there waiting to be tapped. Because energy cannot be created or destroyed – it can only be changed.

Think back to watching a weathercast (by me or anyone else) and often times the meteorologist on-air is referencing atmospheric energy when talking about a potent storm system. That energy can come from many places (surface heating, atmospheric mixing, etc) but when the atmosphere has easier access to more of that energy, stronger storm systems are easier to make.

New research: Hurricanes are getting stronger, faster

It doesn’t take a meteorologist to see that hurricanes during the past few years have repeatedly undergone Rapid Intensification. In fact, during the past few years it seems like it is happening more often.

So, researchers are looking into if this is actually true. And if so, why. It is still early in the research, the numbers show that this is happening more frequently.

And so far in 2020, there have been nine tropical systems that have went through Rapid Intensification.

The trend line on this shows that the atmosphere produces one extra rapidly intensifying storm today than it did back in 1950. Today the trend line shows an average of 4.4 RI hurricanes where it was about 3.4 in 1950.

That said, since 2010 the average number of RI hurricanes is 4.72. Three of those years (2010, 2017, 2020) have featured more than eight RI hurricanes.

That also means the proportion of RI hurricanes is increasing.

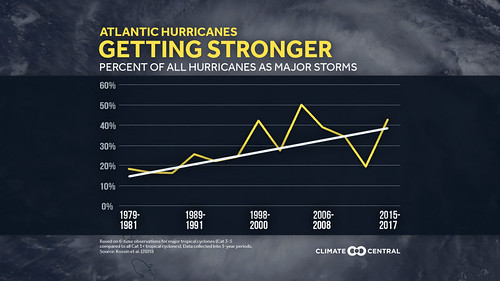

So, the chances that any one hurricane that develops, develops into a Major Hurricane is going up. And this lines up with what research from 2016 found.

This isn’t just due to the lingering energy in the atmosphere, though. It also has to do with water temperatures.

As more heat remains in the atmosphere, that warms the ocean waters, too. This happens because the water and the atmosphere, near the surface, also have to stay in equilibrium. So the warmer one is, the warmer the other gets. Not only at the surface, but also at depth.

As storm systems churn up the water and freshwater mixes with saltwater (runoff/precipitation), this ‘turns over’ the ocean waters. The cooler dense water moves to the surface as the warmer less dense water cools and sinks. This is a natural process that is speeding up in some places.

As noted by the image above, in the Gulf of Mexico.

This creates a – generally – warmer water basin. And a generally warmer basin is capable of producing stronger and more robust tropical systems.

Ollie Williams was right

Weather Rain GIF from Weather GIFs

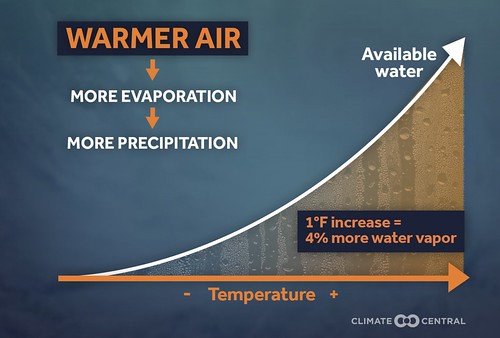

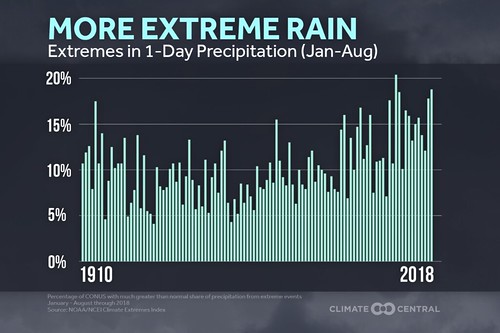

The more heat in the atmosphere, the more water vapor that will be suspended in the atmosphere.

And the more water vapor in the atmosphere, the more rain that can fall at any given time.

That means that inland flooding from landfalling tropical systems may increase, too. So while the potential intensity for any given hurricane is increasing, so too is the potential rainfall and flooding threat.

The Bottom Line

I know what you’re thinking: “This sounds awful, Nick.“

And, yeah, I can’t disagree. The evidence is not encouraging. While Hurricane Seasons like the one we are experiencing in 2020 are not “likely” to happen, seasons like the 2020 Atlantic Hurricane Season are becoming more likely given the change in our climate. And humans have a direct impact on that change.

The good news is that because we have a direct impact on the change, we can do things to change the outcome.

This is why so many scientists push for people to reduce each person’s ‘carbon footprint’ now. It can be done by little steps, too, it doesn’t have to be anything drastic. Drive less, recycle more, stop using one-use plastic bags, run the AC/Heater a few degrees higher/lower than you currently run them, and plant some trees… those are all great starts.

Want to go further? You could drive a more fuel efficient car, like a hybrid. You can encourage lawmakers to fund proper forest management to reduce wildfires. You can make sure your home is using adequate insulation – and if not, buy more, upgrade your windows and doors, replacing the siding or buy a new light-colored roof.

You would be amazed at how far those little steps can go.

A quick note…

I’m sure you’ve heard people say, “First it was global warming, then global cooling, then global warming, now climate change… these people don’t know what they are talking about.”

Except they do.

The problem – a lot like with COVID-19 – was not the research or the scientists. It was the people tasked with communicating that research to others as well as people’s baseline understanding about what was being communicated.

Remember when the rumors that “COVID doesn’t like the heat” started circulating. I think even the President mentioned that at one point. News organizations then started reporting it.

The problem was that the actual research that was being done wasn’t making a prediction about if COVID did or did not like heat. It was simply trying to get an idea of any commonalities between the outbreaks at that time. and one commonality was the climates were all cooler.

But it didn’t mention anything about if COVID did or did not like / spread faster or slower in the heat

Global cooling was never a real theory. It was a hypothesis that was eventually dismissed within the scientific community. But because it made traction in the global news media, people took it was fact.

When, in fact, in the mid 1970s the World Meteorological Society was busy warning of a continued trend of global warming.

The reason scientists choose to call it Climate Change now instead of Global Warming, is due to the baseline understanding and knee-jerk reaction from most people when they hear the term. And there is still a residue of this evident in casual conversation every time it snows. Someone invariably says, “Snow? So much for Global Warming.”

While tongue-in-cheek, it is important to note that even if the globe is warmer, it can still snow. It isn’t called “Global Melting” afterall.

So instead of trying to have that discussion with people every time something cold-related happened, there was an effort to be more clear with the results of what was happening. While the globe is warming, the climate is changing.