A La Nina Advisory is still in effect, issued by the Climate Prediction Center. This is an indication that La Nina conditions have been observed and are forecast to continue.

Recall that a La Nina, in short, means cooler surface water off the coast of Peru.

As you can see from the sea-surface temperature anomalies above, there is cooler water off the coast of Peru.

So, like, what is a La Nina?

Right. It actually does have some hard numbers to it, it isn’t just some abstract ‘cooler’ or ‘warmer’ measurement. La Nina occurs when the sea-surface temperatures are lower than 0.5 degree below average. The atmosphere – globally! – responds to this change. The cooler water temperatures moves the jet stream to different areas and increases the chances that different weather to happen in different areas.

The textbook definition of La Nina from NOAA sounds like this:

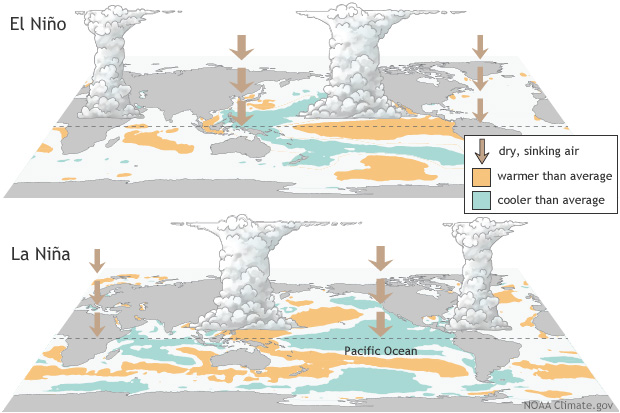

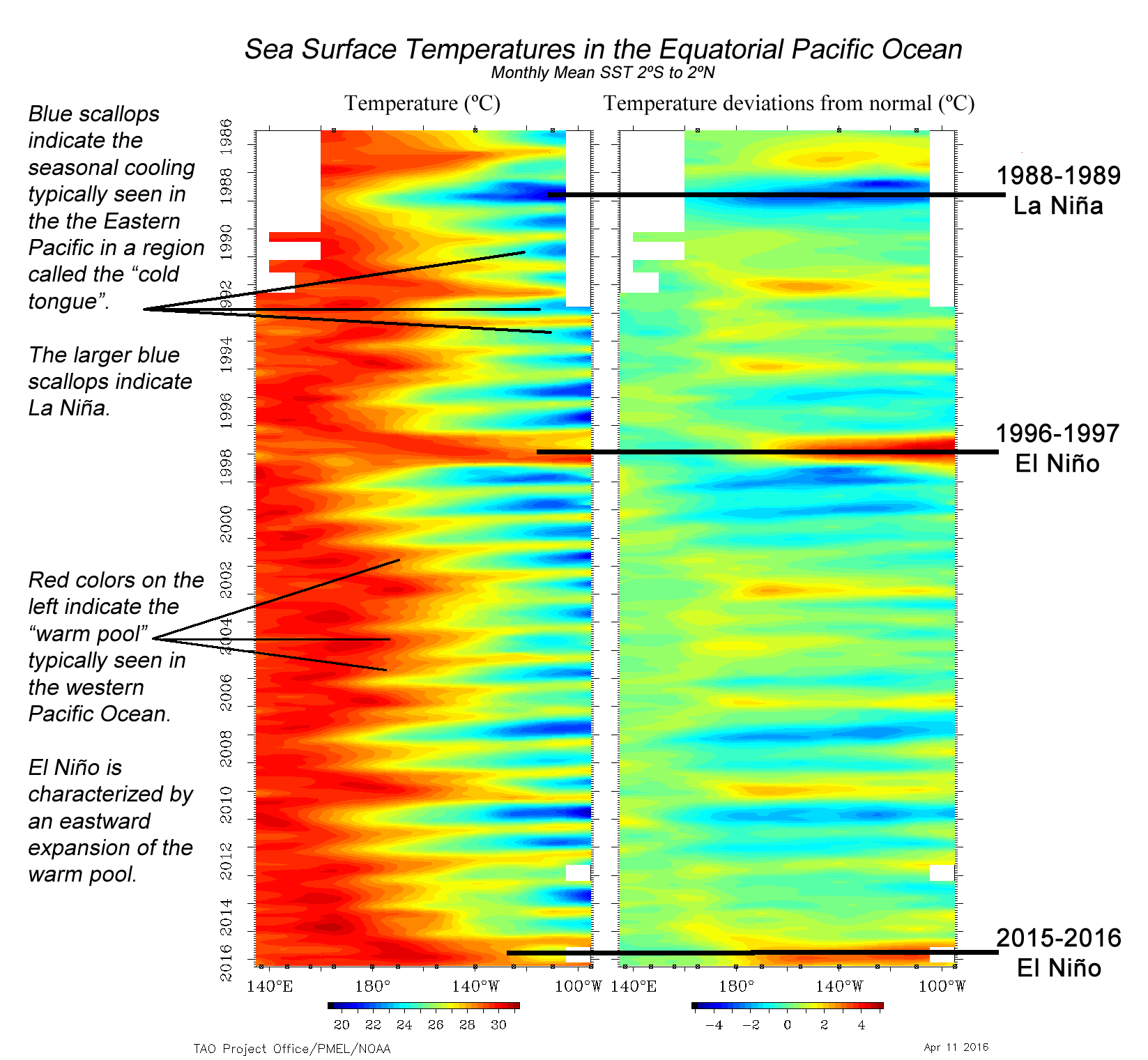

La Niña is characterized by unusually cold ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific, compared to El Niño, which is characterized by unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific. The graphic below shows the sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific (20ºN-20ºS, 100ºE-60ºW) from Indonesia on the left to central America on the right.

Historically, the ocean goes back and forth between El Nino and La Nina. That back-and-forth action is called ENSO by scientists. It stands for El Nino Southern Oscillation. Sometimes we are in an El Nino (more warmer water) and other times we are in a La Nina (more cooler water).

The reason one develops instead of the other is – quite – complicated so hang on tight, we are about to get nerdy…

ENSO is the result of the interaction between the surface layers of the ocean and the immediate atmosphere above it in the tropical Pacific. The internal dynamics of that relationship (the coupled ocean-atmosphere system) involving unstable air-sea interaction and planetary-scale oceanic waves determines which one, El Nino or La Nina, happen. Because the interaction is locally based, but results in global changes, forecasting the development or termination of either El Nino or La Nina is both very difficult and important.

The reason ENSO changes what the atmosphere does, and not the other way around is because this change in water temperature is not seasonally dependent. It isn’t like lake or river temperatures where it is cooler in the winter and warmer in the summer.

What is the forecast?

The forecast is that La Nina will persist through this summer.

From NOAA:

La Niña is favored to continue into the Northern Hemisphere summer (53% chance during June-August 2022), with a 40-50% chance of La Niña or ENSO-neutral thereafter. Below-average sea surface temperatures (SSTs) strengthened during February 2022 across the central and east-central tropical Pacific, with negative anomalies stretching from the central to eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean. In particular, the weekly Niño-3.4 index decreased from -0.6°C at the beginning of February to -1.1°C in the last week, while the other Niño SST regions were between -0.6°C and -1.3°C in the last week.

Subsurface temperatures anomalies (averaged between 180°-100°W and 0-300m depth) were near zero, as the recent warming associated with the downwelling Kelvin wave has attenuated. Below-average temperatures have expanded near the surface and at depth near ~150°W. Tropical atmospheric anomalies strengthened during the past month, with the extension of enhanced low-level easterly winds across the equatorial Pacific and upper-level westerly wind anomalies remaining over the east-central and eastern Pacific Ocean.

Suppressed convection strengthened around the Date Line, while convection was enhanced near Indonesia. Overall, the coupled ocean-atmosphere system reflected the continuation of La Niña. The IRI/CPC plume average for the Niño-3.4 SST index continues to forecast a transition to ENSO-neutral during the Northern Hemisphere spring.

This month, the forecaster consensus favors a slower decay of La Niña due to the recent renewal of ocean-atmosphere coupling, which contributed to cooler near-term forecasts from several state-of-the-art climate models.

For the summer and beyond, there is large uncertainty in the state of ENSO; however forecasters lean toward negative Niño-3.4 index values even if the index does not reach La Niña thresholds. In summary, La Niña is favored to continue into the Northern Hemisphere summer (53% chance during June-August 2022), with a 40-50% chance of La Niña or ENSO-neutral thereafter; click CPC/IRI consensus forecast for the chances in each 3-month period).

Nick, what does that mean for me?

Generally a La Nina promotes the development of severe weather across the Pine Belt – and Southeast – in the Spring. According to research by Mark Bove, “The Ohio River Valley and Deep South see a region of statistically significant increased tornadic activity during La Niña.”

The graphic above shows the difference between an . ENSO-neutral year (normal) and a La Nina year (colder water). It is broken down by three-month intervals: (a) January-February-March, (b) February-March-April, (c) March-April-May, (d) April-May-June.

Notice the red blocks near us for (a), (b) but then those areas lift to our north by (c) and (d). So, despite the “generally drier than normal’ tendencies with La Nina, statistically, there is a section of the severe season that gives the Pine Belt more chances for storms, and thus, tornadoes.

That is between January and April.

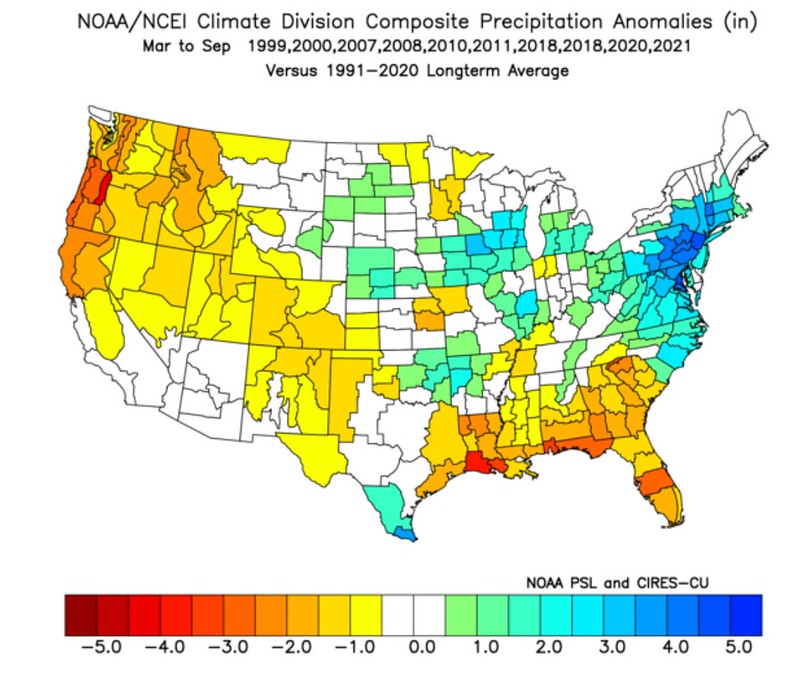

Looking at March through September, La Nina years look to be a bit warmer and drier since 2000.

While that does, technically, include landfalling hurricanes, it also important to note that La Nina summers tend to increase the potential for tropical development, too.

This graphics from the NWS in Jackson, Mississippi explains it pretty easily:

The NWS Jackson writes, “During La Niña, westerly winds high in the atmosphere weaken. This results in an expanded area of low vertical wind shear, allowing more Atlantic hurricanes to develop during La Niña events. La Niña increases the number of hurricanes that develop and allows stronger hurricanes to form. The chances for the continental U.S. and the Caribbean Islands to experience a hurricane increase substantially during La Niña and decrease during El Niño.”

Holy moly! This sounds awful!

Well, keep in mind that just like hurricanes and tornadoes – every La Nina is different. Not every one is full of doom and gloom. The most recent La Nina spring/summer was just last year! So think back. Way back! To 12 months ago. The 2021 La Nina featured an active, but not record-breaking Severe Weather Season followed up by an active, but not record-breaking, Hurricane Season. But with this being the second La Nina Spring/Summer it may lean toward looking like 2011, 2008 or 2000. All were active with severe weather, but not crazy Hurricane Seasons.

Seasonal outlooks like this, though, aren’t often able to give an apples-to-apples comparison.

But knowing if a season features a La Nina or El Nino can be the start of figuring out – in general – what to expect from Mother Nature over the course of a few months.