While the spread of COVID-19 seems to be nearly out of control in some places, in others things are starting to get back to normal. In Mississippi, like a handful of other places in the South, the viral spread is leaning more toward being “out of control” than “completely under control” at this time.

So far in July, there have been a total of 575 COVID-19 related deaths in Mississippi. The data from July 31st is still being tallied. And there is still a chance more deaths may be added via delayed death certificates.

Based on the latest available data from the CDC about causes of death in Mississippi (2017), that means COVID-19 killed more people in a month than the average number of people who die from…

Accidents (145 on average per month)

Stroke (144 on average per month)

Diabetes (97 on average per month)

Flu (65 on average per month)

… combined. With enough room left over to add in…

Firearm deaths (53 on average per month)

Homicide (30 on average per month)

Drug overdoses (30 on average per month)

… and there are still 9 more deaths in the month of July from COVID than all of those combined.

Here is a look at some of the new numbers, new research, and some tips from the CDC to keep you safe.

New Numbers

Here, in two week increments, are the number of cases and deaths in Mississippi dating back to March:

| Two week increments | Total Cases | Cases Per day | Total Deaths | Death rate |

| March 11 – 24 | 380 | 27.14 | 3 | 0.79% |

| March 25 – April 5 | 1630 | 116.43 | 62 | 3.80% |

| April 6 – 19 | 2774 | 198.14 | 118 | 4.25% |

| April 20 – May 3 | 3365 | 240.36 | 141 | 4.19% |

| May 4 – 17 | 3555 | 253.93 | 218 | 6.13% |

| May 18 – 31 | 4320 | 308.57 | 212 | 4.91% |

| June 1 – 14 | 4047 | 289.07 | 156 | 3.85% |

| June 15 – 28 | 7149 | 510.64 | 149 | 2.08% |

| June 29 – Jul 12 | 10116 | 722.57 | 192 | 1.90% |

| Jul 13 – July 26 | 16277 | 1162.64 | 254 | 1.56% |

| July 27 – Aug 9 | 5790 | 413.57 | 162 | 2.80% |

And how that looks graphically:

And graphically with some extra information:

For a larger look at this graph, click here

New Research

Kids camp in Georgia

The CDC released a survey titled, “SARS-CoV-2 Transmission and Infection Among Attendees of an Overnight Camp — Georgia, June 2020” that was conducted by the Georgia Department of Public Health after a kids camp produced an “outbreak” of COVID cases. At the camp, the staff were required to wear masks, but the children were not. This was an overnight camp, where kids slept in the same cabins.

A total of 597 Georgia residents attended camp A. Median camper age was 12 years (range = 6–19 years), and 53% (182 of 346) were female. The median age of staff members and trainees was 17 years (range = 14–59 years), and 59% (148 of 251) were female.

Test results were available for 344 (58%) attendees; among these, 260 (76%) were positive. The overall attack rate was 44% (260 of 597), 51% among those aged 6–10 years, 44% among those aged 11–17 years, and 33% among those aged 18–21 years (Table). Attack rates increased with increasing length of time spent at the camp, with staff members having the highest attack rate (56%). During June 21–27, occupancy of the 31 cabins averaged 15 persons per cabin (range = 1–26); median cabin attack rate was 50% (range = 22%–70%) among 28 cabins that had one or more cases.

Among 136 cases with available symptom data, 36 (26%) patients reported no symptoms; among 100 (74%) who reported symptoms, those most commonly reported were subjective or documented fever (65%), headache (61%), and sore throat (46%).

Unpacking that long paragraph, here are the quick ‘take home’ points:

There were 597 people in total, 344 were tested

Of those tested, the rate of positive tests: 76-percent

Comparing total number of people to positive test results…

6y – 10y – 51-percent

11y – 17y – 44-percent

18y – 21y – 33-percent

All age groups – No reported deaths

This survey lends credence to the hypothesis that while children don’t produce the same – if any – symptoms as adults, that children can still be easily infected by the virus. It also lends credence to the hypothesis that the virus affects children differently with a lower death rate.

According to the authors, the findings in this report are subject to at least three limitations.

1. Attack rates presented are “likely an underestimate” due to the people who went untested or whose test results were not reported

2. Some cases might have resulted from transmission occurring before or after camp attendance

3. Knowing if people followed COVID-19 prevention measures at the camp is not possible (physical distancing, use of cloth masks, etc)

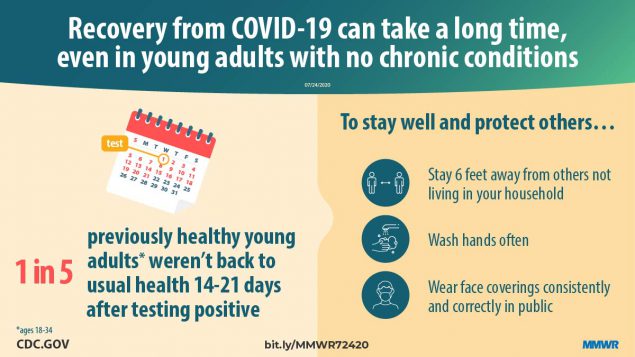

Just because you recover, doesn’t mean it happens quickly

The CDC published another report, titled “Symptom Duration and Risk Factors for Delayed Return to Usual Health Among Outpatients with COVID-19 in a Multistate Health Care Systems Network — United States, March–June 2020” that collected 270 people to survey them about how they felt two to three weeks after testing positive for COVID-19. These people were those who are classified as “mild” cases, where hospitalization was not necessary.

This is not a “large” sample, but may give insight into how some people may respond to an infection.

The authors wrote:

Among 292 respondents, 94% (274) reported experiencing one or more symptoms at the time of testing; 35% of these symptomatic respondents reported not having returned to their usual state of health by the date of the interview (median = 16 days from testing date), including 26% among those aged 18–34 years, 32% among those aged 35–49 years, and 47% among those aged ≥50 years. Among respondents reporting cough, fatigue, or shortness of breath at the time of testing, 43%, 35%, and 29%, respectively, continued to experience these symptoms at the time of the interview.

These findings indicate that COVID-19 can result in prolonged illness even among persons with milder outpatient illness, including young adults. Effective public health messaging targeting these groups is warranted. Preventative measures, including social distancing, frequent handwashing, and the consistent and correct use of face coverings in public, should be strongly encouraged to slow the spread of SARS-CoV-2.

Reasons for the lingering health issues is unknown at this time, as this report was not tasked with answering that question. Previous reports indicated that viral load from COVID-19 may linger in the body for up to (and beyond) 14 days after a fever subsides. So more study may be needed at the intersection of these two pieces of information.

The authors noted that the symptoms that were most likely to remain, even after the illness had ‘run its course’ were cough, fatigue and shortness of breath.

From the authors:

Most studies to date have focused on symptoms duration and clinical outcomes in adults hospitalized with severe COVID-19 (1,2). This report indicates that even among symptomatic adults tested in outpatient settings, it might take weeks for resolution of symptoms and return to usual health. Not returning to usual health within 2–3 weeks of testing was reported by approximately one third of respondents.

Even among young adults aged 18–34 years with no chronic medical conditions, nearly one in five reported that they had not returned to their usual state of health 14–21 days after testing. In contrast, over 90% of outpatients with influenza recover within approximately 2 weeks of having a positive test result (7). Older age and presence of multiple chronic medical conditions have previously been associated with illness severity among adults hospitalized with COVID-19 (8,9); in this study, both were also associated with prolonged illness in an outpatient population.

Whereas previous studies have found race/ethnicity to be a risk factor for severe COVID-19 illness (10), this study of patients whose illness was diagnosed in an outpatient setting did not find an association between race/ethnicity and return to usual health although the modest number of respondents might have limited our ability to detect associations. The finding of an association between chronic psychiatric conditions and delayed return to usual health requires further evaluation. These findings have important implications for understanding the full effects of COVID-19, even in persons with milder outpatient illness.

Notably, convalescence can be prolonged even in young adults without chronic medical conditions, potentially leading to prolonged absence from work, studies, or other activities.

The authors of the study did note that this survey did have limitations.

1. This one is probably obvious, but, people who didn’t respond might have differed from the people who did respond – those with more severe illness might have been less likely to respond to telephone calls if they were subsequently hospitalized and unable to answer the telephone or those who recovered completely may have returned to life as normal

2. Some symptoms may have already been resolved before the test date or that commenced after the date of testing, and were thus not recorded in this survey

3. As a telephone survey, this study relied on patient self-report and might have been subject to incomplete recall or recall bias

All of those are a big deal, particularly with a sample size of just 270. That said, it does open the door for future study and give those studies a good starting to point to discover more data.

Survey of deaths and underlying conditions

Another survey, albeit rather morbid, compared people who have died from COVID-19 to the number of underlying conditions and what kind of underlying conditions those people were suffering from prior to death. The survey, titled, “Characteristics of Persons Who Died with COVID-19 — United States, February 12–May 18, 2020” tried to shed some light on which underlying conditions were most likely to be prevalent among those who died from COVID-19.

Like I said, a bit morbid. Necessary for the medical field to make progress, I know, but morbid.

The authors used a very large sample size in this case. More than 10,000 people (decedents) were included. Demographically, the authors report that in this study more than one third of Hispanic decedents (34.9%) and nearly one third (29.5%) of nonwhite decedents were younger than 65 years old, but only 13.2% of white decedents were younger than 65 years.

Previous studies have shown that approximately 75-percent of people who die from COVID-19 have one or more underlying medical conditions reported or were older than 65.

Among reported underlying medical conditions in this study, cardiovascular disease and diabetes were the most common.

The authors wrote:

Diabetes prevalence among decedents aged <65 years (49.6%) was substantially higher than that reported in an analysis of hospitalized COVID-19 patients aged <65 years (35%) and persons aged <65 years in the general population (<20%).

Among decedents aged <65 years, 7.8% died in an emergency department or at home; these out-of-hospital deaths might reflect lack of health care access, delays in seeking care, or diagnostic delays. Health communications campaigns could encourage patients, particularly those with underlying medical conditions, to seek medical care earlier in their illnesses.

Additionally, health care providers should be encouraged to consider the possibility of severe disease among younger persons who are Hispanic, nonwhite, or have underlying medical conditions. More prompt diagnoses could facilitate earlier implementation of supportive care to minimize morbidity among individuals and earlier isolation of contagious persons to protect communities from SARS-CoV-2 transmission.

Common underlying conditions:

| Condition | Total (Percent) |

| Cardio vascular Disease | 6,481 (60.9) |

| Diabetes | 4,210 (39.5) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 2,209 (20.8) |

| Chronic lung disease | 2,047 (19.2) |

| Immunosuppression | 1,661 (15.6) |

| Neurologic conditions | 1,376 (12.9) |

| Obesity | 918 (8.6) |

| End-stage renal disease | 368 (3.5) |

| Chronic liver conditions | 247 (2.3) |

Interesting to note, that the earliest studies suggested that Lung Disease was a common condition tied to COVID-19 deaths. In this study, it showed that people who died from COVID-19 with Lung Disease out-numbered those without it by at least 2-to-1, and for some age groups by almost 4-to-1. Yet, the authors noted that Lung Disease was still not one of the Top 2 underlying conditions found in those who died from COVID-19.

In fact, of the conditions listed, Chronic Kidney Disease out-numbers Lung Disease in those who died from COVID-19.

But there was a bit of an “unknown” problem to get over with respect to many of the underlying conditions. As for some people there wasn’t a clear indication that a person had or did not have a condition.

Tip to stay safe

This is information pulled straight from the CDC with no filter.

Wash your hands often

– Wash your hands often with soap and water for at least 20 seconds especially after you have been in a public place, or after blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing.

– It’s especially important to wash:

— Before eating or preparing food

— Before touching your face

— After using the restroom

— After leaving a public place

— After blowing your nose, coughing, or sneezing

— After handling your mask

— After changing a diaper

— After caring for someone sick

— After touching animals or pets

– If soap and water are not readily available, use a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol. Cover all surfaces of your hands and rub them together until they feel dry.

— Avoid touching your eyes, nose, and mouth with unwashed hands.

Avoid close contact

– Inside your home: Avoid close contact with people who are sick. If possible, maintain 6 feet between the person who is sick and other household members.

– Outside your home: Put 6 feet of distance between yourself and people who don’t live in your household.

Remember that some people without symptoms may be able to spread virus.

– Stay at least 6 feet (about 2 arms’ length) from other people.

– Keeping distance from others is especially important for people who are at higher risk of getting very sick.

Cover your mouth and nose with a mask when around others

– You could spread COVID-19 to others even if you do not feel sick.

– The mask is meant to protect other people in case you are infected.

– Everyone should wear a mask in public settings and when around people who don’t live in your household, especially when other social distancing measures are difficult to maintain.

– Masks should not be placed on young children under age 2, anyone who has trouble breathing, or is unconscious, incapacitated or otherwise unable to remove the mask without assistance.

– Do NOT use a mask meant for a healthcare worker. Currently, surgical masks and N95 respirators are critical supplies that should be reserved for healthcare workers and other first responders.

– Continue to keep about 6 feet between yourself and others. The mask is not a substitute for social distancing.

Cover coughs and sneezes</strong?

– Always cover your mouth and nose with a tissue when you cough or sneeze or use the inside of your elbow and do not spit.

– Throw used tissues in the trash.

– Immediately wash your hands with soap and water for at least 20 seconds. If soap and water are not readily available, clean your hands with a hand sanitizer that contains at least 60% alcohol.

Clean and disinfect

– Clean AND disinfect frequently touched surfaces daily. This includes tables, doorknobs, light switches, countertops, handles, desks, phones, keyboards, toilets, faucets, and sinks.

– If surfaces are dirty, clean them. Use detergent or soap and water prior to disinfection.

– Then, use a household disinfectant. Most common EPA-registered household disinfectantsexternal icon will work.

Monitor Your Health Daily

– Be alert for symptoms. Watch for fever, cough, shortness of breath, or other symptoms of COVID-19.

– Especially important if you are running essential errands, going into the office or workplace, and in settings where it may be difficult to keep a physical distance of 6 feet.

– Take your temperature if symptoms develop.

– Don’t take your temperature within 30 minutes of exercising or after taking medications that could lower your temperature, like acetaminophen.

– Follow CDC guidance if symptoms develop.

Stick to Weather Egg Head!!!! People of sick and tired of your ugly ass.