Well, when it comes to Invest 98K, I can tell you what I know. I can tell you what I don’t know. I can tell you what I can’t know (yet).

It is…

“Not a ton, yet.”

“A fair bit.”

“Some”

WHAT WE KNOW

This won’t be here tomorrow. The day after. Nor this weekend. Enjoy whatever you have planned.

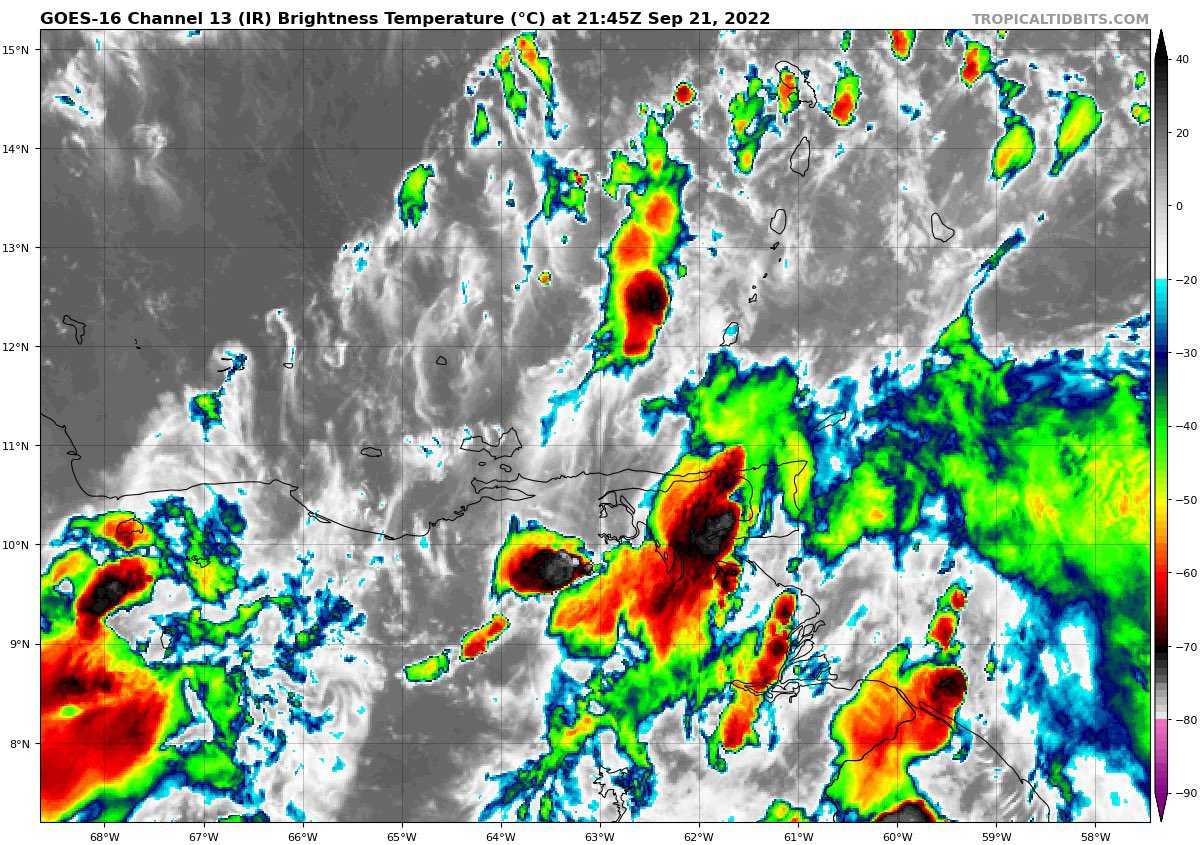

Here is a look at the vaunted Invest 98L tonight:

It isn’t pretty. It isn’t organized. And it doesn’t look anything like Fiona at this point. In fact, you may even notice the islands and land underneath a lot of the cloud cover. That is South America! Yes. South America.

This thing is pretty far south for a tropical wave and that is influencing a lot of what is happening with the system currently and with the how the modeling is handling its future. Systems this far south are rarely factors

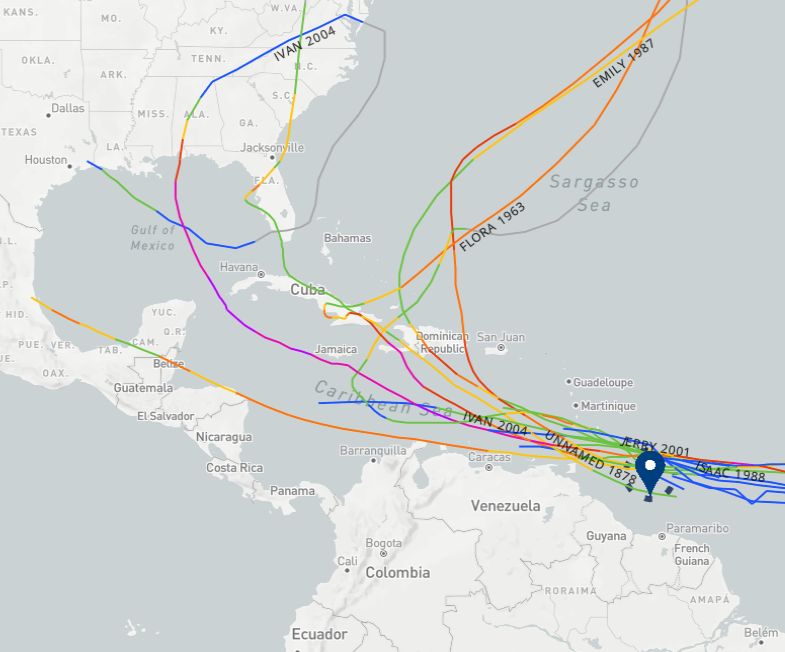

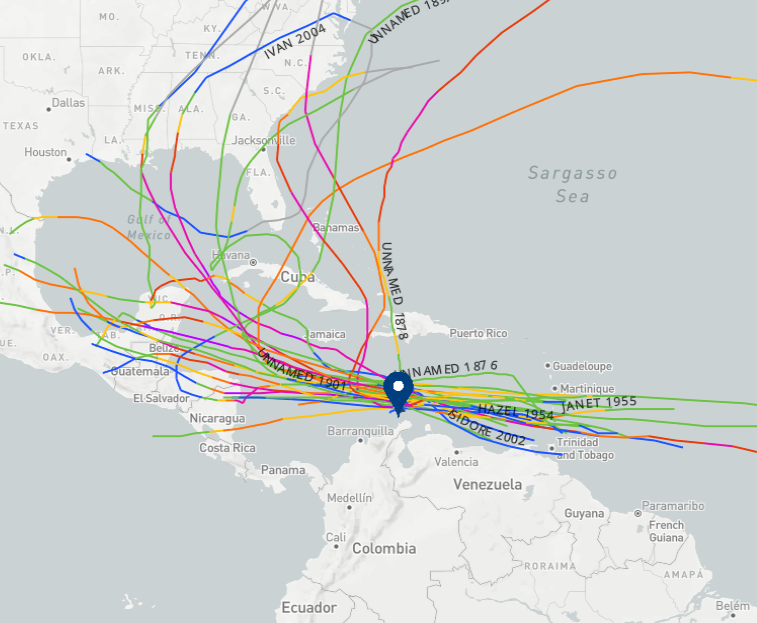

In fact, if you compare how many landfalling tropical systems formed in the region it is in right now versus where it is expected to be when it forms… the latter is much higher. We go from two storms to 10 named storms making landfall. Six are along the Gulf Coast. One of those, Ivan, made landfall twice!

That said, that is since the 1800s. So it isn’t like there is a high recurrence rate of landfalling tropical systems from this region of the Atlantic this late in the season.

We also know that the water is very warm.

Even without a legend or a key, I think you can all figure out where the warmest water is. And that is going to be where this system has a chance to travel.

WHAT WE DON’T KNOW

This list is a bit longer and a bit more nuanced. This is stuff we don’t know specifically, even if we can make an estimation or a forecast about it.

First I wanted to point out a “fun fact” that two of the recent typhoons in the Pacific are playing a role in the potential outcome of Invest 98L. Not too often that this happens, but kind of a neat thing to remind us that all weather somewhere is connected to weather somewhere else.

But we don’t know how all of that is going to shake out. That operational model shown above is just one potential outcome in a sea (no pun intended) of potential outcomes depending on which model we choose.

Which one is “right” and which are not? There isn’t one that is 100-percent correct. Instead, we use these as guidance.

Note the tracks below from the operational hurricane guidance suggesting a pop north in the coming 48 hours that flattens west and then rises north into the Gulf.

This is due to interaction with the “exhaust” from Fiona (seriously!) across the eastern Caribbean and then the eventual break in the ridging allowing it to drift northward. The interesting thing about this particular system is that a “stronger” system isn’t going to be more likely to move north faster than a weaker system.

We get a hint from that from looking at some of the other model guidance. Notice the similar trend from all of these spaghettis. But look closely at the “TABD” line. That one goes across South America and then jets north. The “sister” models are the “TABS” and the “TABM” which end up looking similar.

These models are a “Deep” “Shallow” and “Medium” estimate for storm track based on convection around the system. And “Deep” convection is an indication of a well-establish storm while a “Shallow” system is disorganized and messy. The “Medium” is inbetween.

This is why we look at these as “guidance” and not as “truth” because what we can learn here is that the TABD model suggests a stronger storm stays south until – at some point – what every is making it stay south changes and then it can do what all strong storms want to do: go toward the north pole.

But what’s the haps?! Upper level winds are “the haps.”

Looking at the 200mb wind map (looking about 25,000ft and higher) for tomorrow, it shows the exhaust from Fiona is shoving 98L toward the south. And if the system was stronger and had deeper convection it would be much more influenced by this wind. And that influence would push it south.

And notice how it drops off almost completely by the time you get toward the central Caribbean. That is when the TABD jetted things northward.

But if a system isn’t as organized and doesn’t have as deep of convection, it will just slide WNW. We can then use that information to make better decisions about what we see in two places… Firstly, when we look at the ensemble guidance and can start to make assessments as to what the model guidance is “seeing” and “not seeing” and secondly, if you see any meteorologist saying, “The stronger it gets the faster it will go north” you can know that person hasn’t done all of their research 😜 .

Looking at the spaghettis from the EPS and GEFS, notice it is showing a similar trend. The stronger storms earlier fade more south than others and storms that are stronger later jet more northward. So we are seeing that exhausting at play. And that when it is no longer in play, it acts like a normal tropical system.

The EPS seems to show two camps. One camp in the eastern Gulf the other into the Yucatan. The GEFS is a bit more evenly spread, but most of it is into the central and eastern Gulf.

Based on this, while I don’t “know” I would forecast that the western Gulf – from about Morgan City, Louisiana to the west until Corpus Christi, Texas is probably “okay” for the moment. Things may change, but the data supports you guys being able to at least breathe a bit easier for now. If I’m south of Corpus, I might still be watching this pretty closely. And if I’m east of Morgan City, Louisiana, I’m watching this VERY closely.

And those potential tracks line up with history too. Historically, the weaknesses for tropical system, at that point in the Caribbean, is to move due west into Mexico or north and northeast into the Gulf.

How strong of a tropical system are we looking at? Again this isn’t something we “know” but the model guidance suggests that in 72 hours we are still going to be looking at a Tropical Storm. And beyond that point is when things are suggested to take off.

But one gigantic asterisk here is that model guidance for tropical system intensity is often very poor beyond 72 hours.

Looking out pretty far I want to show something, not to scare anyone but to give you an idea about the potential size and scope of this system. Plus, I can guarantee people are going to find this image elsewhere and take it as fact. And I want to let everyone know, this is not a fact. This isn’t likely. This is “possible,” sure. But I wouldn’t bet even a penny on it verifying.

My point with showing this is to show just how fat this storm may be if things shake out in a way that allow it to tape into the warm waters, it can go through one or two Eyewall Replacement Cycles and it can have a solid upper-level ridge overhead. In terms of physical size, it could get pretty hefty. But remember that just because something is fatter doesn’t mean it is stronger or more damaging.

WHAT WE CAN’T KNOW

Where this thing will be, specifically, in a few days, in a week, at landfall. We just can’t do it. I know a lot of folks reading this want to know, “Do I need to worry?” and I would say that “no” you don’t need to “worry” at this point. Just keep up with the forecast.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Whatever is out there won’t be somewhere near the US for, at least, another seven days. Probably more like 10 days before it is knocking on anyone’s door.

If you live anywhere from about New Orleans to Miami you should probably double-check your Hurricane Prep Kit. You may not need it, but I’d check it to make sure it is ready to go. If you live along the water, I’d double check the evacuation routes. If you live inland I’d double check around the house to make sure there aren’t any loose branches on trees or leaves clogging up the gutters and storm drains in the roads.

The nice thing about being prepared is it gives you peace of mind. And it makes the storm not as bad if/when it rolls through. The old saying, “An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of recover” is so true.

One thought on “9/21/22 645p Tropical Update: Invest 98L and what it means – or doesn’t mean – for the Gulf”

Comments are closed.