Good morning, folks! Overnight, the National Hurricane Center added another region that they’re watching for the potential for tropical cyclone development, this time much closer to home in the northern Gulf of Mexico – As Sincere said in the last post, even though it’s still early in the season, we’re keeping a close eye on these two disturbances and any hazards that they may bring.

Checking in with the NHC

As of the 1:00 AM update, the National Hurricane Center is now watching two areas in the Atlantic Basin, the first of which is associated with the tropical wave we’ve been watching all week currently located south of 15N along 33W, or about 700 miles southwest of Cape Verde; the second is a newly-added region in the northern Gulf of Mexico where a weak low pressure may form early next week.

Per the NHC, the system in the northern Gulf of Mexico has a 0% chance to develop within the next 48 hours and a 20% chance to develop within the next 5 days; the disturbance 700 southwest of Cape Verde has a 20% chance to develop within the next 48 hours, and a 60% chance within the next 5 days.

Current Conditions in the Tropics

Taking a look at mid-level water vapor imagery, we’re watching three disturbances located along the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) between West Africa and the northern coast of South America, a fourth disturbance currently located over the Southeast, and Tropical Storm Celia, which is labeled as disturbance 5 above. The two regions that the NHC is watching for possible development are due to Disturbance 2 and Disturbance 4.

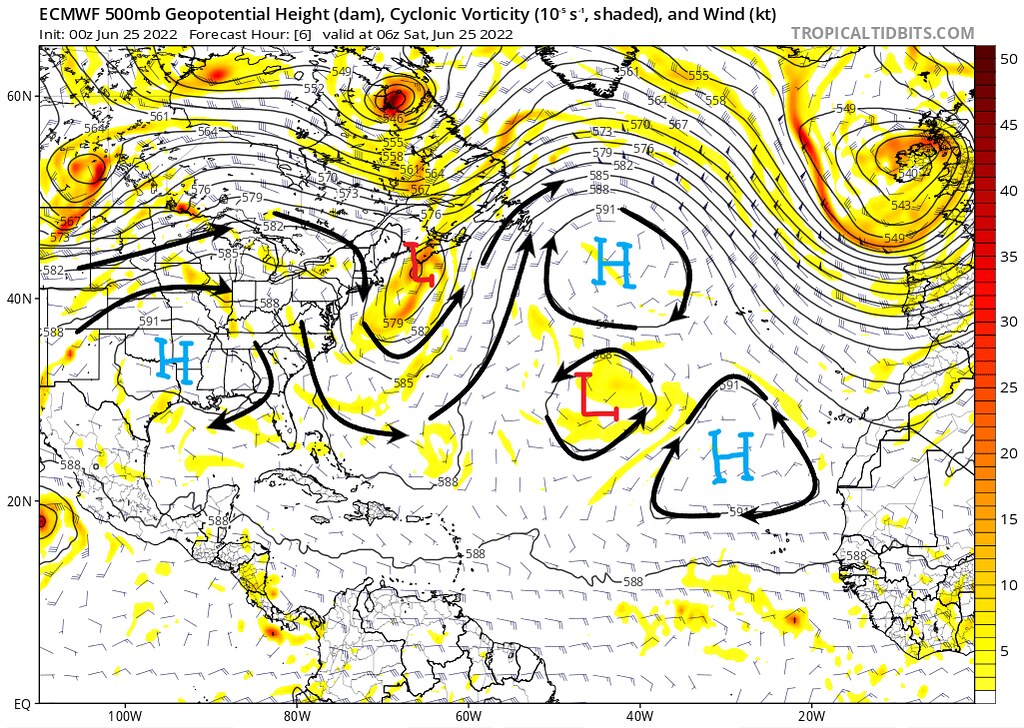

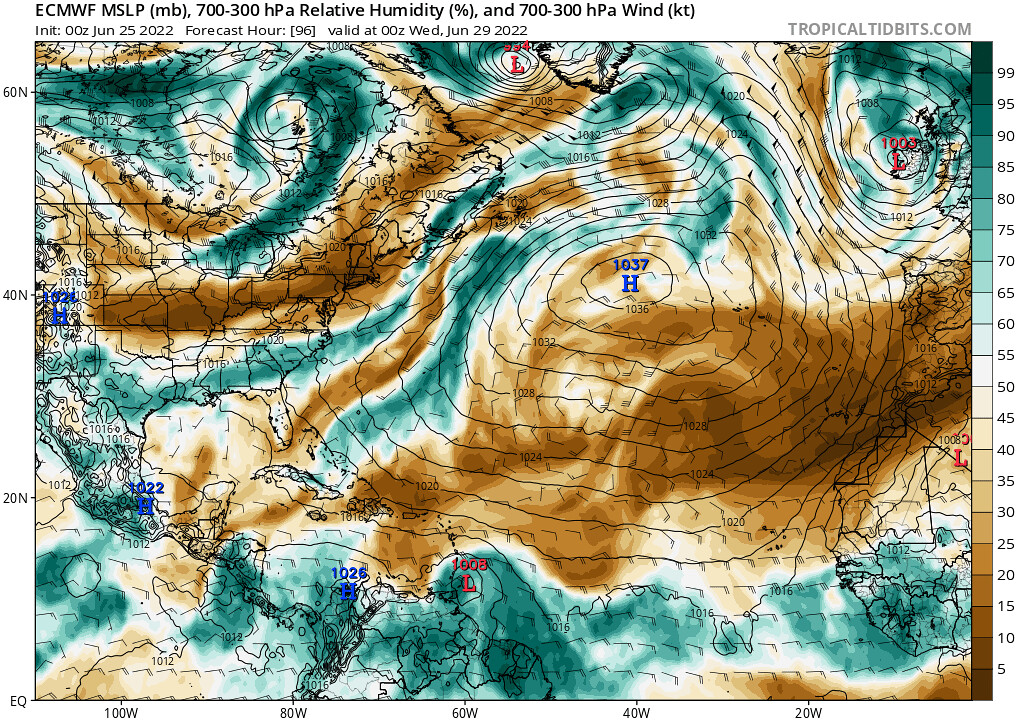

The 00z ECMWF run from this morning shows us the upper-level steering patters currently present in the Atlantic Basin. In the middle of the Atlantic sits the subtropical high, which is broken up some by a weak upper-level low pressure. A deep ridge is in place off of the East Coast, and to the west, a ridge is located over the Southern US.

To the south of the right-most high pressure are Disturbances 1-3, which will continue to move westward throughout the coming days. Disturbance is located underneath an area of upper-level divergence over Florida, which has been responsible for the development of a weak surface low pressure and associated showers and thunderstorms in region.

As far as wind shear, I’m not gonna lie, it’s looking pretty rough out there. The only real lulls exist along the ITCZ where Disturbances 1-3 are, and there is some relatively light wind shear as well around where Disturbance 4 is located, as well as for most of the Gulf of Mexico. In the middle of the Atlantic, most of the shear is the result of the easterly surface winds underneath the mid-level westerlies of the subtropical jet. Over the continental US, however, a tremendous amount of shear is due to the upper-level trough exiting the East Coast, and its interaction with the ridge over the South.

The relative humidity paints a similar, hostile picture, with large bodies of dry air across most of the Atlantic, and only a sliver of moist air along the ITCZ. In the Gulf, the only sustainable relative humidity values are a result of the convection associated with Disturbance 4.

As far as the disturbances along the ITCZ, Disturbance 3, the leader of the group, is dealing with a very sharp moisture gradient and will likely not be able to sustain convection. While this is bad news for Disturbance 3, it is setting the stage for a more favorable environment for the disturbances behind it as it moistens the atmosphere.

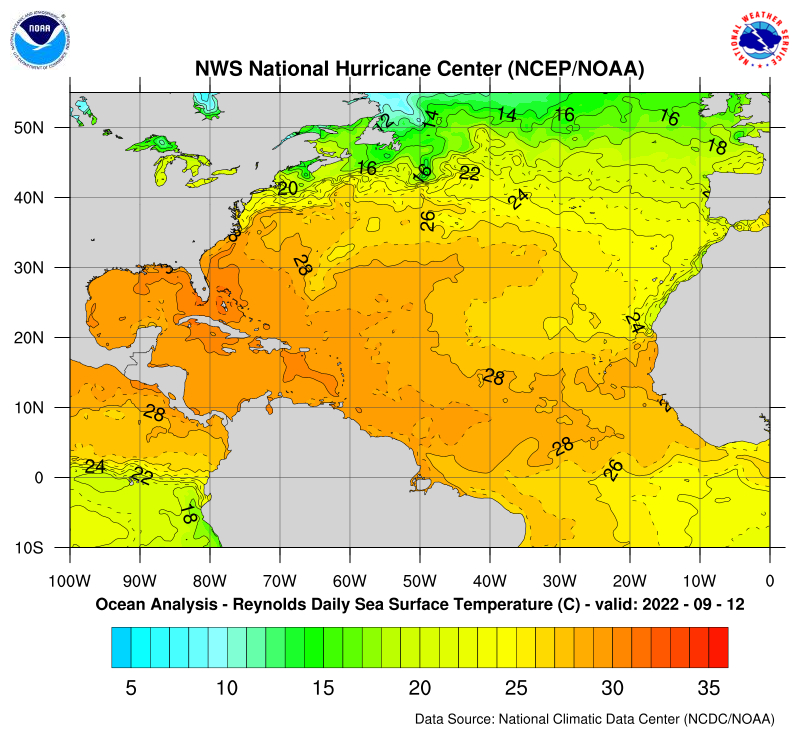

Lastly, it is important to look at the sea surface temperatures (SSTs) as they are the driving force for the energy of a tropical cyclone. As I mentioned in my last post, temperatures above 26 C are required for tropical cyclones to develop. In the main development region (MDR), the Caribbean and the Gulf of Mexico, the SSTs are more than warm enough to support tropical cyclogenesis. In fact, the warmest waters in this graphic are located in the northern Gulf of Mexico, in the region highlighted by the National Hurricane Center for the potential development of Disturbance 4.

Disturbance in the Gulf of Mexico

First, let’s look in depth at the disturbance in the Gulf of Mexico, as it’s the closest to home. As we’ve already examined, the SSTs are warm enough to support the development of a tropical cyclone, but the shear in the Gulf of Mexico is relatively strong, and there is very little moisture as well.

By 1 PM Tuesday, the wind shear over the region will have improved somewhat, according to both the GFS and the ECMWF, with the shear looking slightly more favorable in the GFS run. The shear situation is largely similar to the situation now, as the first upper-level ridge over the region retreats westward and weakens, and the interaction between the upper-level low off the East Coast and a strengthening ridge off the Southeast Coast lead to relatively high wind shear values off the coast of Florida.

The relative humidity does not change much either, however there is a general increase in the moisture in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Once again, both models are similar, however the GFS shows a more favorable situation where there is more moisture in the atmosphere for a developing tropical cyclone to work with. It is worth noting, however, that there is still a significant amount of dry air present in the atmosphere, so if a system does develop a closed circulation, it will likely suffer setbacks as it draws in dry air from the southern Gulf and off the Southeast Coast.

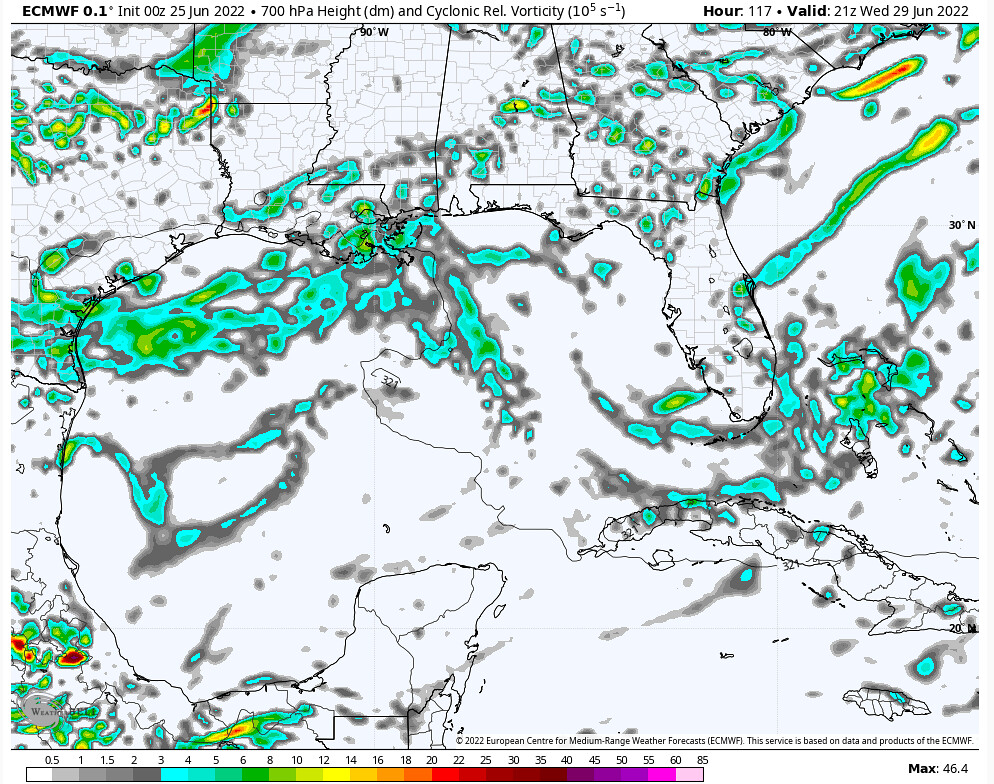

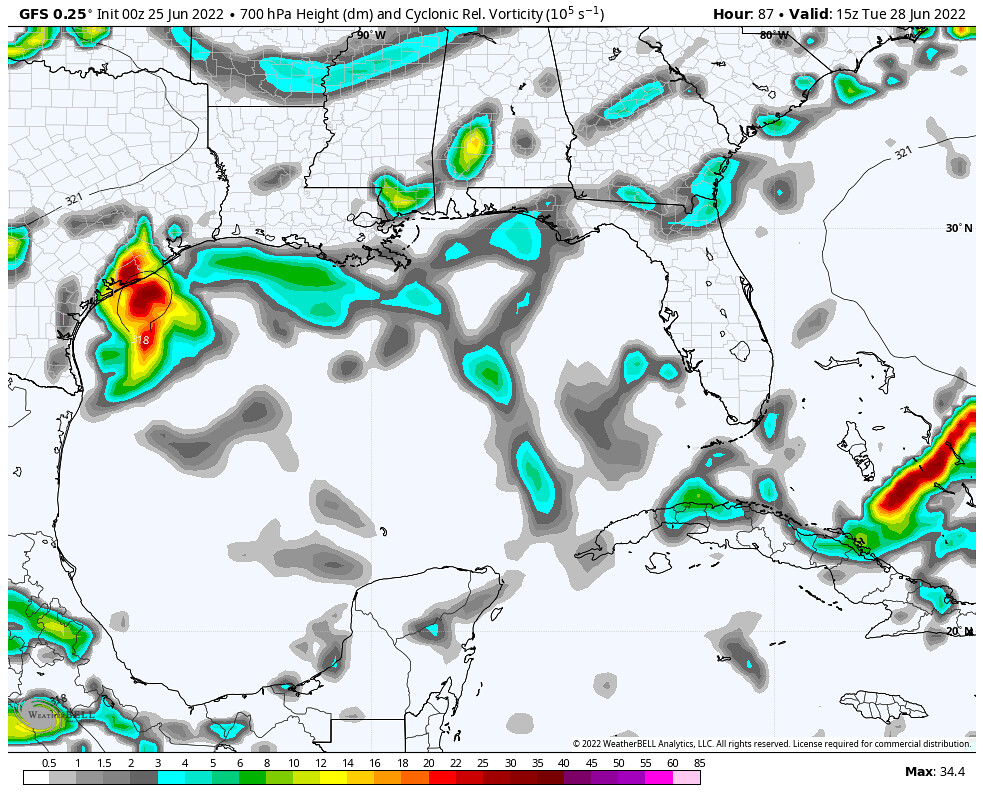

When all is said and done, however, the 00z June 25 run of the ECMWF fails to form a consolidated velocity signature indicative of a developing tropical cyclone before the disturbance moves onshore in southern Texas on Wednesday afternoon. The GFS on the other hand, does show a weak velocity signature at 700mb, showing that the system is attempting to form a tighter circulation before coming ashore around the same time Wednesday afternoon. At this time, the main constraints inhibiting this disturbance from undergoing tropical cyclogenesis are the lack of moisture and the limited time it has over the warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico.

Invest 94L

As I had mentioned earlier, the National Hurricane Center has assigned the tropical wave 700 miles southwest of the Cape Verde Islands as Invest 94L, however throughout this discussion, we’ve been referring to this system as Disturbance 2.

We’ve already analyzed the steering mechanisms behind this disturbance, so let’s jump right in by looking at how the wind shear develops over time.

As of Sunday evening, both the ECMWF and the GFS have similar solutions, with the GFS once again being the more favorable of the two models as shear is lesser on a bigger scale, however it is also important to note that the the developing circulation as show in the ECMWF is in a localized region of very little shear.

By Tuesday evening, the low pressure center of the disturbance can be identified easily on both the ECMWF and GFS. Generally speaking, the wind shear around the disturbance is lesser in the GFS model output than the ECMWF output – however, it is also worth noting that the ECMWF have a stronger system at this time.

Changing gears to view the mid- and upper-level relative humidity differences among the GFS and ECMWF: while they are once again largely similar, the ECMWF does have more moisture near the system, and more importantly has the disturbance surrounded by humid air. One difference between the two models is the that, while the European solution has a better-developed cyclone, there is much more dry air in the Gulf of Mexico, and associated with the other tropical waves exiting Africa than in the GFS solution.

By Friday evening, both the ECMWF and the GFS model solutions show developing tropical cyclones in similar locations at similar strengths. The ECMWF is once again the drier solution, however the tropical cyclone is not being exposed to dry air. By this time, the European model also shows a slightly stronger system, this is likely because of the fact that the disturbance was able to enter an environment where dry air was removed from the developing cyclone faster than the GFS model.

Finally, by Friday evening, both models depict a strengthening tropical cyclone approaching Nicaragua. It’s honestly quite remarkable that at 6 days out, both the ECMWF and the GFS have a tropical cyclone in pretty much the same location, with similar intensities. That being said, just because the models agree right now does not mean that they will for future runs, as model errors are significant at 6 days out.

Above are the ECMWF and GFS ensemble member forecast tracks for this disturbance. There is good agreement that this system will take some time to get organized as it moves west toward the southern Windward Islands. Both ensemble outputs suggest that a weaker system would likely remain further south, and that a stronger system would likely curve northward toward Honduras, Belize and Mexico.

While there are still uncertainties regarding the strength of this tropical cyclone and where it will end up, there is a general consensus that a developing tropical cyclone will affect the southern Windward Islands beginning Tuesday evening, with impacts possible for locations in the southern Caribbean through the end of the week.