Good morning and Happy Humpday!

Even though the Atlantic Hurricane season has been underwhelming so far, with the Basin not churning out a single tropical cyclone since Tropical Storm Colin on July 2 (a storm that dissipated only a day later) – that doesn’t mean that the it’s time to sleep on the Atlantic. We are approaching the peak of hurricane season after all…

And on that note, let’s take a look at the systems that the National Hurricane Center is watching for potential development, as well as the environment across the tropics to see for ourselves what will become of these disturbances down the road.

Two Areas of Interest from the National Hurricane Center

Just as the title for this section suggests, the National Hurricane Center is watching two disturbances in the Tropical Atlantic that have a shot at becoming tropical cyclones over the next five days. The first system is currently just north of the French Guiana and Suriname and is given a 20% chance of formation in the next five days. The second disturbance is currently still over West Africa, and as it moves over the Eastern Atlantic, the NHC has also given it a 20% chance of formation in the next 5 days.

These disturbances are a bit easier to make out with water-vapor imagery, with the disturbances circled and numbered for convenience.

Current Tropical Environment

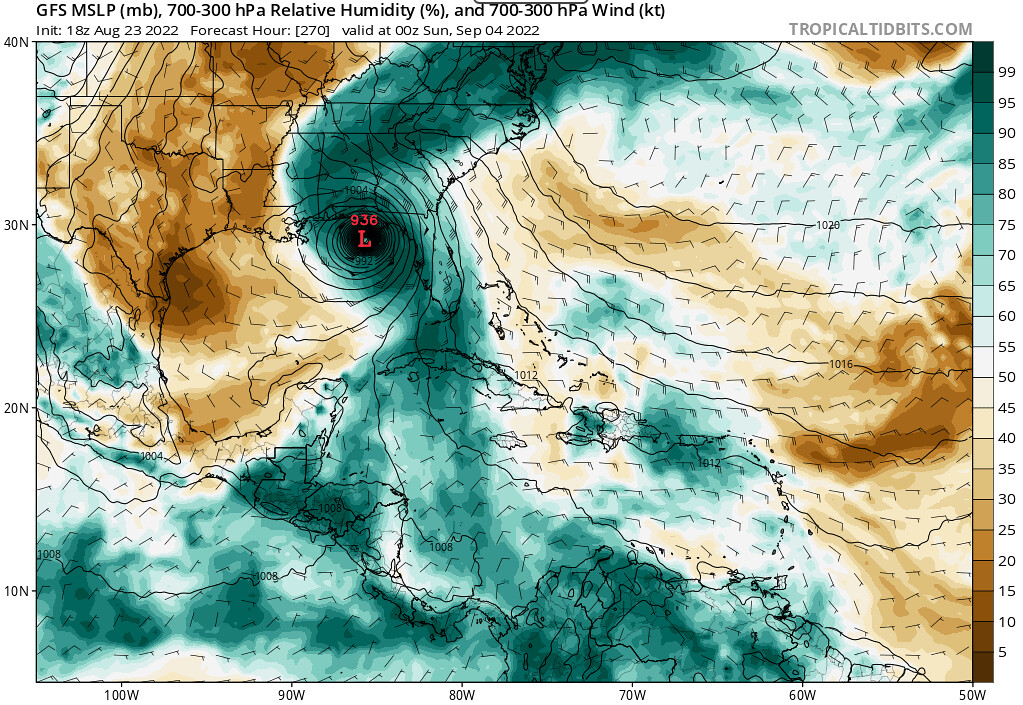

Apart from the two disturbances visible in the mid-level water vapor imagery shown above, other features are noticeable, too. The first of which is the ever-present plume of dry air across to the north of the intertropical convergence zone (ICTZ). This can be seen better in a plot of mid-to-upper-level average relative humidities, which shows a very dry airmass over much of the central North Atlantic.

In fact, the only appreciable belt region of moisture in the Eastern Tropical Atlantic is along the ITCZ from West Africa toward the northern portion of South America. Elsewhere, sufficient moisture exists in the Caribbean Sea and the northern Gulf of Mexico.

The only regions with low wind shear across the Tropical Atlantic exist on the northern fringes of the ITCZ in the eastern North Atlantic and into portions of the Caribbean Sea. There are two regions of upper-level lows that are responsible for some higher wind shear values for much of the Gulf of Mexico and portions of the western North Atlantic north of Puerto Rico.

As far as our systems go, Disturbance 1 (which is not marked by a low pressure center in either image in this section) is in a relatively favorable region with respect to wind shear, however is currently experiencing some dry air to the north, which is hampering convection at the moment. Disturbance 2 still has a long way to go until it reaches the Atlantic, but when it does late this week, the shear will begin to ease up, allowing the disturbance some time for convection to organize.

With that being said, as Disturbance 1 entering a more favorable environment sooner and its position closer to the US, let’s take some extra time to focus on this system…

Model Outlook

As we have already established, Disturbance 1 is the biggest threat to the United States at the moment, as it is closer to the country and will enter a more favorable environment sooner… and that’s about the only thing that the GFS and ECMWF models seem to be agreeing with at the moment, as they have very different outcomes for this system.

Let’s start with the ECMWF solution, shall we?

The European ECMWF model already has this disturbance struggling with some dry air to the north and west of the system by this evening – a solution that is actually shown by the GFS as well. However this run of the ECMWF shows that this system fails to overcome this dry air, showing a much weaker disturbance by the weekend.

And, by the end of the 12z run of the ECMWF, the disturbance still has not yet developed into anything more than a weak area of showers and thunderstorms…

Now, to the GFS

The GFS on the other hand has the disturbance overcoming the drier air and eventually organizing into a consolidated tropical cyclone by the beginning of next week.

Later, in typical GFS-fashion, despite the cyclone moving over the hilly terrain of Cuba, the storm rapidly intensifies into a major hurricane, making landfall along somewhere along the Gulf Coast just in time for Labor Day Weekend.

While neither of these solutions will likely be the actual outcome of this disturbance, the vastly different model solutions for this system represent the high level of uncertainty for a disturbance 10 days out. It is important to not take one output from one model solution and run with it, especially when the potential impacts are still more than a week away.

With that being said, the peak of hurricane season is in mid-September, so folks up and down the east coast should be weary of potential tropical cyclone impacts this time of year; and, as we’ve seen, it is not out of the question that this particular disturbance gets it act together and threatens the US at some point. The best we can do at this time is to keep our eyes on this disturbance and wait for more models to come into agreement with the evolution of this storm.

Conclusions

While the Atlantic Hurricane Season has been very inactive thus far, conditions in the Atlantic Basin are favorable enough to potentially support the development of tropical cyclones in the next few weeks, especially as the peak of hurricane season approaches. With the National Hurricane Center now watching two disturbances in the Tropics, it seems that our days of a quiet Atlantic are coming to an end as the Atlantic Hurricane Season begins to ramp up.