It only takes one. That could be all that is in this post. Because it is true. It only takes one hurricane to make it a “active” season.

If there is only one hurricane the rest of the year. And that hurricane is a Category Five. And that Category Five hits your house. That is a bad year for you. That is an active year for you. Even if there are only four named storms, three hurricanes and one major hurricane. That is technically a “below average” year. But if that below average year takes your home, and you are unprepared, then it is a really bad year for you.

So what does a “below average” year really mean? We’ll get there. But first lets set some ground rules.

The official forecast

As we learned from a retired professor from the University of Southern Mississippi earlier this year, these seasonal forecasts may not be that great. But, despite that, here is the latest forecast from the Climate Prediction Center:

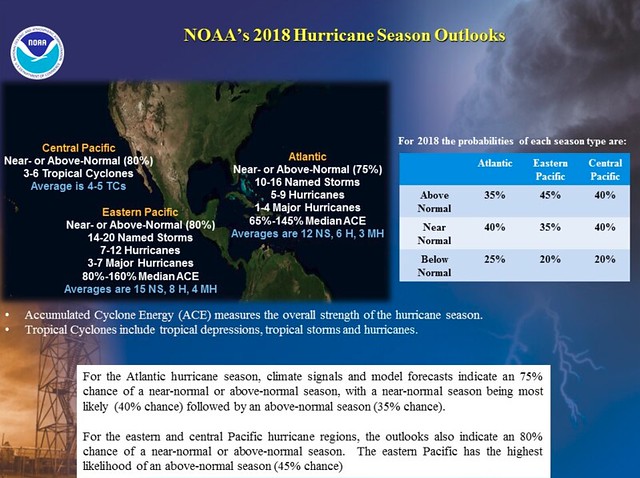

NOAA’s outlook for the 2018 Atlantic Hurricane Season indicates that a near-normal season is most likely (40% chance), followed by a 35% chance of an above-normal season and a 25% chance of a below-normal season. See NOAA definitions of above-, near-, and below-normal seasons.

An important measure of the total seasonal activity is NOAA’s Accumulated Cyclone Energy (ACE) index, which accounts for the combined intensity and duration of named storms and hurricanes during the season. This 2018 outlook indicates a 70% chance that the seasonal ACE range will be 65%-145% of the median. According to NOAA’s hurricane season classifications, an ACE value between 71.4% and 120% of the 1981-2010 median reflects a near-normal season. Values above this range reflect an above-normal season, and values below this range reflect a below-normal season.

The 2018 Atlantic hurricane season is predicted to produce (with 70% probability for each range) 10-16 named storms, of which 5-9 are expected to become hurricanes, and 1-4 of those are expected to become major hurricanes. These ranges are centered near or above the 1981-2010 period averages of about 12 named storms, 6 hurricanes and 3 major hurricanes.

Predicting the location, number, timing, and strength of hurricane landfalls are ultimately related to the daily weather patterns, storm genesis locations and steering patterns. These patterns are not predictable weeks or months in advance. As a result, it is currently not possible to reliably predict the number or intensity of landfalling hurricanes at these extended ranges, or whether a given locality will be impacted by a hurricane this season. Therefore, NOAA does not make an official seasonal hurricane landfall outlook.

Colorado State, WeatherBell, and a host of to hers – as well as Billy bob’s Super Weather Authority facebook page – seem to ahve their own forecast. Some good. Some not.

But the official forecast from May 24th from the CPC is blocked out above.

Some Stats: Reading between the lines

A couple of quick hit notes, it I may…

Despite it being reported as a forecast for a “below average season” there is only 1-in-4 shot that it is below average. One out of four! That is, like, a shade above the Mendoza line. It is far from a lock that we will be hurricane-free.

According to John Cangialosi and Robbie Berg at National Hurricane Center, 30 percent of tropical systems form via non-tropical waves (decaying fronts, thunderstorm clusters, etc). That is almost a 1-in-3 shot that a tropical system forms from something other than a tropical wave coming off of Africa.

The range of one-to-four Major Hurricanes can be likened to the range of one to four cheeseburgers for dinner. One is plenty. Four is a disaster for your digestive system.

So what is all this talk about below average?

One thing we have been talking about a lot during the past few weeks is the cooler than average sea-surface temperatures across the Atlantic. We aren’t alone. Others have, too.

Early July-averaged tropical Atlantic (10-20°N, 60-20°W) sea surface temperatures (SSTs) are the coldest since 1994 and about 0.5°C below the long-term average. Typically colder tropical Atlantic SSTs favor less Atlantic #hurricane activity, especially in the deep tropics. pic.twitter.com/VxJWHzXCyB

— Philip Klotzbach (@philklotzbach) July 11, 2018

As an aside, Philip Klotzbach is a Colorado State meteorologist who is quite versed in Atlantic Hurricane season information.

The thought is that if temperatures are cooler out to sea in the open Atlantic, then it is more difficult for hurricanes to form further out to sea in the open Atlantic. Thus lowering the overall number of storms that develop.

Sadly, it’s not that simple, though

For multiple reasons. One of which was pointed out by someone on twitter a few days ago:

👀

June 2018 200mb temperatures were cooler than June 2017's in most of the Atlantic basin. If this persists, it would allow convection to become stronger than avg w/ cooler SSTs. pic.twitter.com/hiK8zs5QOj

— Not Sparta (@NotSparta_wx) July 11, 2018

The idea that if the upper atmosphere is cooler, then the lower atmosphere doesn’t have to be as warm is a simple – albeit, probably effective – approach to explaining Beryl. Since A colder atmosphere aloft increases instability at the surface, it wouldn’t take as much heat at the surface to create storms.

Seems simple enough, right?

Maybe not. Because of Chaos Theory. Chaos Theory has been discussed here before. It holds true when producing seasonal forecasts, too.

So far this season, we have seen an early-season Subtropical storm (Alberto), a wave form into Hurricane Beryl well east of the Antilles Islands in early July form over those cooler-than-average waters, and Hurricane Chris form off the coast of the Carolinas from the end of a passing front.

Alberto was Subtropical, Beryl was really far to the south, Chris traversed a plume of warmer water.

Three different storms, three unique situations that led to named storms. Two affected populated areas.

So it isn’t as easy as saying a “below average” season means fewer should worry. Because for those directly affected by Alberto and Beryl, it has been an active season. They’ve had a storm already. And it is only mid-July!

So what, then, Nick? What should we do?

The same thing you do every year. Prepare like a hurricane could hit your house. Stock up on supplies. Check your insurance. Make sure your home is hurricane ready.