There have been a lot of wild rumors floating around the interwebs during the past few weeks regarding the possibility for some serious cold air dropping south out of Canada. Rumors of a foot of snow in Mississippi and Alabama, sub-zero wind chills in Florida, and an ice storm for the entire Texas Gulf Coast top the list of improbable scenarios.

Fighting against the Misinformation Monsters on social media may seem like an uphill battle with no victories, because it is. For every rumor squashed, two more rise from the ashes. Winter weather rumors are Bebe’s kids: They don’t die, they multiple.

While the Hype Train is always ready to stir the pot and get people clicking share, there are some responsible people on social media. Big props to Evan Brantley for keeping it truthful.

Yes it appears cold air is coming, but b4 you start posting explicit temp maps, keep in mind the 12Z GFS 850mb temps are greater than 10C colder than all time recorded coldest temps in many locations (DVN shown). The odds of breaking all-time records by 10C is nearly zero. 1/2 pic.twitter.com/jZCUsVg5AO

— Evan Bentley (@evan_bentley) January 24, 2019

So, what can you believe? What is the difference between possible and probable? Hows does all this weather forecasting stuff work anyway?

I thought you’d never ask!

Believable weather information

With life, believability is often commensurate with trustworthiness. Information from trusted people is often believed. But with weather, for whatever reason, information can be believed even if there is no developed trust. Casual observation leads me the believe that this is because people ‘hope’ that certain weather information is true or that it is false. They either want snow, or don’t want snow. So, because a certain piece of information reinforces their beliefs, they believe it.

That is why it is important to question the believability of information – all of it, not just weather – you stumble across on social media. People will write headlines and post information that is misleading because they know it will get your attention. Social media can be turned into a very seedy place very quickly.

Old clickbait was just “you won’t believe what happened when _____ ” but new clickbait is playing more to your subconscious. Because it works just as well, and you aren’t as aware.

Anymore, a decent rule of thumb may be: If a weather post doesn’t grab your attention with a map featuring outlandish forecast data and a catchy headline promising record-breaking conditions, it probably contains trustworthy information.

Though, that doesn’t save you from inaccurate information. So, maybe just scratch that.

Possible vs Probable

This one is pretty straight-forward. the probability is the measure of the likelihood of an event, the possibility is a measure of the chance that an event even exists.

For example, there is the possibility that it snows in the South next week. The possibility is, frankly, high.

But the probability that it snows is, at this point given the available data, low.

But why is that? Variability within the data is the key here. At this distance in time there are too many variables within the future forecast that are still unknowns. And they are unknowns with high variance. The graphic here illustrates how many possible outcomes there are when a decision matrix has three options and three steps.

Imagine if each choice at each step is reasonably accurate within the frame of reference established. Could you make an informed decision?

I would argue, probably not.

A good example of this conundrum may be the 850mb temperature (the temperature up at 4,000 feet) next Tuesday when precipitation will be falling in South Mississippi.

In this situation, the 850mb temperature is a big indicator of precipitation type. And right now, a big unknown.

850mb temperatures from Pivotal Weather via GIPHY

Further complicating things, the variance between the incoming available data is still pretty large. Every six hours, between the model data available, that temperature is fluctuating at a range of about 7 degrees. And, as you can see on the graphics above, it is flip-flopping between being above and below freezing.

If the temperature is above freezing, the precipitation type is rain, sleet or freezing rain. If it is below freezing, it can be (but isn’t always) snow.

But each new chunk of data is reasonably accurate within the frame of reference established. So it is difficult to make an informed decision. And thus to offer an accurate forecast.

The argument is then, ‘well pick one. that’s your job.’

But I already have. The forecast for South Mississippi is currently a cold rain. In this case, I’m using history (snow doesn’t often fall) and recent experience (model guidance has suggested multiple cold shots and chances for snow since Christmas that have all failed to materialize) to come to a forecast.

But the forecast will likely change as more data is available and as the variability between that data decreases.

How does weather forecasting even work?

Basically as described above. Mathematical possibility versus probability is put into a decision matrix and evidence for the most likely scenario given the available data is followed to an outcome. That outcome is the forecast.

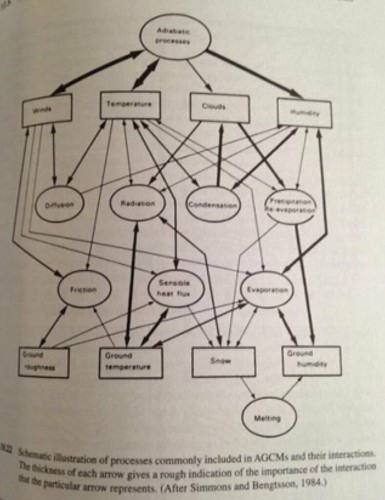

The main difference is the decision matrix used isn’t linear, and it looks more like this…

That was actually pulled out of a textbook I use to teach my Severe Weather Forecasting class. And I think it highlights a good point.

Boiled down, that means that when variability within the data is high, the possibility of an event is also high. But the probability of that event is low.

Applying that to weather forecasts and model data: That is why there is always a snowstorm coming to the Gulf Coast “next week,” or further into the future, shown in model data. The variability for a bunch of specific parameters within the available weather model data is high. That means the models output could include multiple possibilities (like snow!) even though the probability is low.

Experienced meteorologists and forecasters recognize this. And protect errors from sneaking into their forecast by keeping this in mind when forecasting. New ones may not.

The general public has no reason to know this at all – until now! Knowing this can really help, though, guard you from some of the things discussed above like crazy weather posts on social media and understanding when meteorologists say things are possible but not probable.

That’s great, Nick, but I’m just here for the forecast…

Southern Louisiana, southern Mississippi and lower Alabama:

Right now, the forecast calls for colder air to dump south toward the Gulf Coast on Tuesday of next week. Ahead of the cold air will be a band of light to moderate rain. As the leading edge of the cold air digs under the rain, a change-over to sleet/snow will be possible before precipitation comes to an end.

Rainfall is likely going to begin Tuesday morning. The change-over may occur between 1p and 6p on Tuesday afternoon – depending on your location. Further north, the change-over may happen earlier in the day. If you live further south, the change-over may wait until later.

But, confidence in a change-over occuring is increasing.

Precipitation-type totals (how much snow versus rain versus sleet) are a big unknown at this point as the variance between the available data is too high to offer a forecast with any accuracy. Again, because variance is high, possibilities are high, but probabilities are low. This is why model data, and maps you may see on social media, may show wild and outlandish precipitation potential.

Keep in mind with each successive batch of model data, the picture becomes clearer but accurate forecasts on some specifics (like precipitation-type total estimates) are simply not possible until you are within 72 hours out.