A La Nina Watch was issued by NOAA today. That means there is a 55- to 60-percent chance that a La Nina forms this fall or winter.

What is La Nina

La Nina is an when the Pacific Ocean waters off the coast of South America run cooler than average. In fact, it is when they are greater than 0.5 degree below average. The atmosphere – globally! – responds to this change. The cooler water temperatures moves the jet stream to different areas and increases the chances that different weather to happen in different areas.

The textbook definition of La Nina from NOAA sounds like this:

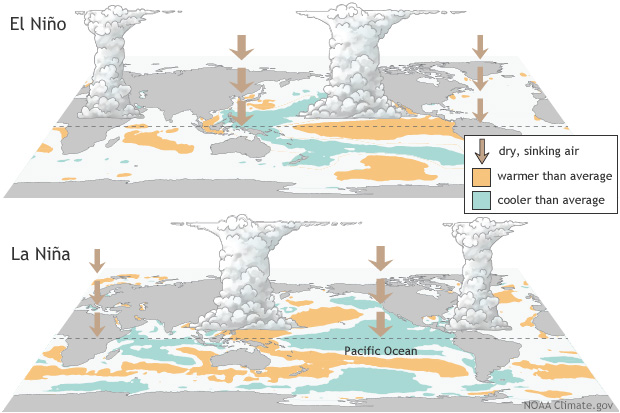

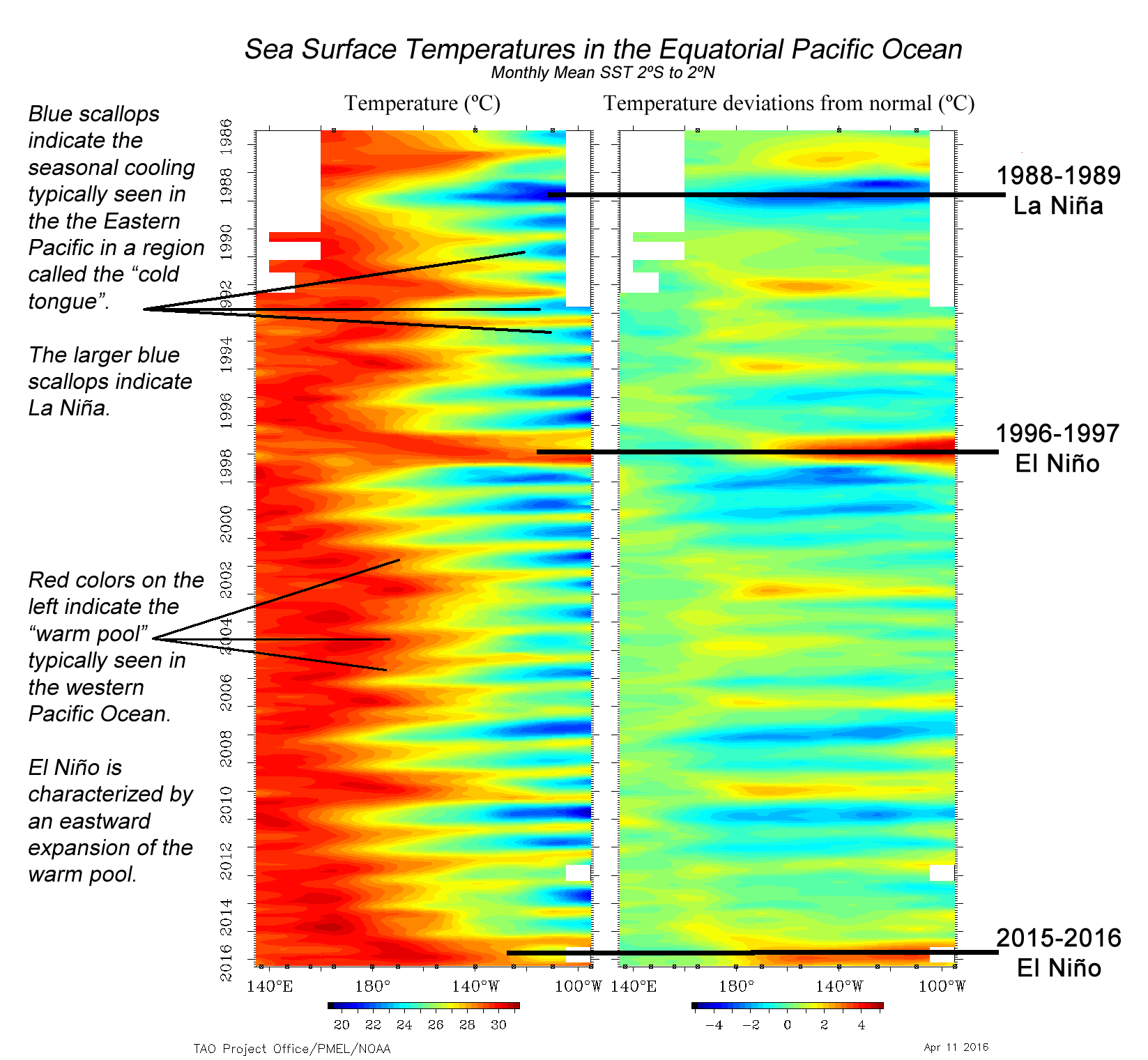

La Niña is characterized by unusually cold ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific, compared to El Niño, which is characterized by unusually warm ocean temperatures in the Equatorial Pacific. The graphic below shows the sea surface temperature in the equatorial Pacific (20ºN-20ºS, 100ºE-60ºW) from Indonesia on the left to central America on the right.

Historically, the ocean goes back and forth between El Nino and La Nina. That back-and-forth action is called ENSO by scientists. It stands for El Nino Southern Oscillation. Sometimes we are in an El Nino (more warmer water) and other times we are in a La Nina (more cooler water).

The reason one develops instead of the other is – quite – complicated so hang on tight, we are about to get nerdy…

ENSO is the result of the interaction between the surface layers of the ocean and the immediate atmosphere above it in the tropical Pacific. The internal dynamics of that relationship (the coupled ocean-atmosphere system) involving unstable air-sea interaction and planetary-scale oceanic waves determines which one, El Nino or La Nina, happen. Because the interaction is locally based, but results in global changes, forecasting the development or termination of either El Nino or La Nina is both very difficult and important.

The reasonENSO changes what the atmosphere does, and not the other way around is because this change in water temperature is not seasonally dependent. It isn’t like lake or river temperatures where it is cooler in the winter and warmer in the summer.

What is the forecast?

The forecast is that there is a greater chance that La Nina develops this Fall of Winter. Just like last year.

From NOAA:

Over the last month, equatorial sea surface temperatures (SSTs) were near-to-below average across the central and eastern Pacific Ocean [Fig. 1]. ENSO-neutral conditions were apparent in the weekly fluctuation of Niño-3.4 SST index values between -0.1°C and -0.6°C [Fig. 2]. While temperature anomalies were variable at the surface, they became increasingly negative in the sub-surface ocean [Fig. 3], due to the shoaling of the thermocline across the east-central and eastern Pacific [Fig. 4]. Though remaining mostly north of the equator, convection was suppressed over the western and central Pacific Ocean and slightly enhanced near Indonesia [Fig. 5]. The low-level trade winds were stronger than average over a small region of the far western tropical Pacific Ocean, and upper-level winds were anomalously easterly over a small area of the east-central Pacific. Overall, the ocean and atmosphere system remains consistent with ENSO-neutral.

A majority of the models in the IRI/CPC suite of Niño-3.4 predictions favor ENSO-neutral through the Northern Hemisphere 2017-18 winter [Fig. 6]. However, the most recent predictions from the NCEP Climate Forecast System (CFSv2) and the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME) indicate the formation of La Niña as soon as the Northern Hemisphere fall 2017 [Fig. 7]. Forecasters favor these predictions in part because of the recent cooling of surface and sub-surface temperature anomalies, and also because of the higher degree of forecast skill at this time of year. In summary, there is an increasing chance (~55-60%) of La Niña during the Northern Hemisphere fall and winter 2017-18 (click CPC/IRI consensus forecast for the chance of each outcome for each 3-month period).

In English? Due to NOAA scientists faith in the CFSv2 model and the NMME model, they believe that La Nina has a decent chance of development (55- to 60-percent).

What does that mean for me?

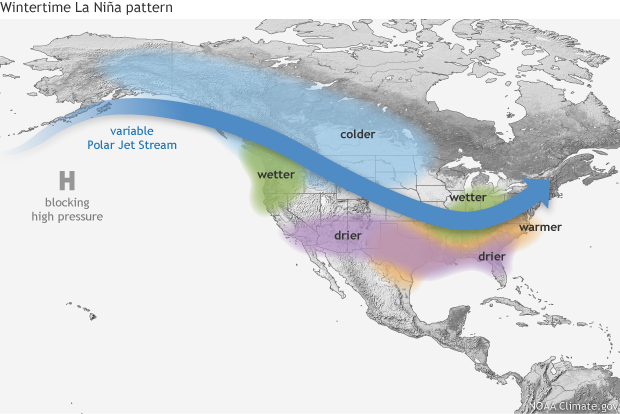

Generally a LA Nina promotes the development of severe weather across the Pine Belt. And southeast. We are generally warmer in the winter. And generally drier.

According to research by Mark Bove, “The Ohio River Valley and Deep South see a region of statistically significant increased tornadic activity during La Niña.”

The graphic to the left shows the difference between an . ENSO-neutral year (normal) and a LA Nina year (colder water). It is broken down by three-month intervals: (a) January-February-March, (b) February-March-April, (c) March-April-May, (d) April-May-June.

Notice the red blocks near us for (a), (b) but then those areas lift to our north by (c) and (d). So, despite the “generally drier than normal’ tendencies with La Nina, statistically, there is a section of the severe season that gives the Pine Belt more chances for storms, and thus, tornadoes.

That is between January and April.

Evidence for that is also supported by the historical precipitation data collected during La Nina years.

Here is a look at the forecast:

WDAM-TV 7-News, Weather, Sports-Hattiesburg, MS

Holy moly! This sounds awful!

Well, keep in mind that just like hurricanes and tornadoes – every La Nina is different. Not every one is full of doom and gloom. And with a Watch issued, it doesn’t guarantee a La Nina will develop.

And just because last winter was a La Nina, too, doesn’t mean this year will be just like last year. So, while we did have the devastating Hattiesburg-Petal tornado, and an active season, that doesn’t mean the 2017-2018 season will be the same.

If you keep an eye on the forecast and always have your NOAA Weather Radio handy and your Severe Weather Plan in place, you’ll be prepared for whatever Mother Nature can throw at us.