Every day when South Mississippi experiences storms, I head on to Facebook to search for storm reports. I look for pictures of trees down, fences knocked over, small hail, and flash flooding. Sifting through Facebook and Twitter is apart of my job now. And, thankfully some pretty gifted social media searchers have taught me how to be efficient with my searching. Because man, there is a lot of sifting to do!

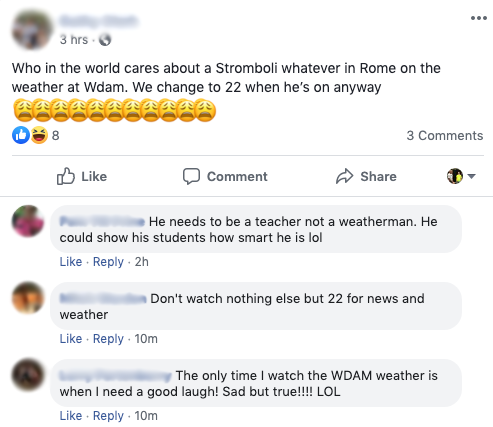

Because often times when I’m looking for storm reports, I find stuff like this:

Now, I bet these are all nice people. Seriously. I wasn’t going to blur out their names but I figured that may make it appear worse than it actually was. And this is not bad. Besides, this isn’t about any of them in particular, anyway. This is more a personal reflection how we got to this point, what I fear this type of thinking can lead to, and why we should all attempt to think about what it means for society.

As an aside: I know a lot of you will probably say to yourselves, “Don’t worry about the haters, Nick!” and never fear… I don’t. I found out back in my days on radio that most people who say, ‘I don’t like Nick because he is bad’ are the ones who watch/listen the most.

And this post isn’t about people complaining about ‘me’ but more how, as a society, we have forgotten how to be curious.

Some framing

Before I unpack all of that though, for reference, at the beginning of my 6pm weathercast one day I gave a 45-second look at the forecast for the Fourth of July and then pivoted to a quick update about an event in Italy.

It was probably a poor tactic on my part to pivot from a local weather update to Italy, but I was asked to include it in my weathercast, and I had no ‘good’ place to put it. Nevertheless, I spent 30-seconds updating the Pine Belt on a globally significant event in Earth Sciences – a volcanic eruption. One that we could see with our weather computers. These types of world events happen weekly. Sometimes it is a volcano, other times it is an earthquake, sometimes it is a hurricane, other times it is a flood or a heat wave.

But rarely can we see it with our computers!

And when big events happen, I do my best to inform viewers about earth science-related news. I figure that is part of my job as an earth scientist on a newscast.

How did we get here?

Now, back to the unpacking. I have an untested, semi-anecdotal, hypothesis that revolves around the birth and eventual ubiquity of Social Media.

The hypothesis: Perhaps we ‘got in this boat’ because, as Wesley Snipes once tweeted: “no one is posting their failures.” And since people spend an inordinate amount of time perusing social media during the day, there is a skewed understanding of reality. When no one sees “failures” anymore, failure becomes uncommon. And people become less psychologically-available to take risks, since risks often involve failure.

And if no one else ever fails, who wants to be the first one to risk failure? Some might. Others won’t.

Remember the “Around the World” game in grade school where they went around the class and you had to spell a word? Get it wrong, you’ve got to sit down. You lose.

I think Brian Regan explained it best:

There is a lot of risk there. No one wanted to be the first one to fail. But the more and more kids failed, the easier it became to be one of the kids sitting down. But, as adults, if no one visibly fails, it may be possible for people to become fearful of risks. And, it turns out, there is a lot of risk in learning.

The five risks of learning, according to Carl E Pickhardt:

1) A person risks declaring ignorance: “I don’t know.”

2) A person risks making mistakes: “I messed up.”

3) A person risks feeling stupid: “I’m not getting it.”

4) A person risks looking foolish: “This is embarrassing.”

5) A person risks being evaluated: “Suppose I fail?”

Science is about learning, not knowing

As a scientist, I am all about learning things. I love to learn.

But, if learning is risky and no one wants to take risks, that may mean no one wants to learn. The fear in society of saying “I don’t know” is pretty debilitating for some. And if no one wants to learn, where does that leave science? Because science is simply learning about things we didn’t understand by asking questions.

“As the area of your knowledge grows, so, too, does the perimeter of your ignorance.”

Think of that like looking at a circle. If you know 10 things (left), then the circumference of that circle, of the perimeter of what you can recognize that don’t know, is 11.2. But if you know 100 things (right), hen the perimeter of what you can recognize that you don’t know is is 39.4.

And if the more you learn, the more you recognize you don’t know. And people relate ‘not knowing’ with ‘risk’ then, according to Pickhardt’s list above, the very people who would benefit the most from science, are the same ones potentially most averse to accepting it.

Why? Because it involves a risk of failure and a risk of saying “I didn’t know”

Talk about a Catch 22!

It is okay to not know

Benjamin Franklin is quoted as saying, “Being ignorant is not so much a shame, as being unwilling to learn.” And when I hear about people who are unwilling to even listen to new information get presented, it pains me. Not on a personal level, but on a societal level. Because while the anti-learning folks were out there during the last 75 years, it seems that the more pervasive social media becomes, there is an decrease in the number people are interested in obtaining new information.

Or… They just don’t care, Nick

I can understand the desire to take stance, too. It has a decent shot of being right. Sometimes people are just simply disinterested in a particular topic. In the above example, perhaps the topic of volcanic eruptions is not something that interests that person.

But, I would argue, apathy is incommensurate with mockery. That is to say, that if someone doesn’t care about something, they won’t take the time to critique or poke-fun at it. So, on some level, the people commenting in the image at the top of this post do care.

I’ve never fully understood why some people have the desire for less information. Particularly when that information is free.

The term “anti-intellectualism’ is often thrown around in politics. It is, as it sounds, an aversion to learning. Outside of politics and in regular life, the same things holds true. According to a handful of scholarly articles I read while writing this piece, the idea of “anti-intellectualism” dates back about 75 years. Roughly as long as America has been making pretty incredible technological advances in some pretty small and intellectually-challenging fields. .

Curious that a rise in anti-learning occurred at a similar time as educated people started doing technologically astounding things.

This may go back to the original “Risks of learning” listed above, perhaps?

It is okay to ask questions

On a recent post about an underwater forest, I received an interesting query.

This was a fantastically packaged question from Eddy. And I think it how a lot of people feel: “Hey this is cool to know, but who cares?”

My answer boiled down to, “Discovery is its own reward with science. Because as we learn more, it allows us to ask questions we didn’t even know we were able to ask.”

And the crazy thing is, Eddy did that in his original question: “Can anybody please tell me how this research is gonna change things here on dry land.”

We would’ve had no idea that we could ask “What does a 70,000 year old stump under the ocean tell us about our climate?” But here we are.

What is your point, Nick

I don’t know. I’m trying to figure that out. I think this is more an exploration into a potential problem I see. I don’t have the solution.

But in my exploration of this topic, learning that the population of those who need to learn the most and the likely the most averse to learning was…. disheartening.

I am also curious if this is simultaneously responsible for the dramatic increase in the number of “conspiracy” ideas out there – aliens, weather control, flat earth, etc. People don’t know something, and instead of learning more and more, they are taking the first piece of information that is easiest to accept and running with it. And then those same people are at a place with an increased resistance to correcting information.

But my biggest takeaway from this would be to really encourage everyone to be open to learning new things. And learning new things about the things you thought you knew about.

Not knowing something is fine. But learning is great.