You may have seen this headline and link floating around social media recently. And before you tense up and start to worry too much, lets take a look at the article itself.

The author, Nick Shay, a Professor of Oceanography, University of Miami, takes a deep dive into the loop current, what it means and what it does. He also touches on La Nina and Climate Change, too.

It is actually a reasonably measured breakdown at all of the above topics. The article was originally posted here, and not on NOLA.com. But NOLA.com picked it up and it has been shared by a lot of people I know.

However, where it does fall short – even with Shay being a well-established researcher and expert in the field – is communicating those topics in a manner that the public can understand relative to the actual level of risk those topics present as it relates to the public and the hurricane season.

That alone is not worth shaming a researcher over, by any means. Their job isn’t to communicate these things. Their job is to understand them, completely and fully.

So, let’s take a look at the article and break out some points that I think are worth teasing out a bit more.

Let’s get Loopy

Shay writes:

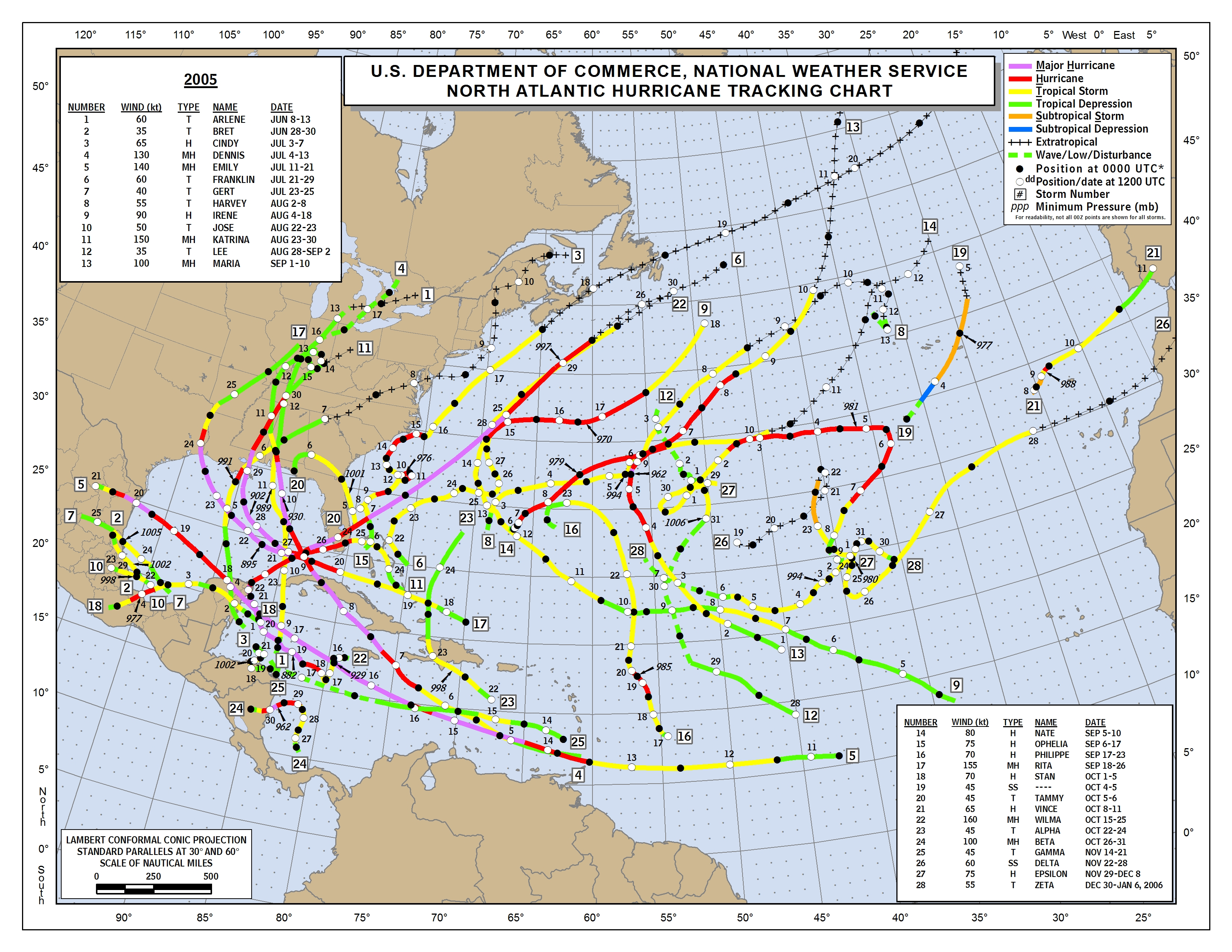

“This year, the Loop Current looks remarkably similar to the way it did in 2005, the year Hurricane Katrina crossed the Loop Current before devastating New Orleans. Of the 27 named storms that year, seven became major hurricanes. Wilma and Rita also crossed the Loop Current that year and became two of the most intense Atlantic hurricanes on record.”

I have two concerns with out this is presented. First, we have to ask, “But does it look like it did in 2005?” So, let’s look.

Understanding that our resolution of satellite data is much higher today than it was 17 years ago, you can see similarities – and differences. In 2005, it was much closer to shore, and a bit skinnier. And generally the Gulf wasn’t as warm. Nor was the northwestern Caribbean.

But, perhaps most importantly, we have to understand that while it is factual that 27 named storms occurred in 2005 – including Wilma and Rita – many of those storms never interacted with the Loop Current. As generously as I can be, only six named storms interacted, at some level, with the Loop Current.

The math on six out of 27 leaves only 20-percent. Or 1-out-of-5 named storms. And that is being generous. The named storms were Tropical Storm Arlene, Hurricane Cindy, Hurricane Dennis, Hurricane Katrina, Hurricane Rita, and Hurricane Wilma

The first three storms were heavy rain producers, while the latter three were very powerful hurricanes. So, really, 1-out-of-9 storms in 2005 interacted with the Loop Current and became devastating storms.

This isn’t to say the Loop Current cannot create bad storms. Instead, I just want to contextualize things. The author writes to give the indication that simply having the Loop Current in 2005 somehow was related to 27 named storms and seven Major Hurricanes. And sets it up with the sense of giving the reader a nudge, like, “see what can happen.” When in fact, it was only responsible for three Major Hurricanes and there were only six storms that interacted with the Loop Current that year. Not all seven Major Hurricanes, nor all 27 named storms.

We’ve seen this before…

Shay writes:

I have been monitoring ocean heat content for more than 30 years as a marine scientist. The conditions I’m seeing in the Gulf in May 2022 are cause for concern.

Sure. I get that. But where was this article last year? Or the year before? Or the year before that? Taking a look at the Loop Current the last four years, it looks like 2020 is the only year where – at this time of the year – the Loop Current wasn’t really pronounced.

And it wasn’t like 2020 had any shortage of named systems, Major Hurricanes, or landfalling tropical systems. Could the addition of a warmer, deeper, more robust Loop Current make this year worse? It could, yes. Does it mean if it weren’t there we wouldn’t be as concerned? I guess. But the one thing I learned from 2020, as a meteorologist forecasting hurricanes for only a mere 10 years, is that while one thing is bad, other things can overcome that one thing to make it worse.

Or better.

As an aside, I’ve found that over the years anyone that defends their position with “I’ve done this for “XX” years and I feel that “YY” is a thing” is a rather condescending way of saying, “I am not interesting in investigating further because I’ve already decided to feel a certain way.”

I can’t be certain if Nick Shay is doing such things, but defending a stance with “I’ve done this for a long time” is not much of a defense in Science.

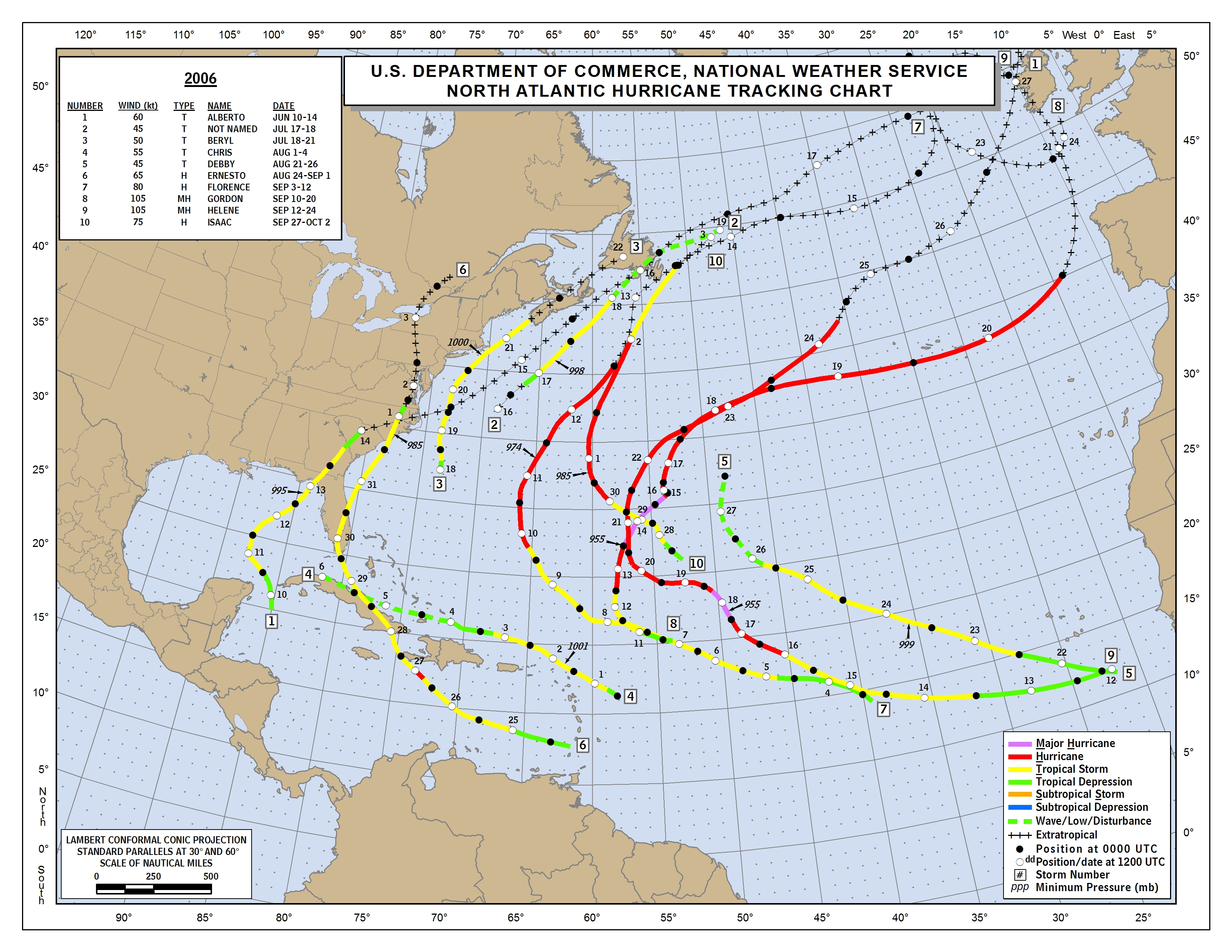

In 2006, on the heels of the epic 2005 season, many forecasters were concerned about a repeat performance from Mother Nature. “Look at the Gulf,” they said. And they were right. We were right back in the same boat.

While the Gulf was just as toasty warm and the Loop Current was similarly established, we simply didn’t see any storms develop in the Gulf. The only one was Tropical Storm Alberto.

So, to assert a fact that ‘there was a robust Loop Current in 2005’ followed up with with ‘there were 27 named storms’ and then to say, ‘there is cause for concern in 2022’ is factual, sure, but not completely transparent.

Exploding storms, except when they don’t

Shay writes:

In mid-May 2022, satellite data showed the Loop Current had water temperatures 78 F or warmer down to about 330 feet (100 meters). By summer, that heat could extend down to around 500 feet (about 150 meters).

The eddy that fueled Hurricane Ida in 2021 was over 86 F (30 C) at the surface and had heat down to about 590 feet (180 meters). With favorable atmospheric conditions, this deep reservoir of heat helped the storm explode almost overnight into a very powerful and dangerous Category 4 hurricane.

All of this is factual. But the most important part is “yadda, yadda, yadda’d” like an episode from Seinfeld.

The phrase, “With favorable atmospheric conditions” carries a lot of weight. Hurricane Ida in 2021 had a lot helping it out. It had (1) an area of upper-level low pressure to the NW to help pull the ‘exhaust’ northward ahead of the system and (2) a ridge of higher pressure guiding it along the same path as the ‘exhausting’ allowing the storm to pre-treat the environment ahead of it so it wasn’t drier. On top of that it had the Loop Current to move over and it managed to skirt all major land masses enroute to the Gulf.

So, again, to assert that, ‘Well look at Ida!’ as proof this Loop Current is bad is leaving out a lot of very important factors.

Hurricane Marco, in 2020, skid right along the Loop Current toward Louisiana. But because it slipped just to the west of the deepest most robust part of the Loop Current AND had multiple factors working against it in the atmosphere, it was a total Nothin Burger.

So, we can’t blame the Loop Current on everything.

La Nina doesn’t mean as much right now

Shay writes:

La Niña has been unusually strong in spring 2022, though it’s possible that it could weaken later in the year, allowing more wind shear toward the end of the season. For now, the upper atmosphere is doing little that would stop a hurricane from intensifying.

Again, that is factual. But man, is it incomplete. Let’s look at all of the ENSO (La Nina / EL Nino) numbers for the Spring dating back to 1999.

Some things may stick out here. The number of years that the La Nina value has been within one (1) Standard Deviation of the value this year in the Spring since 1999 sits at nine of the 13 possible years.

Take that down to half of a Standard Deviation and you get five of the available 13 years that ‘look’ like this year. That is still almost 40-percent of La Nina years. Within a quarter of a Standard Deviation, you get four years. That is about 30-percent. Nearly one-third of La Nina years have looked like this year since 1999.

Seems less “unusual” when viewed through that lens.

And the two big years 2005 and 2020? Either Neutral or barely El Nino’d.

So to say that the current state of La Nina is unusual, or to try and make ascertains that the state of a Spring La Nina is an indicator of how La Nina may impact hurricane development may be a bit of a stretch.

On top of that, the upper atmosphere IS actually doing something at this very moment and during the next week that does in fact limit the development of tropical systems over the open Atlantic and toward Africa while also allowing for more development near Central America.

The MJO is something I’ve long wanted to write a bit long post about to help everyone digest a bit better, but in very general terms it is broad areas in the atmosphere where the upper atmosphere is conducive for tropical development and not-conducive for tropical development. It is connected to more than the tropics, but very generally, for these purposes, that is what it does.

And it has nothing to do with La Nina.

The Bottom Line

This Hurricane Season is projected to be another busy year. Shay correctly pointed out, in this same article, that research suggests that Major Hurricanes may be easier to produce as our climate continues to warm. And given that, I’d recommend that if you live along the East Coast or Gulf Coast that you have a plan in place for how to respond to the chance a hurricane is pointed at you. And keep tabs on the forecast at all times this summer to make sure you know if that will happen.

And yes, this could be another year with Major Hurricanes striking the US. Or it couldn’t. Or maybe it will be like 1992 and there will be just one. And it will be big.

Seasonal forecasting isn’t at the point where we can project landfall points, specific numbers of hurricanes, or hurricane strengths. So, writing fact-based assessments of the potential consequences of certain components of a seasonal forecast is a worthwhile endeavor as it is the best we can do.

But “with great power comes great responsibility.” Writing an essay, to be consumed by the public, breaking down potentials without taking the time to shake out all of the failure points and asterisks that come along with the forecast, is, at best, an accident. Most likely lazy. And, at worst, irresponsible.

Hopefully I helped clear some things up for those who read the article, helped ease some fears of people within 100 miles of the water, and calmed the nerves of those who fight with Severe Weather Anxiety.

Headline was factual. Yes, this season may be bad. Yes, the Loop Current is robust. Yes, it even looks a bit like 2005. Yes, that could mean problems this Summer. But it isn’t a guarantee. And just because we have a robust Loop Current doesn’t mean all the other dominos are about to fall.

Words matter. Context matters. The goal was to use words to contextualize.

I’ve learned that, just like with snow, EVERYTHING has to come together for a hurricane to form and for it to strengthen to major status. When I say everything, I mean EVERYTHING. You can have warm water, both shallow and deep, a robust loop current, low sheer, and little, if any dust from Africa, but if any one of those things isn’t just right (and I mean JUST right), you may have a tropical system, but it won’t develop into anything substantial. I’m thinking that that is the point you were trying to make in your article?

Spot on!