Well, the Atlantic looks like it’s going to continue to be shut down for a while. Good news for all of us!

Last night, the NHC officially stopped warning about the system in the Gulf Coast, meaning that we currently don’t have anything forecast to develop over the next 5 days. We’ll take a look at the current state of the Atlantic, but since there are no Invests or named storms to track, we can look at what the future may hold.

Looking at the satellite imagery from last night, there really isn’t a lot to discuss, which is a nice change from the past weeks!

There is a weak system in the Gulf of Mexico, labeled with a 1, but that is not really well defined, and most of the thunderstorms associated with it are on land-which is a sign that this system will NOT be developing.

Tropical systems need thunderstorms over open ocean water in order to form, so if the forcing for storms is over land, then the process to form a tropical cyclone cannot happen.

However, since the thunderstorms are generally forming on land, this will still have impacts for coastal areas, as well as some inland areas along a front running up the Southeast.

Heavy rain is likely for many, and flash flooding is a threat for many communities, especially in Coastal AL, MS, and the Florida Panhandle. This system will not have a name, or be designated as a Tropical Storm, but it still will have impacts to people, so it’s important not to write this off.

The only thing that the Saffir Simpson scale measures is the wind. Some storms with low wind speeds or categories can cause significant impacts, so this isn’t the most important thing. It is really important to keep an eye out for heavy rain and flash flooding along the front, as this tropical moisture being lifted up has to come down somewhere.

Looking further to the East, another interesting feature is a curved band over the Bahamas and the Northern Caribbean, marked with the number 2.

On first thought, this circular system might look like something worth looking into, but the difference is that this is an upper-level system, and doesn’t have any surface “reflection”, or any low pressure at ground level.

I usually bring out this image, so now is a good time to explain this. Looking at the area where the system was at in the satellite, you would notice that there isn’t really anything in the region. For a tropical system, you would want a bright orange or red circle, and the more circular, the stronger the system is.

Really, there isn’t much bundled up vorticity at all in the Western Atlantic, so that’s why we aren’t looking at any systems developing in the next couple of days.

A little further East, and there is another area of thunderstorms off the South American Coast, with a number 3. This system is very weak, as can be seen by the above vorticity map, and is unlikely to develop.

It may move some energy into the Eastern Pacific, where storms have really been firing off, so this might be another disturbance to cross Central America and then finally form in the Pacific Ocean, well away from our interests.

Going back to the satellite image, there is one more noteworthy thing- a large cluster of thunderstorms over Western Africa. This one is labeled with a 4, and is going to be the main point of discussion for the rest of this piece.

Given that many tropical storms do form over Western Africa, it’s important to keep track of all of the tropical waves that come off the coast.

This wave is going to move to the West, so let’s take a look at some of the conditions across the Atlantic right now.

Atlantic Basin Conditions

Looking at the Sea Surface Temperatures, most of the Atlantic’s MDR (Main Development Region, stretching from Africa to the Caribbean) is warm enough to support tropical cyclone development.

Temperatures of around 26C or greater are usually required for tropical system development, and it should be right around that temperature along the potential disturbance’s track. Further South, it will encounter warmer waters that may support further development.

Looking at the Sea Surface Temperature can only tell us a little bit, and a product called OHC, or Ocean Heat Content, is a much better parameter that shows how deep the heat goes.

Looking at our current OHC, we have decent values over parts of the Atlantic, but there is a pretty sharp cutoff above 10 or 15 degrees North, so any potential system will have to take a very Southerly track.

This isn’t the best OHC, but really, anything above the dark blue is somewhat conducive.

Let’s look at another variable for storms, shear.

Currently, very strong shear exists across most of the Atlantic. This is in part due to an unfavorable upper level pattern, which is set to change in a few weeks. For the mean time, the general pattern is going to be high shear, which should suppress development.

The area which contains the African Wave has shear of 40-50 knots, which is incredibly strong, and very bad for tropical storm development. Even if all the other factors are good, this alone will kill any development. For the time being, this will definitely have a strong destructive impact on the system.

Dry air will also take it’s toll on our system of interest.

The dry air over the Atlantic is very widespread, and will also make sure that the Atlantic stays quiet. There is some moisture in the equatorial portion of the North Atlantic, but it’s weak and diffuse.

This means that the dry air will be able to infiltrate any developing system very quickly, making sure that the storms don’t strengthen much.

Big Picture

So, now that we have an idea of what’s happening right now, let’s take a look at the big picture, what’s going to happen?

Realistically, the answer is probably nothing.

It’s hard to say right now for sure, but due to very strong wind shear, and an unfavorable upper level pattern, the Atlantic is supposed to stay quiet. Whether or not a storm sneaks in, we can’t say for sure, but for at least the next week or so we should remain quiet.

There is some model support for that African wave to develop some, so I’ll show a few of the models and a potential solution.

European Ensembles showing potential development // Courtesy: Weathernerds.org

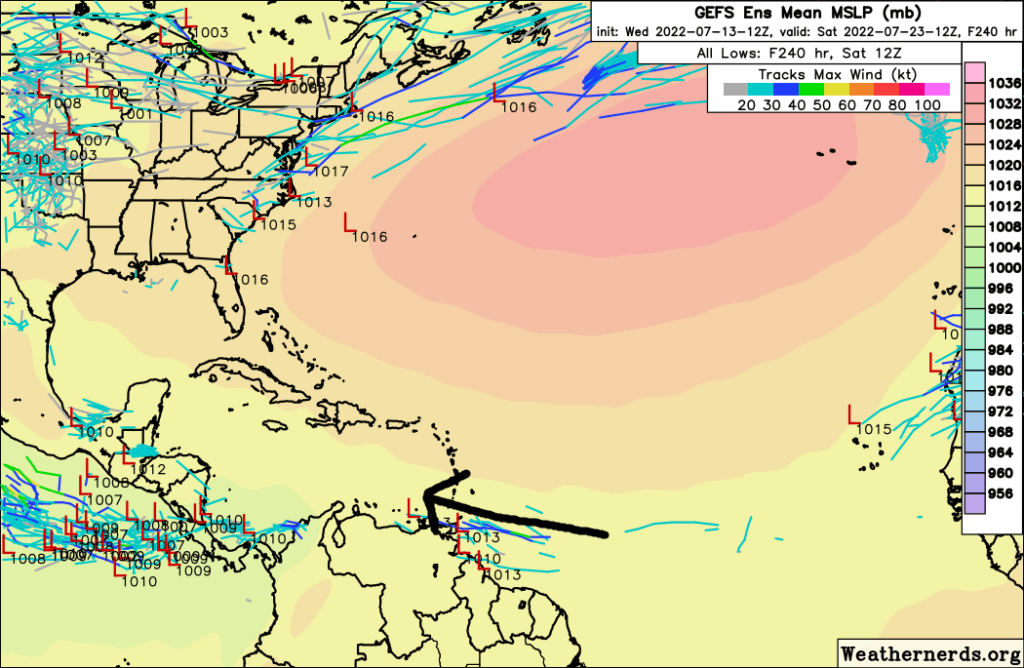

American Ensembles showing potential development // Courtesy: Weathernerds.org

Looking at both the European ensembles as well as the American ensembles, there are not very many members supporting development, making this an unlikely situation from the start. But, there are a few members forming a Tropical Depression or a weak Tropical Storm before moving it somewhere in the vicinity of the Caribbean.

More than likely, this won’t happen, and if there is a system, it will be weak and disorganized. Tropical systems cannot strengthen in such harsh wind shear.

BOTTOM LINE: There may be a weak tropical system forming in the Atlantic over the next 10 days, but it’s not likely to form and will remain weak and disorganized. Another unorganized system will bring rain to the US Gulf Coast and could cause flooding problems across the Southeast. The NHC has not highlighted any areas for concern, and the Atlantic will remain in a relative activity lull.