Good morning, folks, and happy Wednesday! In the Tropical Outlook today, we’ll review the current conditions in the Atlantic Basin and then we’ll take a look at the large-scale patterns and model data to see what the future will hold.

Current Weather in the Tropics

At the moment, the National Hurricane Center is not watching any systems for their potential to develop into tropical cyclones within the next five days. This has been the story for much of the season, as the Atlantic has remained largely unfavorable for tropical cyclogenesis thus far.

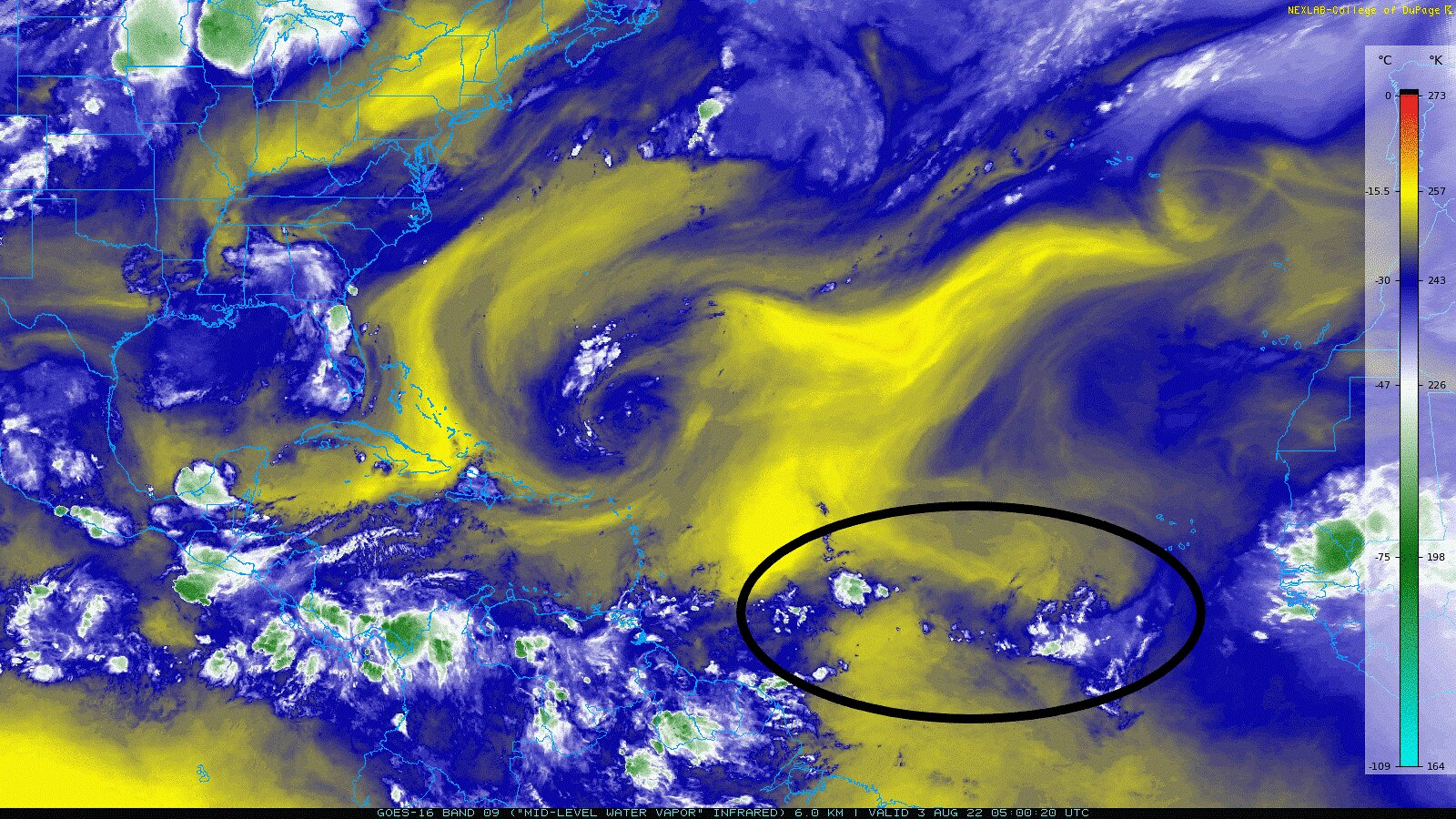

If we take a look at the region Sincere highlighted in the last Tropical Outlook, we can see that the cloud tops are not nearly as high as they were yesterday, which tells us that the thunderstorm activity associated with the disturbances in this region has fizzled out.

Regardless of the lack of convection in the Main Development Region (MDR) over the Tropical North Atlantic at the moment, there is a large burst of convection associated with an emerging African Easterly Wave currently over West Africa.

One reason why these disturbances in the MDR are struggling to produce consistent thunderstorm activity is due to the very large region of dry air currently in the North Atlantic. While both the regions to the north and south of the intertropical convergence zone (ITCZ) – the region where our limited convection is – are typically dry, the ITCZ itself is unusually dry, as well.

This is significant because any thunderstorms that may fire up in this region will entrain drier air into the storm’s downdraft; this drier air will result in much more rain evaporating before it reaches the surface than usual – a process that cools the air, making it more dense. This blob of cooler air is called a cold pool, and as it is more dense than the air around it, it will sink toward the surface and spread out radially from the storm. As a result, the storm’s updraft – the energy source of the storm – will be undercut by the more dense cold pool, and the storm will weaken. Even though storms can still develop due to the moist air at the surface, they don’t tend to stick around due to the drier air aloft, hence why drier mid-levels are unfavorable for tropical cyclogenesis.

Beside the strikingly noticeable swath of dry air in the Atlantic, the water vapor imagery also shows draws our attention to a few swirls in the Basin, including an upper-level low northeast of Puerto Rico, which is producing some fairly isolated and weak convection in the open waters between Puerto Rico and Bermuda.

One of the other important conditions necessary for tropical cyclogenesis is wind shear. According to the GFS model-output wind shear as of the time of writing, the shear around the ITCZ looks to be on the low side. However, the shear does remain high across much of the Caribbean and east of the Lesser Antilles, largely in part to the influence the aforementioned upper-level low has on the region…

What the Future Holds

While things certainly don’t look favorable for development at the moment in the North Atlantic, Hurricane Season does begin to ramp up in the month of August, especially as we head further into the month. As the main deterrent to tropical cyclogenesis is the lack of moisture, it’s important to watch the progress of the African Easterly Waves (AEWs) emerging into the MDR as they provide critical moisture transport to the region.

While it does take some time, going into late next week the European model has a constant stream of disturbances flowing off of West Africa, saturating the mid- and upper-levels of the atmosphere. This particular solution shows a disturbance a few hundred miles east of the Lesser Antilles trying to develop, but likely struggling due to some more dry air to the north, and enhanced wind shear courtesy of the interactions between an upper-level ridge (also known as a TUTT low), and the sub-tropical high.

The GFS solution, on the other hand, shows a narrower corridor of moist air along the ITCZ, but overall less wind shear due to a weaker TUTT low – sub-tropical high interaction. It is important to note though that the ECMWF and GFS solutions yield very different outcomes as the forecast time is over 200 hours out.

Conclusions

While the Atlantic is Quiet at the moment, and looks to stay relatively quiet through next week, activity in the Atlantic does typically begin to ramp up this time of year, so it is very important to continue to monitor the tropics as conditions in the North Atlantic become more favorable for tropical cyclogenesis.