JUNE 26, 2019 UPDATE:

Bonnet Carre closure to begin at a stage of 15.5 feet at Carrollton Gage. This will allow crews to safely close bays. Based on forecast from NSW closing process could start 2nd or 3rd week of July. #2019floodfight @MVD_USACE pic.twitter.com/kLL9Xj1wfd

— Corps of Engineers (@TeamNewOrleans) June 26, 2019

The Bonnet Carre spillway closure will not impact the dead zone, however it may help the coastal waters of Mississippi.

ORIGINAL:

Bad news for marine wildlife and fisherman: NOAA scientists are forecasting a hypoxic (dead) zone of 7,829 square miles this summer.

That is an area roughly the size of Massachusetts. And larger than last year’s forecast by about 2,000 square miles

What is it?

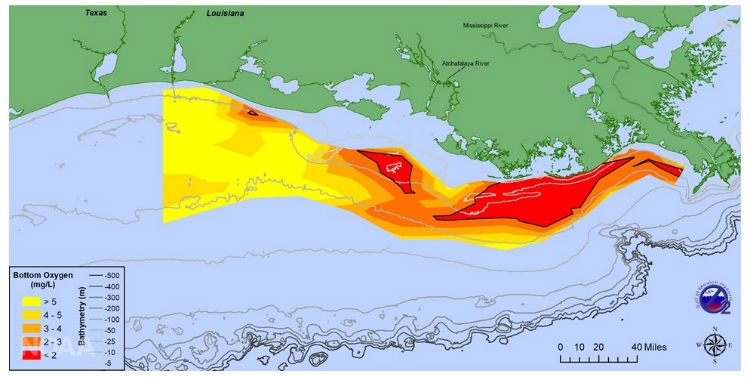

The dead zone is an area where marine life cannot survive due to a lack of oxygen. The lack of oxygen is because of blooms of microbes and fertilizer runoff. The zone “occurs between the inner and mid-continental shelf in the northern Gulf of Mexico, beginning at the Mississippi River delta and extending westward to the upper Texas coast” according to serc.carleton.edu.

From EPA.GOV:

Hypoxia means low oxygen and is primarily a problem for estuaries and coastal waters. Hypoxic waters have dissolved oxygen concentrations of less than 2-3 mg/L. Hypoxia can be caused by a variety of factors, including excess nutrients, primarily nitrogen and phosphorus, and waterbody stratification (layering) due to saline or temperature gradients. These excess nutrients can promote algal overgrowth and lead to eutrophication. As dead algae decompose, oxygen is consumed in the process, resulting in low levels of oxygen in the water.

These hypoxic zones aren’t as bad for adult fish – since they can just swim away – as it is for crustaceans, shellfish and younger fish. The less-mobile aquatic species, the ones that aren’t adult fish, can’t move fast enough to leave one of these hypoxic zones and they simply suffocate and die. This can have dramatic and last impacts on an ecosystem of the area of dead less-mobile aquatic species is large enough.

It can also take a toll on the fishing economy.

The annual prediction is based on U.S. Geological Survey river flow and nutrient data.

How bad is this one?

The record was set in 2017, when nearly 9,000 square miles was hypoxic. Last year, officially the hypoxic zone was only about 3,000 square miles. The 2018 hypoxic zone may have been impacted by persistently strong westerly winds and waves that likely led to enhanced mixing conditions and smaller-than-expected zone size, according to researchers.

Given all of the excessive rainfall along the Mississippi River watershed, there is abundant excess sediment running into the Gulf. So, this year’s is somewhere toward the bad end of “how bad” unfortunately. I doesn’t look like it will be a record, but it will be high.

The forecast isn’t always easy, since the Gulf of Mexico hypoxic zone can be dictated by short-term weather phenomena. The NOAA researchers are leaning on those models, though, for accuracy.

“The models help predict how hypoxia in the Gulf of Mexico is linked to nutrient inputs coming from throughout the Mississippi River Basin,” said Steve Thur, Ph.D., director of NOAA’s National Centers for Coastal Ocean Science said in a statement. “This year’s historic and sustained river flows will test the accuracy of these models in extreme conditions, which are likely to occur more frequently in the future according to the latest National Climate Assessment. The assessment predicts an increase in the frequency of very heavy precipitation events in the Midwest, Great Plains, and Southeast regions, which would impact nutrient input to the northern Gulf of Mexico and the size of the hypoxic zone.”

NOAA states that sediment deposition into the Gulf of Mexico varies by year, due to changes in precipitation. So, USGS monitors the longer-term changes in nitrate and phosphorus loading into the Gulf of Mexico from the Mississippi River.

“Long-term monitoring of the country’s streams and rivers by the USGS has shown that while nitrogen loading into some other coastal estuaries has been decreasing, that is not the case in the Gulf of Mexico,” said Don Cline, associate director for the USGS Water Resources Mission Area said in a statement. “USGS monitoring and real-time sensors, coupled with watershed modeling, will continue to improve our understanding of the causes of these changes and the role they play in the Gulf and other coastal areas.”

What is causing it?

Keep in mind this hypoxic zone is, in general, a naturally-occurring phenomenon. The size and breadth of the hypoxic zone is the part that humans contribute to and is the part that fluctuates. For example, there are at least 500 dead zones that have been reported near coastal areas in recent years, up from fewer than 50 in 1950.

But some were always around. IT just wasn’t as bad historically.

The increase in hypoxic zones is likely due to agriculture and urbanization. Runoff from both end up in the oceans and, as stated above, can lead to blooms of algae, and thus microbes, that eventually pull the oxygen out of the water.