The headline says it all. Looking back at 70 years of data, South Mississippi’s hottest days during the “Summer” (from May through September) have stayed about the same while the temperatures overnight have warmed up considerably.

Mathematically speaking if you look at the last 35 years versus the previous 35 years, there is an equal chance that you find a 100-degree day – or warmer. Over that same time period you are four times more likely to find a warm night between 1985 and 2019 than 1950 to 1984.

The Data

Let’s start with a look at afternoon high temperatures.

Afternoon Highs

| Total years | ’50 – ‘84 | ’85 – ‘19 | |

| 100 degrees that year | 28 | 13 | 15 |

| Total Years | 70 | 35 | 35 |

| 40.00% | 37.14% | 42.86% |

The table above breaks down how many years featured a 100-degree-or-warmer day. In total, 40-percent of the years between 1950 and 2019 featured at least one day with a 100-degree (or warmer) reading. While seeing a five-percent increase may feel substantial, I’m not to impressed given the small sample-size. South Mississippi has only had two more years with 100-degree-or-warmer readings. That isn’t a “big” deal to me.

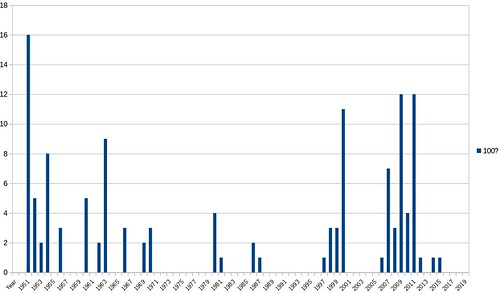

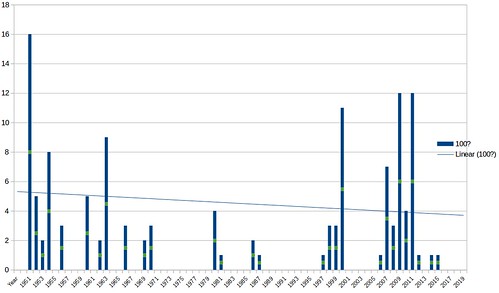

Graphically speaking, the data looks like this when broken down by ‘How many days per year are 100-degrees or warmer’

That looks like a dumbbell, almost. weighted at both ends.

Put a trend line on there and the trend of the number of days with 100-degrees or warmer has actually decreased since 1950! That is likely due to the erroneously warm summer of 1951, but hey, that is apart of the record book. So it is going to skew the line.

Overnight Lows

Overnight lows? That is a completely different story.

| Total Years | ’50 – ‘84 | ’85 – ‘19 | |

| 76-degree-or-warmer | 57 | 23 | 34 |

| Total Years | 70 | 35 | 35 |

| 81.43% | 65.71% | 97.14% |

Between 1950 and 1984 there were 23 years that featured at least one night of 76-degrees-or-warmer. From 1985 through 2019 there were 34. The only year between 1985 and 2019 that didn’t have a 76-degree night? 1997.

That means that every year for the past 23 years there has been at least one night that it was at least 76-degrees.

Prior to 1984 that only happened two-out-of-every-three years. That is a pretty decent increase.

Graphically speaking, it is even more evident. Particularly when you look to see how many days per year there are lows 76-degree or warmer.

That graph looks pretty lopsided. Add in a trend line and it is even more evident!

So we know that what used to happen one-night-per-year on two-out-of-every-three-years is now happening every year, but how often does it happen per year? On average, a 76-degree-or-warmer-night happens nine times per year. Here is a look at that, graphically.

That is a pretty decent increase, too.

Taking it one step further. Of the possible 5355 days during the Summer months, only 55 featured a temperature at 76-degrees or warmer between 1950 and 1984.

Of the possible 5355 days between 1985 and 2019, there were 234.

A more-than four-fold increase!

So much for sleeping with the windows open, I suppose!

Why are nights getting warmer, but not daytime temperatures?

That answer can be sort of complicated… But let’s break it down. It starts with greenhouse gasses. And not always the human-burned kind, either.

Water is a greenhouse gas! Good ole H2O does a great job at trapping heat.

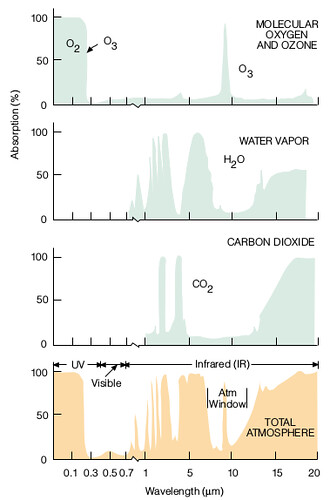

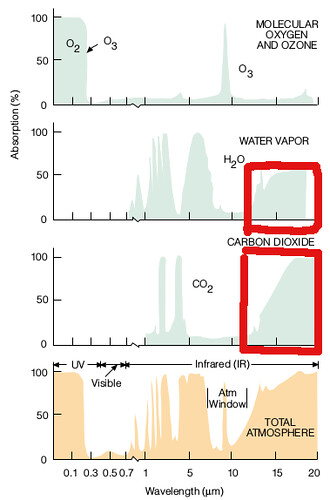

The heat that is trapped is actually via infrared radiation (not the kind of radiation that give you super powers, sorry). What happens is during the day is that the suns energy is being absorbed all day long by everything. At night, that heat is released via longwave infrared radiation.

And certain molecules in the atmosphere absorb that radiation, and heat up.

Looking at the graphic below, notice that while water is pretty good at absorbing the longer wavelengths (the right-hand side of the chart), Carbon Dioxide (CO2) is way better.

And, sadly, we have been putting more and more CO2 into the air.

A brief break for an analogy

If you went out fishing with a normal fishing pole and a mixture of bait and lures (live worms, spinners, soft plastic baits, and flies) and every day you only caught one fish. That’d be great! No complaints, right?

But what if I gave you two poles? You could catch more fish! Same bait and lures. Just now instead of them sitting in your tackle box, they can be used. All at the same time. Now, what if you had five poles? Or a dozen?

That’s a lot of fish!

Human-caused climate change is like fishing with extra poles

All of the Carbon that used to be locked up in the ground as, say, coal and oil, has now been burned and turned into Carbon Dioxide (CO2). And when it is warmer, it is easier to evaporate more water, leaving more water vapor in the air.

We have, in essence, increased the number of fishing poles we can use to catch fish. Only difference is instead of bait and lures, it is molecules of greenhouse gases. And instead of fish, we are catching longwave radiation.

And the biggest difference is when you’re fishing some days the fish just aren’t biting. But when it comes to atmospheric chemistry, the molecules are always trapping longwave radiation.

Okay, back to explaining the 100-degree days with… Chemistry?

Totally. The phrase “Better living through chemistry” should be on a shirt. Chemistry can explain a lot. I would say, it can even explain the relative lack-of-change in the number of 100-degree days.

We have to talk about Specific Heat. The Specific Heat of a substance is the amount of heat needed to raise the temperature of one gram of that substance by one degree Celsius. And water has a high Specific Heat. That means it take a lot of energy to change the temperature of water.

And water vapor.

So air that is moist tends to hold its temperature better than air that is dry.

That means that during the Summer when it is really muggy down in South Mississippi, it is less likely to be 100-degrees than when it isn’t as muggy

And it is more likely to be muggy if the air temperature is warmer overnight. Because the higher the temperature, the easier it is to evaporate water and hold it as water vapor.

Wrapping it up

So, you can think of it like this. Warmer nights are warmer because more molecules are soaking up that longwave radiation trying to escape from Earth after a long hot Summer day. That now-warmer air can ‘hold’ more moisture. And, because it is warmer, it can evaporate more water, too.

So, it may be more humid overnight.

And when it is more humid, it is more difficult to change the temperature of the air the following day. That may hold the temperature down from reaching 100 or more. And it may only be 99.

But that creates a new problem: Heat Index. But that that has already been covered here, I suppose.

What can we do to change this?

There are so many ways! Recycle! Drive less! Diminish your ‘carbon footprint’ as much as possible. It doesn’t have to be drastic, because every little bit helps.

Sure, drastic measures are probably necessary to curb it completely. But, I also understand a lot of people are resistant to big changes to their habits – regardless of how dire the situation is. We are all used to driving our cars, burning coal for electricity, and using plastic bags. It is hard to change that overnight.

Another analogy? Sure! It is like when your doctor tells you that something you’re doing is slowly killing you (think like smoking, drinking, or eating fatty foods). You don’t feel like you are dying right now, so why change? But, a lot of times the damage you are doing to yourself by eating fried foods (and I’m just as guilty of this as the next person) isn’t as evident to the naked eye.

The only difference is that we are – in a way – killing our planet. And while it may not feel like we are killing it. That is only because the damage we are doing can’t be seen or touched. We can’t point to a rock and say, “There it is, there is the climate changing!”

So we have to look at things that are a result of the climate changing (extinctions, water temperatures, air temperatures, atmospheric composition) and measure that.

Just know that the less carbon we put into the air, the better. That way all of the longwave radiation can just escape to the atmosphere with no problem. And it won’t get ‘caught’ by the extra CO2 or the extra water vapor.