When trying to find out how gross it is going to feel on a hot summer day, meteorologists often cite the “Heat Index” for a more accurate portrayal of what it may actually feel like as you step out the door. Some meteorologists – myself included – have been encouraged to change the name on air to the “Feels like” temperature. That way, everyone watching understands the meaning of the number.

But just how muggy is it? And why? And what the heck is a dew point?!

To understand why it feels worse on days with more moisture in the air, we have to go back to school for a minute…

The Dewpoint

Dew point is pretty straight-forward once you widdle it down: The dew point is the air temperature that water vapor condenses out to form liquid water. The higher the temperature, the more water vapor. Sp, a low dew point is dry and a high dew point is considered moist. But there is a cool nugget of info that falls out of this.

Here is an analogy: Imagine you had a one-gallon bucket. And you had two gallons of water. If you tried to pour all two gallons of water into that one-gallon bucket it would

overflow, right? Getting the floor all wet. The one-gallon bucket doesn’t have enough volume to hold that much water. You would need to increase the volume of the bucket in order to hold all two gallons, right?

Anything extra would just end up as water on the floor.

The same principle applies to dew point in the air. It turns out that the dew point temperature cannot be higher than the air temperature. Why not? Well, if all the sudden the dew point were higher than the temperature, then all of the water would condense out instantaneously. It would “overflow” from the atmosphere and spill out.

This also means that Homer was sort of on to something here…

The air isn’t “filled” with water until it “spilled” out as fog or clouds. When that happens it is called being saturated.

And how about this! There is another cool nugget that falls out of that! If you want to saturate the air, you can either pump more moisture into it… or simply cool the air temperature down.

As an example, this of an air temperature of 80 degrees and the dew point temperature is 60 degrees… you can get to saturation two ways. You can either increase the amount of moisture to increase the dew point to 80 degrees. Or you can cool the air temperature down to 60 degrees.

Relative Humidity

Turns out that the term “relative” here is very important. The relative humidity calculates the amount of moisture in the air relative to the current temperature. But it isn’t as simple as just dew point / temperature.

To figure out the relative humidity, you have to solve this equations:

=100*(EXP((17.625*dew point)/(243.04+dew point))/EXP((17.625*temperature)/(243.04+temperature)))

That means that for the above example of a temperature of 80 and a dew point of 60, the relative humidity is about 51 percent. And, in fact, a temperature of 90 and a dew point of 69 gives you the same humidity value. As does a 100 degree air temperature and a dew point of 78.

Uh oh. We may run into a problem. Because, as it gets warmer the “relative” part of relative humidity is increasing the amount of moisture that is in the air. So as the temperature increases the more muggy it will feel.

Because if we cooled the 100 back down to 78, we would reach saturation. Cool the 80 down to 78, and nothing – noticeable – changes.

If attempting to figure out the Heat Index, using relative humidity means for the first example of 80 degrees with a relative humidity of 51 percent, the heat index is 81 degrees.

The second example – 90 degrees with a 51-percent humidity – it would feel like 96 degrees. The third? It would feel like 119!

So, for different temperatures, because relative humidity is dependent on the air temperature, it isn’t a great indicator for heat index nor of just how humid it may feel.

Plus, as we found out above, a dew point of 78 has way more moisture than a dew point of 60.

Back to Heat Index

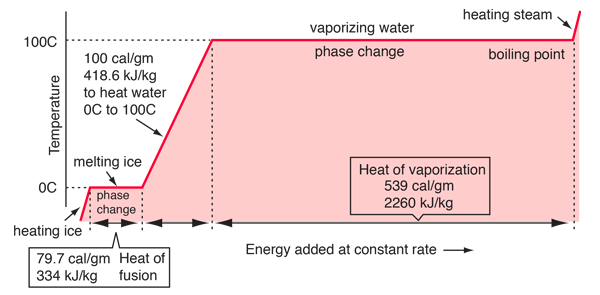

Our bodies are heat engines. We sweat to cool ourselves down. Because it takes energy to evaporate water.

How much energy? Well, that depends on how much water. And we can get into the weeds of mathematices pretty fast, too. Suffice to say, given the high Specific Heat of water (meaning it likes to stay the temperature that it is at, so it takes a lot of energy to warm it up) you need to do a lot of work to get it to evaporate.

But something really cool happens when it does. Literally cool.

When energy is used to evaporate water, as it evaporates, it takes that energy with it. And since our bodies are heat engines, and we sweat, the evaporating sweat is taking the heat with it as it evaporates. In turn, cooling you down. Because the evaporating water took the heat you used to evaporate it.. with it!

Now, on days where there is very little moisture in the air, there is plenty of space to fill in the atmosphere with your sweat. You can go for a jog, heat the water up, and it evaporates away, taking the heat with it. And you feel nice and cool!

But what happens when there is more moisture in the air? There isn’t as much space to put your evaporating sweat. So it stays as liquid. If it is still a liquid, it is sitting on your skin with all of that heat energy locked up inside it with nowhere to go.

And you stay hot.

Even though the relative humidity was only 51 percent. The same relative humidity at 80 degrees, that would have allowed you to go for a jog, no problem.

Wrapping it up!

So, because we found out that the dew point is the actual measurement of moisture in the air and the relative humidity is, just that, relative. We now know that to figure out if it feels muggy or not, we need to know the dew point and not the relative humidity.

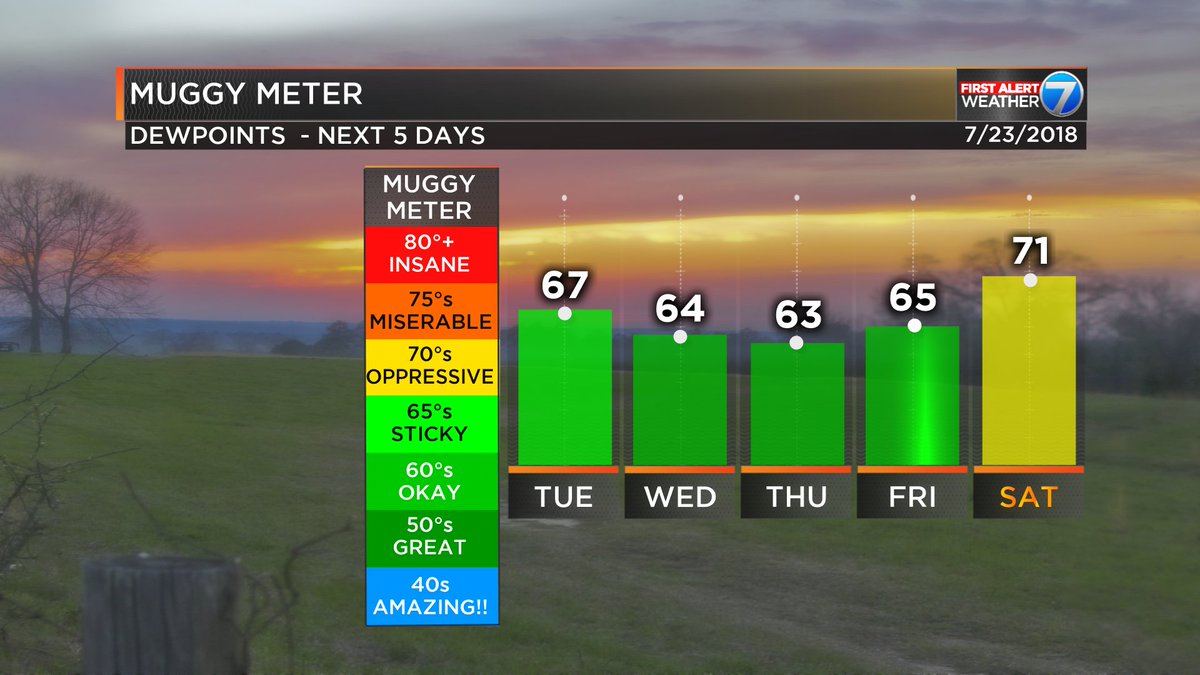

So what dew point numbers mean what? Well at WDAM we came up with a handy guide earlier this summer. Here is a look at one graphic we use on the air. This one is from back in July: