Often times during winter events you might hear your TV weatherperson talk about a “deepening cold air” or “Cooling the atmosphere” in order to get snow to fall rather than rain, freezing rain, or sleet. While cold air in the atmosphere above us isn’t a guarantee for snow, it does help with “build” snowflakes.

The types of snowflakes you see in the air while you’re out trying to catch them on your tongue are based on a few different factors, but the main one is the “dendritic growth zone.”

Note: Because meteorologists and atmospheric scientists like to look at the atmosphere in terms of pressure (900mb, 800mb, 700mb) and not height (1,000ft, 2,000ft, 3,000ft), I’ll try to add a conversion every time I mention one or the other. Also remember that meteorologists and atmospheric scientists count backwards relative to height, so for 800mb is closer to the ground than 600mb.

The dendritic growth zone, or DGZ, is the zone in the atmosphere where snowflakes are made. It is often between, roughly, 10-below-zero and 20-below-zero Celsius. Snow forecasting purists may argue it is closer to 13-below and 19-below, but for our pruposes, -10 to -20 will work.

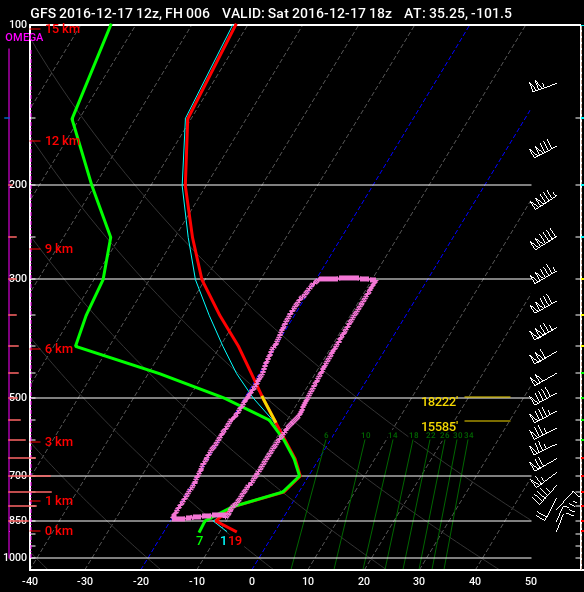

Take a look at the forecast sounding below.

Want more info on reading one of these charts? Check this out!

This is from the GFS computer weather model for Amarillo, Texas back in 2016. This sounding shows the temperature and the dewpoint from the surface, all the way up to 200mb (38,000ft).

The highlighted area is the dendritic growth zone. Where the two temperature and dewpoint lines move through this area is where you can see snowflake development. And, depending on how much moisture is available (by looking at the dewpoint), the vapor pressure, and the wind speeds, you can “build” many different kinds of flakes (for more information on building snowflakes, check this out).

The zone in the above graphic there is a small zone around 850mb. But really, the DGZ is between about 600mb (14,000ft) and 500mb (18,000ft). And notice that the temperature and the dewpoint line are very close together. That tells us the atmosphere is close to saturated in the DGZ. In fact, it is saturated at just below the DGZ from 800mb (8,000ft) to 600mb (14,000ft) which mixed with some decent vertical velocity could mean even more snow (but that discussion is for another day)!

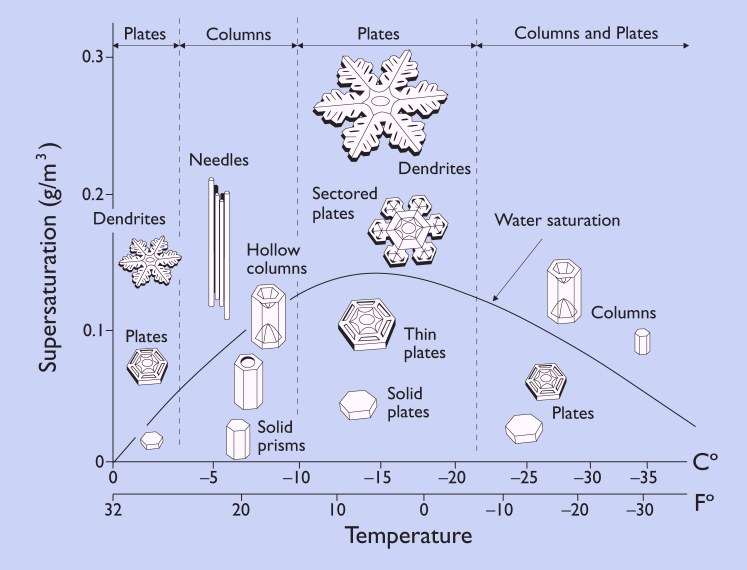

So, given the near-saturation status, take a look at the graphic below and notice we can expect smaller plates to grow rather than big fluffy snowflakes.

So we’ve now established where the dendritic growth zone is – between -10 and -20 celsius – and that we need to be very close to or at saturation to get a certain type of snowflake to form. Great! But let’s get back to what those snowflakes look like at the surface, where we are with our tongues out trying to catch a few.

Okay, look closely at the sounding again.

Notice the temperature between where the snowflakes are being made and the surface (bottom of the graph) is well below freezing. That means if any snow falls, it won’t melt while it falls toward the ground and will fall as snow.

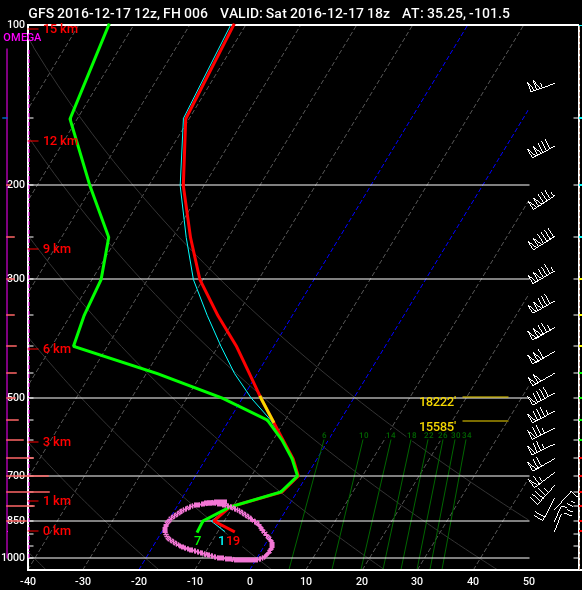

But it isn’t always that easy. Here is a look at another sounding. This one has the Dendritic Growth Zone up around 17,000 to 20,000ft (around 500mb). But there is a big part of the atmosphere, between 700mb and about 900mb that is above freezing.

So any snowflake that is built, would be melted before it got to the ground. And, in this case, because the temperature at the ground, and just above it, is below freezing, this is likely freezing rain.

To get sleet, there needs to be a smaller above-freezing layer sandwiched between two below-freezing layers, like in the sounding below.

Here, we are still making snowflakes up around 16,500 to 19,000ft, but they are melting and then re-freezing to form sleet.