I wanted to take a moment to clear the air about something that really resonated with some folks.

I said last week that Harvey was not going to blow up, rapidly intensify, and take a hard turn toward South Mississippi, like Hurricane Katrina. As we all know now, it did rapidly intensify. The forecast was only half right.

The Goal: Let people in South Mississippi know we were not in danger.

The Result: Mixed. At best.

Some have chosen to try to “rub my nose” in this. Or tell me that I’m a moron. And that’s rude. But expected. This likely won’t resonate with those people.

For those who aren’t interested in cheap-shots at your local meteorologist, but are curious about just what the heck happened, I want to really break this down explaining my rationale, thought-process and decision-making during the forecast period, as well as what I’ve learned from it.

And how while the forecast didn’t pan out, I’m more disappointed in my messaging than in my forecast.

The Messaging Problem

1. I probably shouldn’t have explained it the way I did. That was wrong. There is always a possibility for something in weather. Even when it is, like, a 0.002 percent, there is still “a chance” that it happens.

The toughest part about predicting the weather is turning a world of probabilities into not-probabilities as most people just want to know “will it rain or won’t it?”

Well, in all transparency, forecasting really can’t answer that question. We can only tell you how great the chance is that rain may occur. Sure, sometimes that chance is infinitely small. Others it is infinitely great. That’s easy. But when it is not, our job is to try to convert a probability into something that is concrete.

And saying this “won’t happen” or “will happen” is often the word choice we use. Even though there is still a chance for the opposite.

With the Tropics and Severe Weather, I always try to give the probability as well as a best-case or worst-case scenarios.

This time, I didn’t do that. Why? I’ll answer that with number two.

2. I have a phone call / email exchange / social media message / in-person conversation every day during hurricane season comparing a current or possible threat to Hurricane Katrina. There are multiple different types of messages, but most fit within the theme of: “XXX storm looks just like Katrina” asking if we need to watch out for it.

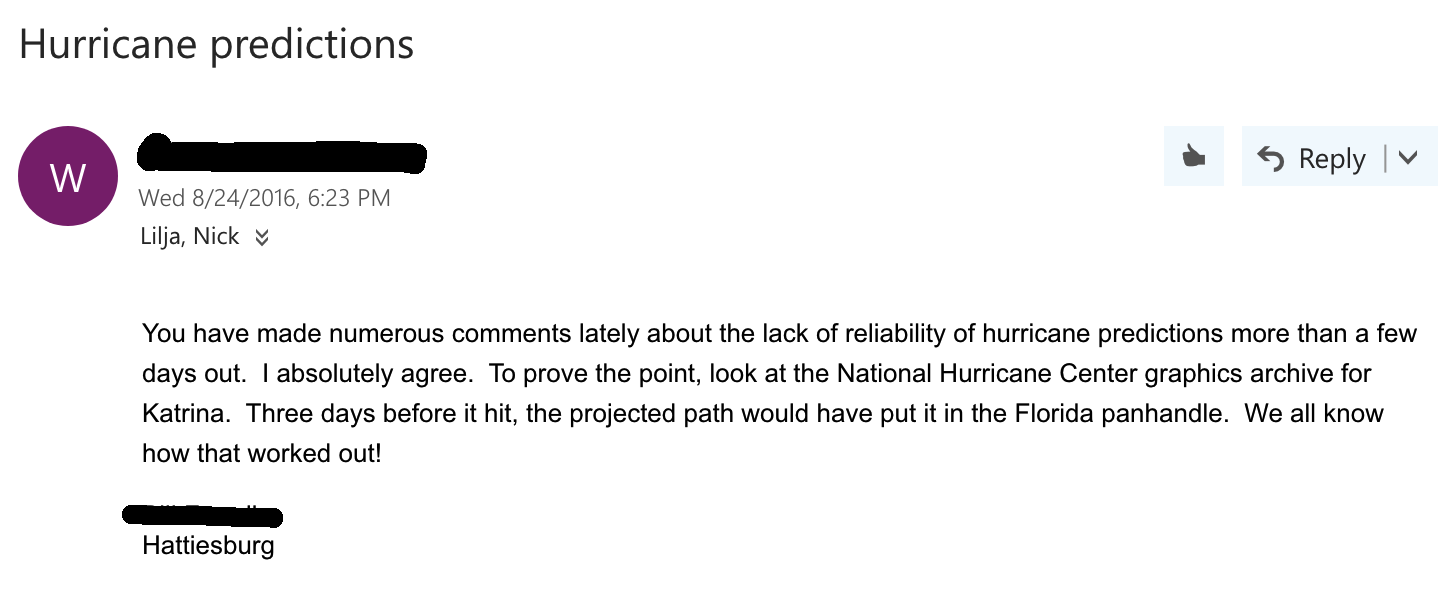

Over time, that has changed the way I talk about tropical weather forecasts. No matter how many times I explain how the forecast for Katrina wasn’t as bad as people remember, it doesn’t resonate. Perhaps making me too biased and sensitive to people’s fear of Katrina.

Since 2014, I have had to explain that (2014) Arthur, TD Two, Bertha, Cristobal, Dolly, Edouard, Fay, Gonzalo, Hanna, (2015) Ana, Bill, Claudette, Danny, Erika, Fred, Grace, Henri, TD Nine, Ida, Joaquin, Kate, (2016) Bonnie, Colin, Danielle, Earl, Fiona, Gaston, TD Eight, Hermine, Ian, Julia, Karl, Lisa, Matthew, Nicole, and Otto (2017) Arlene, Bret, Cindy, TD Four, Don, Emily, Gert and Harvey are not going to rapidly intensify and move toward us. That is 43 different storms. Not to mention the countless number of Invests, too.

I spend a lot of time helping folks rest a bit easier telling them “this isn’t going to be like Katrina” since people – rightfully – worry about that. And based on the interactions I have with folks, they worry about it, a lot. And that’s fine. And probably good. It helps people stay prepared and on-guard for the next major storm.

My message of “this won’t be like Katrina” held for 43-consecutive storms – over a 1,000 day period. The message was relayed, understood, and lowered stress. It was a success.

This time, on the 44th time, the message was the same and but the forecast was half-right. Because of that, I re-learned something about how people perceive information.

And why perception is so important: Perception is sometimes reality.

3. I’ve always understood that viewers only retain bits and pieces of a forecast. I learned, may moons ago, that if you want someone to really digest the information you are presenting you have to say it three times. Not just once. And the message needs to be clear and concise – all three times. Not just once. And it needs to have evidence to back up the forecast. All three times. Not just once.

So, when I said, “Harvey is not going to rapidly intensify, and take a hard turn toward South Mississippi.” the message, on the surface, was clear and concise: “South Mississippi is not in danger.” But I only said it once. And I didn’t fully explain the reasoning, either. And I didn’t do either three times.

What some people took for it was “Nick said it won’t be like Katrina” and didn’t remember the rest. And that is my fault, not theirs. I didn’t take the time to really spell out what the most important piece of information was: It isn’t coming to South Mississippi.

The real message was “We are not in danger.”

The Intensity Forecast

Before I get into this, please know that the track, impact forecast, and, eventually, the intensity forecast for this storm were well forecast. Serious kudos to the NHC. From the time that Harvey crossed over the Yucatan, most everyone was concerned about a long-term flooding event for south Texas with 15″ to 40″ of rain possible. This discussion is about the intensity model forecast data of the storm from August 22nd through the 24th.

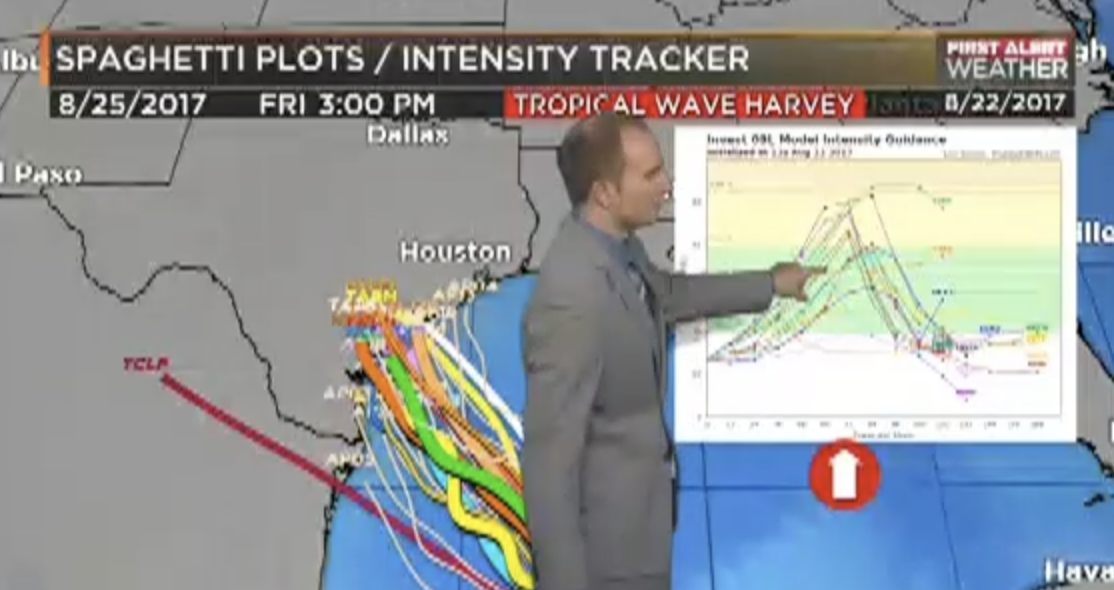

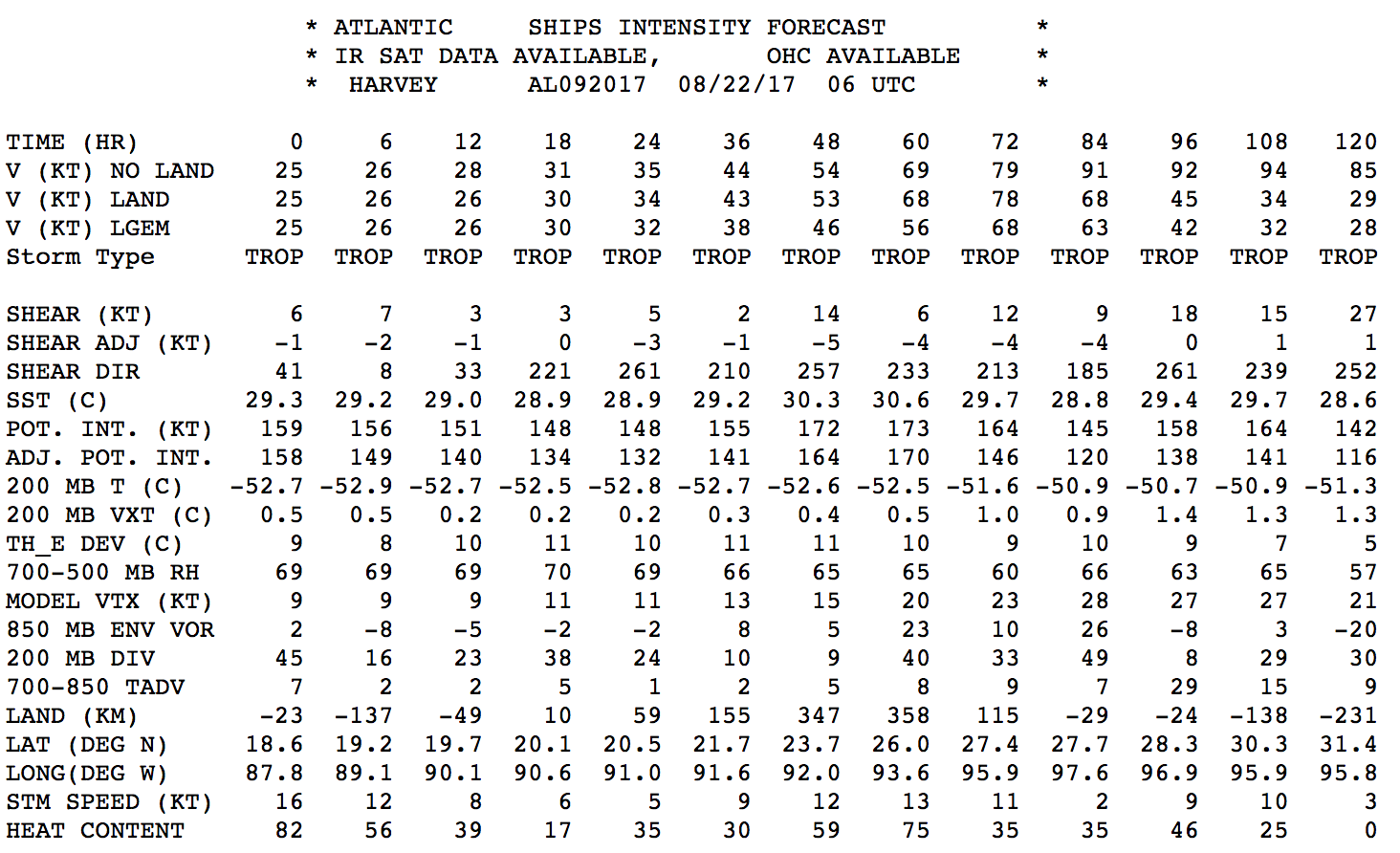

On August 22, just five days ago, Harvey was still a Tropical Wave. It was on the verge of re-organization. Most model guidance suggested it would be a Tropical Storm in 26 hours. And a Category 1 storm by landfall. A few outliers suggested a weak Category Two storm. Even the SHIPS Rapid Intensification Model showed “SHIPS Prob RI for 65kt/ 72hr RI threshold= 0% is 0.0 times sample mean ( 6.0%).”

So, I got on TV and said that this storm did not have the necessary ingredients to see rapid intensification with a hard turn toward South Mississippi. This wasn’t ground breaking information. The National Hurricane Center agreed. And would continue to agree for another 24 hours.

Some intensification was probable. But by August 25th at 10pm, Harvey was a Major Hurricane. Wind speeds nearly 86kts (100mph) faster than 72 hours earlier.

Incredible.

It was something no one could’ve seen coming three days prior. And those who claim they knew, aren’t being fully truthful or weren’t using science.

The Gulf of Mexico sea-surface temperatures were in the upper 80s and low 90s. That is a good 2C to 6C warmer than normal. The 26C isotherm was moderately deep, but not anomalously deep. The atmospheric conditions were ripe for development, sure, but with no anticipated anomalous catalyst for rapid intensification, the thought was it would strengthen, but be manageable.

But what happened between the 23rd and 24th was far from expectation on August 22nd.

By the evening of the 23rd, there was rumbling in the models that rapid intensification would be possible. That came SHIPS model showed “SHIPS Prob RI for 65kt/ 72hr RI threshold= 52% is 8.7 times sample mean ( 6.0%)” a much higher number than 24 hours prior.

Overnight from the 23rd to the 24th, an explosion of very strong nocturnal convection was the anomalous catalyst needed. And while I’m not Tropical Meteorology expert, I would surmise that when the storms fired up overnight, moving north, the storms dropped the air pressure of the center of circulation behind them. That lowering of pressure helped quicken organization and allowed for the development of more storms. That, coupled with the very warm sea-surface temperatures and moderately deep 26C isotherm offered a good foundation to begin rapid intensification.

An analogy might be that dumping a can of gasoline on the ground with matchsticks laying everywhere might not be problematic. But when you light one, the entire area is going to ignite. The sea-surface temps, 26C isotherm and atmospheric conditions – even added together – may not have been enough. But when you had a bunch of storms fire up overnight and shift Harvey north a bit, dropping the pressure, you just – in essence – lit a match over a ground covered in gasoline.

Again, I’m not expert in Tropical Meteorology, that is just an observation with an educated guess. I am very interested to see what the researchers learn from this storm.

But, back to the intensification, what was the chance that happened? Very small? But there was still a chance. And I didn’t say that. I didn’t give the normal best-case worst-case. Now, people are looking at me saying it was a “bad forecast” on August 22nd for August 25th.

Back to the Messaging with Some Dichotomy

This was a “bad forecast” that – at three days out – accurately depicted the forecast track, main threat of the storm for Mississippi, and the timeline of events: Harvey is moving toward Texas, It would bring the possibility of flooding to South Mississippi, and it wouldn’t happen until next week.

All of those things happened. All of those things are true.

But because I said it wouldn’t be like Katrina, rapidly intensifying and hooking toward South Mississippi, the message received was “It won’t be like Katrina.”

It was a bad forecast because perception, in this case, is reality.

This is why: I have learned, this is how a lot of people classify Katrina…

- It got into the Gulf, no one saw that coming

- It turned randomly, no one saw that coming

- It got really strong, no one saw that coming

While none of those statements are necessarily true, that is the perception of a lot of people. So, when people remember “Nick said this wont be like Katrina” and then it does any one of those three things, my message is now invalidated. Bad forecast.

Complicating Things Further

There are a lot of things about tropical systems we don’t know. And can’t know, really, because the science is only so good. Each storm is different, too. Forecasting one while comparing it to another is not the greatest way to explain the impacts of a storm.

But, for humans (meteorologists included), our brains are wired to make comparisons when faced with data. Then we use our best judgement to make a decision.

That is why many people prepared for Katrina saying “It didn’t flood here during Camille, so it won’t flood now.” And stayed put. Camille was a big storm. A benchmark for the area. The data – to them – suggested that if the worst storm didn’t cause flooding, then this one wouldn’t either.

And then during Katrina, it flooded.

Why did it flood? Those are two different storms. With two different set of impacts.

But how does a meteorologist explain to people the impacts for one storm, without referencing another if that is how the human brain works? Well, I don’t know.

But, as a forecaster, getting on TV and comparing the two storms isn’t a great idea. Because – as shown above – unless you are clear and concise with messaging, and that message is repeated three times, most people won’t grasp the message completely. And that isn’t because people aren’t smart. It is because our brains are just not great at handling multiple abstract things simultaneously.

And that is why I’m more disappointed in my ability to communicate the real message: South Mississippi isn’t in danger.

Lessons Learned

Honestly, a couple things. One might be counter-intuitive.

First off, I think I’ve become too influenced by conversations and interactions with people. I spend as much time talking about what won’t happen on TV as I do what will happen. And this is because every time I chat with folks, they talk about what they read on social media or ask if the next storm will be like a benchmark storm from the past.

While it is important to address disinformation and ease people’s fears, those interactions may have permeated a bit too deeply into my narrative about tropical weather.

I will try to fix that by spending more time on what will happen making fewer comparisons to things in the past.

Secondly, I got a reminder that a clear message is most important. I can’t recall who said this, but it is a great piece of advice for meteorologists: A great forecast that no one can understand is a bad forecast.That happened to me.

Third, I’m pretty certain that this situation will be remembered in a similar way. “Nick said it won’t be like Katrina” will likely be used to discredit for future forecasts. And that’s disappointing for me. And for you. Because my goal is always to remain accurate with a clear message. The consequences of failing at either, mean failing at both.

Lastly, a quick peek behind the curtain for everyone (congrats, you read till the end!). I do this to help people. That’s it. Whether it is tornadoes, hurricanes, or just some clouds. I want to help people make it through their day prepared for whatever Mother Nature throws out. And most of the other meteorologists you know of are the same way. Plus, forecasting the weather is a humbling job. Very few in this industry are arrogant and/or condescending because Mother Nature knocks all of us down a peg. Often.

If you hear from people that I am – or any of your local meteorologists are – full of ourselves or talk down to others because we think we are so great, please ask them why they feel that way. And ask them to reach out to me or who ever they have a problem with. I bet they’ll find out we’re not so bad.