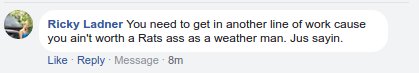

My life as a TV meteorologist was always interesting. The most interesting part was the viewer comments on facebook. Usually right before getting on the air, too.

Ricky, as it turns out, was upset. Ricky was anticipating rain. And didn’t get enough. Ricky would later apologize for the comment, saying “Please accept my apology it’s not your fault I didn’t get the rain I wanted today, again I’m sorry for being so rude Nick.”

No hard feelings! I get it.

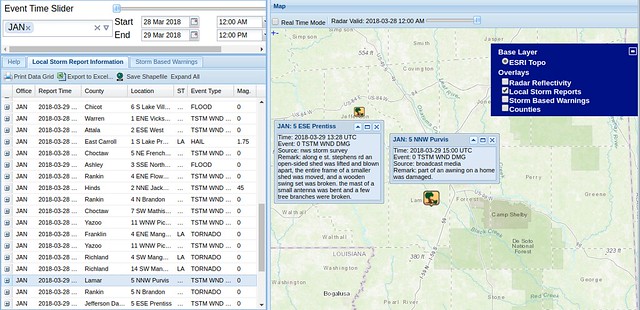

Because it does highlight a problem. The forecast called for the threat for severe weather, and two rounds of rain, one in the morning between 6a and 10a and another between 12p and 3p. The forecast was for 0.5″ to 1.5″ of rain – with a few spots seeing up to 2.0″ in total.

The severe weather didn’t occur (though, even that likelihood was discussed and was apart of the forecast). There were a few strong storms and some damage, but nothing technically severe. And the area picked up between 0.25″ and 2.0″ or rain.

To most meteorologists, this was a decent forecast.

But still, a viewer felt like the forecast was wrong for them. That is a problem – for everyone involved. And this is getting more prevalent. Not because forecasts are getting worse, either. In fact, forecasts are actually much better today than they have ever been.

So why do people feel like meteorologists are still getting it wrong? There are a lot of reasons. Part of the blame is on people and part of the blame is on meteorologists.

So, we are all to blame.

People want specifics

The desire for a more specific forecast is increasing. For every step meteorology makes as a science, the public is seeking information two steps ahead of that. People want to know more than there is a chance for rain. They want to know where the chance for rain is highest and when the rain will fall. How long will the rain last and how heavy will it fall. And how much will fall in total. And the information requested needs to be a short, quick, one-word (if possible) binary – 1 or 0 – answer. Either yes or no. One or zero.

Will it rain? When will it rain? How much will it rain? The actual answers to these questions are not straight-forward. But people don’t want probabilities. They don’t want a timeframe. They don’t want a range of possibilities.

People desire finite, binary answers. There will be rain. It will rain at 2pm. The rain will accumulate to 1.67 inches.

But the science of meteorology isn’t designed to give those answers. The science and the math are designed to give probabilities and a range to likelihoods.

What Brad is showing in his post is where meteorology excels: probabilities and percentages.

Let’s make an analogy using one of my favorite sports – Baseball.

Historically, if you hit with above a .275 batting average, you are probably considered a “good” hitter. So if we took the top 26 batters in the MLB from this past year and assigned them a letter, what is the percent-chance that if you pick a letter, it will correspond to a better with better than a .275 average?

If we run the numbers, there is an 80-percent chance.

That means, there is a 20-percent chance that when you select, you pick Andrew Vaughn (.271) and not Bo Bichette (.290).

Same thing goes with a percent chance for rain. We can call for an 80-percent chance. But that still means you could be dry.

Every person’s threshold is different

But maybe that 20-percent chance isn’t a big deal to you. While to someone else, it is huge. That si a problem. A 20-percent chance for rain to one person may mean something different than to another. One may cancel a picnic at 20 percent. Another may still go golfing. If it rains on the golf, but not on the picnicker… That was a bad forecast to both people. Even if it was actually accurate.

A 20 percent chance of something happening can be a very abstract concept for a lot of people. The world to most people is logical and linear. So they seek out binary answers.

Meteorology isn’t binary

In response to the request for binary answers, some meteorologists over-promise on the forecasting ability of the science of meteorology. It happens occasionally at some television stations, many youtubers, and quite often with rogue facebook pages.

Offering to tell people days in advance when the weather will get to their house specifically is a bit of a stretch given the accuracy of the science.

“How much snow will you see on your patio? Tune in tonight at ten and we’ll track the snowfall, giving you the exact total you’ll wake up to in the morning.”

The example above is one of a million. I see it all the time. As the kids say, “very cringe.”

I will say, though, that telling folks “I know how much snow will be at your house” is an effective way to get people to tune in to the news. Because that is exactly what people want to know. Will it? When will it? How much will it?

But can anyone even know those answers? Oh sure, a computer model can kick out some data points. But is that accurate to the ability of the science?

I would argue no. And I think a lot of actual scientists – after reflection – would probably agree. For many reasons.

And maybe I’m being unfair to WUSA above. I know Chester. He is a GREAT meteorologist. Maybe on TV they discussed ranges and didn’t give any specifics. But when you break it down to neighborhood level, you are opening the door for trouble.

Even if a meteorologist says, “Smithville, our computer model says you’ll see 2.75 inches or snow by the time you wake up.” and there is 2 inches at one house and 3.5 inches at another – that is a bad forecast. Too little for one person and too much for another.

Even if the average between the two houses is – in fact – 2.75 inches, it is still a bad forecast.

Recently, during a snow event in Louisville, Kentucky, I watched weathercast after weathercast leading up to an event where these meteorologists spent a lot of time spelling out how much snow people would see… completely missing the bigger problem. There were going to be 40mph winds with the snow. So any snow that fell was not going to fall evenly and would not be easily measurable.

Against the side of houses you’d have 9 inches and in driveways you’d have bare pavement.

I’m using Kevin as an example here because I know him and like him. And I think he does a good job. He hit on the major points – rain to snow, then flash freeze, then cold temps. It is a good graphic.

But I watched him for a few days with very little mention that there was going to be no way for the Average Joe to accurately measure the snow and the totals were going to be dictated by your location relative the the wind blowing.

So, the people got what they wanted from a forecast, but were left open to being soured after the event when the totals weren’t as “predicted” due to the lack of accurate measurements.

So, we really are shooting ourselves in the foot with this stuff.

Weather data is free, but you get what you pay for

No one in the public knows where weather information comes from anymore. I’ve talked about this before. Probably too much. No really, at nauseam. “they’re saying…” is one of my trigger phrases.

It used to be that a weather forecast came from the National Weather Service, a local television weather person or The Weather Channel. And most of the time, before 1980, the forecast was most likely actually prepared by the NWS. For the last 40 years there has been a diversification of who is creating what in the weather forecasting world. But all of the different pieces of the “weather community” were basically the same thing in the public’s eye.

But today, anyone has access to forecast data and can create their own forecast. Any person can start their own website and produce slick weather graphics. Anyone can share something a million times on social media.

Who cares? Big deal, right?

Well, sort of. The forecasting part isn’t even the biggest problem. The problem is that the public – perhaps, even you reading this? – still doesn’t know the difference between an anchor on TV giving a forecast, a degreed meteorologist on television, a meteorologist at the National Weather Service and a weather enthusiast with a home office and an internet connection.

And that isn’t their fault. Why should they?

But sometimes the enthusiast with an internet connection can come up with some doozy forecasts.

When those crazy weather forecasts for big blizzards, huge hurricanes, and fantastic heat waves don’t come to fruition… guess who pays the price? Everyone in the weather community. Because folks in the public, generally, don’t know the difference between legitimate forecasting and people throwing spaghetti against a cabinet.

But even the fake forecasts aren’t the biggest hurdle. The biggest hurdle for the public’s understanding of their own consumption of weather forecasts is their phone. The stock weather app with most phones is ‘grip and rip’ (if I can borrow a line from John Daly) data turned into a forecast. With no – or very limited – human quality control.

And it offers information, claiming super localized and specific detail which it doesn’t actually have.

So people can pick up their phone and tap the “Weather” app, get a forecast and go. It is incredibly convenient. And incredibly inaccurate.

But – going back to an earlier point – most people don’t know where that information comes from.

And again, why should they?

Sure, now you know that most weather app information is “Grip-and-Rip” data. But people don’t know that is isn’t vetted by the local television meteorologist, nor the local National Weather Service office, nor the click-baiting weather enthusiast’s facebook page. So the person who grabs that forecast, gets bad information, and is ultimately disappointed with the outcome, blames whomever they choose.

Usually everyone offering a weather forecast. And now they can do it more publicly than ever.

People broadcast the disappointment because social media allows them a place to voice their frustration. This is pretty straight-forward. The blame people want to aim at the phone is instead aimed at local meteorologists – for something they have no control over. So, whether it is the click-baiting enthusiast or a stock phone app, the local meteorologist generally gets the blame.

Meteorologists will never be perfect

Meteorologists forecasts are getting so good, that the public expects perfection. But forecasts aren’t perfect and never will be. In general, the statistics I kept for the forecast for the next day hit around 93-percent accurate. Down to 87 percent for two days out. About 82-percent three days out. And about 75-percent at five days. And around 70-percent 7 days out.

I do a 14 day forecast and stats show it to be a bit over 55 percent on Day 14 when within five degrees and 20-percent chance for rain. Not great.

But this is a big deal. Flipping those numbers on their head and you get something a bit different…

That also means there will be seven times per season that a great meteorologist will miss the forecast 24 hours out.

It will happen. And it drives the meteorologist more crazy than you can even imagine. A meteorologist is likely more upset than the public.

But that doesn’t mean that the other 83 days a forecast isn’t worth attention. Nor does it mean meteorologists are paid to be wrong.

The problem is the type of forecast the public now desires and what meteorologists can actually provide are two different things.

So, despite the meteorologists making headway on producing a better forecast, because that forecast isn’t binary, it doesn’t resonate with most people and it is – thus – a worse forecast.

The solution?

The solution is the million-dollar idea.

Playing along with The Dude above, I’ve always thought that education was the solution. If more people were raised / taught in school what a percent-chance for rain really means, it would be most helpful. To both people and meteorologists.

Perhaps along the same vein, it might be useful for people to recognize their own personal thresholds for weather. Figure out what an inch of snow means for them. Figure out what a 60-percent chance for rain means for their plans.

And meteorologists need to improve their communication of a forecast. And they need to stop over-promising on forecast information they can’t actually offer. Neighborhood snowfall totals 24 (or more) hours out, specific rainfall totals, top wind gusts, etc. Meteorology is built to offer probabilities because it is built on math and statistics.

But ultimately, I don’t have the answers.

As I posted above. This is all just, like, my opinion, man.