As a surface feature moves north out of the Gulf of Mexico and across Texas, a warm front with usher in moist air and destabilize the atmosphere enough for showers and storms across east Texas, sections of Louisiana and Mississippi.

the threat for severe weather is low, but not zero. But it looks like things will have to wait until later this afternoon before they get going.

The Setup

As an upper-level low sags out of Arizona and into Mexico, the atmosphere will be modestly “opened up” ahead of it. At the same time, the warm front that is currently across the Gulf will ease north through the day in response the a surface low. Though, it will likely take until the evening and overnight hours for it to begin to affect Louisiana and Texas weather. As it does so, the influx of warm moist air will help to destabilize and the atmosphere from the surface. This will allow surface-based showers and thunderstorms to develop. These will have the possibility of strong winds and isolated tornadoes.

In Detail

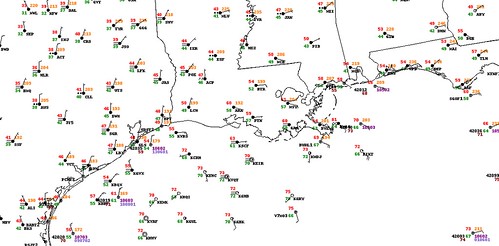

Here is a look at the recorded surface observations from 12z this morning.

Notice that all of the barbs on the map are – generally – from either the east or northeast across the area. That means as of 7am this morning that the warm from was still in the Gulf. We know that because winds behind a warm from are coming from the south, southwest, or southeast. There are a few barbs on the surface map that show wind from one of those directions, but they are well into the Gulf.

And as of this writing, the warm front hasn’t moved much. That means that all of the convection (thunderstorms) will be based off instability from aloft, rather than from the surface. That is because the wind is blowing at different directions, and at different speeds throughout the atmosphere. You can have warm moist air above you, but be cooler at the surface and still see a thunderstorm.

Here is a look at the 10:30am Radar from the National Weather Service.

As of this writing there isn’t much thunderstorm activity to speak of. In fact, there likely is only one or two rumbles of thunder on this map and they are likely along the Louisiana/Mississippi border.

For the most part, as of 10:30am, there isn’t much to speak of.

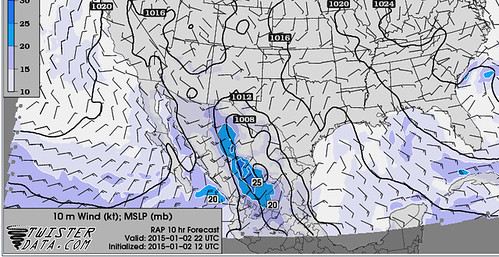

This will change as we head through the afternoon. Here is a look at the RAP computer weather model. This is one of our shorter range models that does a decent job handling frontal progressions. Notice by 22z – or about mid-afternoon – the barbs have flipped around to the south or southeast along the coast of Texas, Louisiana, and Mississippi. That is the warm front moving north. Places that have barbs pointed to the southeast will start to see warmer, moist air move into the lower levels of the atmosphere. That will promote a destabilization of the atmosphere from the surface. It will allow for surface-based thunderstorms to develop.

As an aside, it is important to note the difference between “allow” and “begin” to develop in respect to these surface-based thunderstorms. Allowing storms to develop doesn’t guarantee development. It just means that the atmosphere will be more conducive and better-able to support thunderstorms. It doesn’t mean that they will begin to develop at that point.

You can see the instability on the rise from the RAP computer weather model, too. Here is a look at the surface based CAPE.

Notice that the highest instability according to this model will be across eastern Louisiana and southern Mississippi.

But, that isn’t all you need to make a stronger/severe super-cellular thunderstorm. You need a rotating updraft, too. And for that, you need wind speed and/or direction to change with altitude. Meteorologists generally call that wind shear. But often in the south during the cold season, there is plenty of wind shear for severe weather. So instead, here is a look at helicity.

From Jeff Haby: Helicity (HEL) is a mathematical quantity derived from: 1. speed shear (how much wind speed increases with height) between the surface and 3 km above, 2. directional shear (how much wind speed changes direction with height) between the surface and 3 km above, 3. The strength of the low level wind directly into the speed and directional wind shear. The stronger each of these components is the higher the helicity.

In this discussion, you are looking at the 0-1km HEL values instead of the 0-3km values that Haby (who, frankly, is awesome) talks about here. Often you want helicity values along the Gulf of Mexico up over 200 for a storm to grow into a severe storm. Often if a storm is in an environment with helicity values over 350 it can be tornadic.

But notice that the area with the highest CAPE (next above) has the lowest helicity (above). So the forecast isn’t cut-and-dry for this afternoon and evening in terms of surface-based severe thunderstorms. The development of a severe storm will likely be along the boundary of the area with the most CAPE and the area with the highest helicity.

That, along with other reasons, is why the Storm Prediction Center has issued a “Marginal” risk for severe weather near the boundary of those two parameters. Because that is where the low-level flow will be moist, the atmosphere will be destabilizing, there is sufficient turning with altitude and the instability will be surface based.