I received a good question on Twitter that I couldn’t answer it quickly and easily – and with the allotted number of characters – so I wanted to take some time to answer it here. As best I can. When it comes to Monsoon Gyre’s I am far from an expert. However, I will do my best to translate what the expert research shows into some digestible English.

There is a bit to unpack here, but it is a good question. Cody is asking about the difference between an AEW, or an African Easterly Wave, and a CAG, a Central American Gyre. A lot of times in the discussions that the National Hurricane Center puts out they’ll mention things like gyres and troughs or waves and clusters.

And, again, for full disclosure: I’m not a tropical meteorology expert. While I try to do a lot of reading and researching of tropical meteorology, I leave a lot of this stuff to the research pros. Because this stuff is tough. So, I’ll do my best to break this all down, but again, I’m not the subject-matter expert.

Consulting the experts

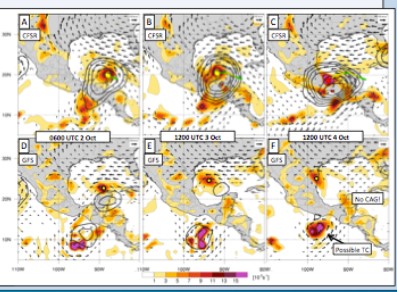

If you want to read more about this type of stuff, Twitter is a great place to be. There are a host of tropical meteorology experts there. One of which is a Central American Gyre expert, Philippe Papin. He took some time to break down the Central American Gyre relative to a potential system.

There was a lot there, and maybe some stuff you didn’t quite follow (and that’s okay!). So lets take a step back for a second… how do we differentiate between the two? A great question!

Breaking it Down

According to the American Meteorological Society Glossary a Monsoon Gyre is…

A convection of the summer monsoon circulation of the western North Pacific characterized by 1) a very large nearly circular low-level cyclonic vortex (not the result of the expanding wind field of a preexisting monsoon depression or tropical cyclone) that has an outermost closed isobar with a diameter on the order of 1200 n mi (2500 km); 2) a cloud band bordering the southern through eastern periphery of the vortex/surface low; and 3) a relatively long (two week) life span.

Initially, a subsequent regime exists in its core and western and northwestern quadrants with light winds and scattered low cumulus clouds; later, the area within the outer closed isobar may fill with deep convective cloud and become a isobar or tropical cyclone. Note: a series of midget tropical cyclones may emerge from the “head” or leading edge of the peripheral tropical cyclone of a monsoon gyre.

But Central American Gyres are a bit different. According to Phillipe Papin, a CAG is…

Central American gyres (CAGs) are large, low-level, cyclonic circulations that are observed over Central America during the tropical cyclone (TC) season. CAGs often occur in conjunction with TCs, and can result in torrential rainfall over portions of Central America, the Caribbean Islands, and eastern United States.

Papin did an entire Master’s Thesis on CAGs.

Want more info? Here is a video of a presentation he gave on this topic!

Okay, but what about African Easterly Waves? Let’s go back to the American Meteorological Society Glossary…

A tropical easterly wave that is generated due to a combined baroclinic and barotropic instability of the African jet. African easterly waves have a period of three to four days, a horizontal wavelength of 2000-2500 km, and maximum amplitude in the lower troposphere. An average of 60 African easterly waves form between May and October while large-scale environmental conditions favor the existence of the African jet. African easterly waves may propagate westward across the tropical and subtropical North Atlantic and may reach the Caribbean Sea and western North Atlantic. Some African easterly waves become hurricanes.

Putting it Back Together

Let’s loop back and talk about what these two things are…

CAGs…:

– Large-scale, broad, low-level circulations

– Often located in one area

– Can eventually spawn/become Tropical Cyclones

AEWs…:

– Localized to small-scale, clusters of storms

– Move from Africa toward Latin America

– Can become Tropical Cyclones

The differences are mainly in the placement and size. The CAGs tend to be broader while the AEW are a bit smaller and more localized (though still pretty big). The CAG is located near Central America while AEW come from, well, Africa. Both are related to tropical cyclones. The CAG can spawn tropical systems while AEW become tropical systems.

Do CAGs make bad hurricanes?

It is tough to define a “Bad” hurricane as all of them are potentially bad. But, they can produce hurricanes, yes. From the research I’ve read most of the Tropical Storms and Hurricanes that are birthed from the CAG are weaker and one-sided than storms that develop from AEWs. The main concerns from tropical systems that develop from the CAG are flooding rains and storm surge – and not usually the wind. So for these types of storms it is important to focus on those impacts, and not the category.

In fact, as of this writing, two of the last three tropical systems that have affected South Mississippi came from the CAG. Hurricane Nate in 2017 and Subtropical Storm Alberto in early 2018 were both born out of the CAG.

You may recall that both Nate and Alberto were pretty one-sided and brought South Mississippi a lot of rain and some storm surge. But not much wind. In both cases, though, the center of the storm was to the east of (most of) the area as it passed through. That put South Mississippi on the western – and weaker – side of both storms.

That said, Hurricane Michael also formed from the CAG. And that was a powerful Category 5 Hurricane. So, further research is needed on the tropic to decipher if Michael was the ‘rogue wave’ of hurricanes from the CAG or if stronger hurricanes can form from the CAG.