1/5/20 UPDATE:

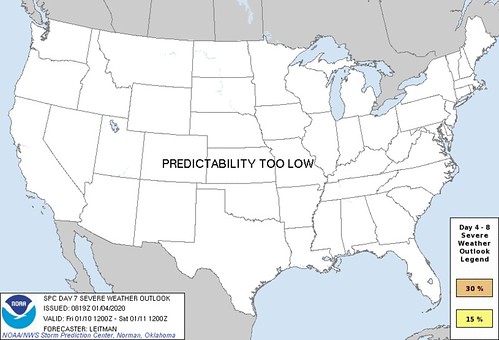

The SPC has now included parts of the Gulf Coast under a Slight Risk for severe weather for Friday and Saturday. For more information, head here. On that page, you can scroll down a bit and see that the SPC has highlighted parts of Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Mississippi, Alabama and the Florida panhandle as areas to watch for severe weather. Plus there is a brief discussion from the SPC below the maps to explain the overall setup.

ORIGINAL:

It’s like The South doesn’t know how to do Winter like the rest of the country or something. Everywhere else it is cold or snowy. Down here, we’re still getting storms like it is April. Anyway… Here is a quick casual peek at some early data about the storms coming this next weekend.

Fir thing is first, please know that this isn’t the “final” or “end-all-be-all” to the forecast. A lot will change between now and then. This is just a bit of interrogating some data to see what we can pull from it.

Two options playing out

Right now, between the model data available, there are two different outcomes painted by the data. Both bring the Gulf Coast – from the western Louisiana coast to the Florida Panhandle – a chance for storms and the potential for severe weather. One offers a better chance for more significant severe weather for the region. The other shifts that threat north into the Tennessee Valley.

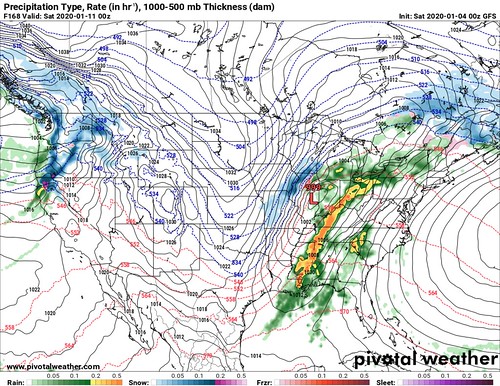

The GFS

The GFS computer model data suggests a potent cold front swings through late Friday and into Saturday morning. This would offer a quick burst of storm activity along the front with the potential for heavy rain, frequent lightning, some pretty strong wind (up to 70mph), decent-sized hail (up to the size of quarters) and the potential for a tornado or two.

Current data, as well as the data over the past few runs, suggests that if this were to play out the storms would be mainly along the front. With little to no storms ahead of the line. While the resolution (the ability to see smaller details) of the model probably isn’t high enough to pick out individual supercells ahead of the line, the data doesn’t show an atmosphere conducive to the development of such storms.

REMINDER: Supercells are the lone storms that tend to produce the more significant severe weather. The December tornadoes that moved through Columbia, Sumrall and Laurel were all spawned by a single supercell storm

The GFS brings the storms through on Friday night through Saturday morning. One quick punch in the gut, and then it moves out.

The ECMWF

The European model is a bit different. Instead of a quick shot to the gut, it is a bit slower with the movement of the next system. That allows more time to condition the atmosphere for severe weather. This scenario would allow for showers and storms to develop along the front as it passes, but also ahead of the front before it arrives. The same threats apply in this scenario. The potential for heavy rain, frequent lightning, some pretty strong wind (up to 70mph), decent-sized hail (up to the size of quarters) and the potential for a tornado or two.

Those storms ahead of the front could be as innocuous as instability showers and as organized as supercells.

In this case, There would still be rain on Friday. But it may be an afternoon, evening, overnight rain. There may be a few stronger storms, too. But severe weather would be unlikely on Friday. Then on Saturday, more hit and miss showers during the daty and into the evening.

But overnight Saturday and into Sunday morning early, the front would move through with a chance for severe storms along the front and potentially severe storms out ahead of the front.

Some nerdy details worth noting

While the outcome seems pretty close to the same (Showers, storms, severe weather possible), the difference between the two models is pretty drastic at the nuts-and-bolts level.

between the models

The GFS keeps this next system as a regular trough at 500mb, with the surface low near Indianapolis as the front slides through.

The Euro cuts off the low, and “stacks” the 500mb Low on top of the surface Low around Kansas City as the front passes through.

What does that mean for the final forecast? Maybe nothing. Maybe everything? This whole setup is still a long way out, so none of these specifics may matter for the final forecast.

But, all things being equal, the GFS trough-with-the-low-near-Indy event would probably be less potent overall. It would still allow a line of potential severe storms to move through the area, it just may be a bit more tame overall.

The Euro-cutoff-low-=that-is-stacked would probably provide a more potent setup, but it would be more potent for places other than the Gulf Coast. Likely further North toward and into the Tennessee Valley.

The Analogs

The CIPS Analogs show a pretty decent glimpse at the potential outcome once you go under the hood. At face value, nothing stick out. But once you look at the projections and take it another two or three steps, it is possible to see what evolution it is highlighting as more likely.

The CIPS shows that historically, a setup like this tends to evolve with more rainfall to the north of the Gulf Coast. It points that the heaviest rainfall occurs in the Tennessee and Ohio River valleys and back toward the Mississippi River near Memphis. This would suggest rain along a warm front passage, followed by more rain along a cold front as it passed through. BEcause if it were just one or another, it wouldn’t be the ‘highest’ total. In order to get the highest, you usually need two frontal passages – warm and cold.

Okay, so if it suggests that historically setups like this have a warm front as far north as the Ohio River, that means a pretty large surge of air moving north. The CIPS also shows that historically, nearly 80-percent of the time parts of Kentucky get into the 60s with this kind of a setup.

Stay with me here! So, we have temperatures in the 60s as far north as Kentucky (south side of the Ohio River) and the Ohio River Valley and Tennessee River Valley receiving the most rainfall. So, we can back out of this data that severe weather is more likely from that point south due to the rich available moisture and uncontaminated environment. In other words, generally, areas south of the heaviest rain estimates and along the trough axis tend to be the areas where severe weather is most likely for any given potential setup (once specifics are available, those can be used, but for very general discussions, that rule tends to apply).

But how far south do we look? That is the million dollar question. I tend to ballpark it since I’m working with generalities at this point.

In this case, It would look like central Louisiana, southern Arkansas, central Mississippi and northern Alabama could be most likely to see severe weather – not the Gulf Coast.

So which one is right? What is the forecast

None of the data is “right” at this point. That, sadly, isn’t how weather forecasting works. If the data was ever “right” I’d likely be out of a job.

Please keep in mind that things will change. This discussion isn’t final. And the final outcome will likely be somewhere between these all of these forecast datasets. And the differences between the data, and how those differences evolve, are going to help us nail down which forecast data is more accurate as we get closer to this weekend. And eventually we will be able to offer an accurate forecast.

For now, please know that some time between Friday evening and Sunday morning there will be a chance for storms – some severe. The main concerns with this go-around are heavy rain, frequent lightning, gusty wind, small hail, and the potential for a tornado or two. The specifics will be shaken out in the coming days. And we will continue to keep tabs on the data.